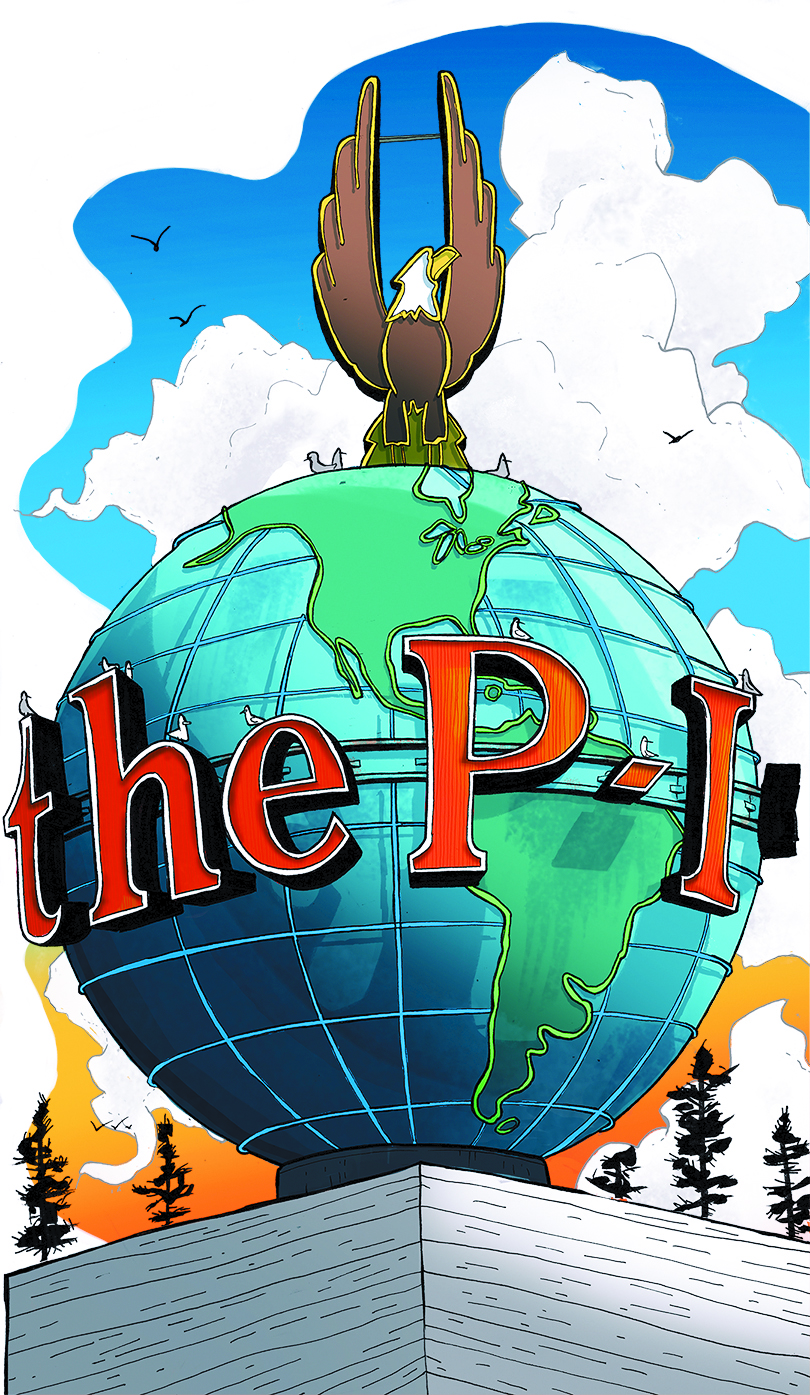

On March 16, 2009,the day before the Seattle Post-Intelligencer published its final edition, New York Times reporter Dan Barry put it just right: “For some, the Globe is the finest landmark in Seattle, surpassing even the Space Needle,” he wrote. “When aglow at night, it seems to float upon the cityscape, the continents highlighted in green against the dark blue, the motto—‘It’s in the P-I’—rotating in red letters five and eight feet high. A continuance is conveyed.”

When the mighty Hearst Corporation pulled the plug on the print edition of the 146-year-old paper and vacated its headquarters, no one knew what would become of the Globe, this 30-foot, 18.5-ton neon-lit marvel, forged from iron in 1948 at a cost of $25,932. Many wondered: Would there be a continuance for the city’s beloved beacon, topped by a majestic eagle, wings raised as if to take flight? Others worriedly theorized that Hearst might simply untether the Globe from its watchful perch overlooking Elliott Bay, crack apart its north and southern hemispheres, and cart the iconic monstrosity away in two massive pieces.

Happily, though, on March 7, 2012, the Globe was saved in a deal between Hearst and the Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI). Under the agreement, Hearst would continue ownership, but relinquish to MOHAI full control and rights to the Globe only after it was dislodged and set down in a new location—something the owners of the building at 101 Elliott Avenue, where the revolving rooftop spectacle has resided since 1986, have long insisted upon, and still do.

That same March afternoon, City Council members Jean Godden, Tim Burgess, and Sally Clark—all former journalists—gleefully announced that the city’s Landmarks Preservation Board planned to designate the Globe an official landmark the following month. Since then, April 2012, a long and plodding search by MOHAI and Hearst’s representatives has ensued to find the relic a new, permanent home.

There was talk, initially, that it be placed at the old Sand Point Naval Base hangar at Magnuson Park, or perhaps returned to its former place of glory at Sixth Avenue and Wall Street, site of the P-I building of yesteryear where the Globe was hoisted amid great fanfare on Nov. 9, 1948. Later other suggestions surfaced, such as displaying it inside the grand MOHAI building at South Lake Union, home to other famous signage, including the original Rainier Beer “R.” But the exhibit hall was not big enough.

Some of my old P-I cronies have joked that the Globe be barged out into Elliott Bay and ceremoniously sunk, a fitting metaphor for the steep decline of print journalism.

Still more ideas were batted about: the Olympic Sculpture Park; the southwest corner of South Lake Union Park; along the central downtown waterfront as part of the transformation project; or, in a more utilitarian vein, as a bright guiding (and spinning) light on a new Colman Dock ferry terminal. Crosscut writer Knute Berger reported in 2012 that the idea, however flippant, arose that the Globe be situated at the Highway 99 tunnel’s north portal. Also, Berger noted, “one wag at City Hall suggested that the Globe could be put to use as a pontoon on the new 520 bridge.”

Now, finally, three years after the Globe-saving deal, Seattle Weekly has learned that a strong consensus is emerging for the Globe to be relocated, restored, and resurrected in Myrtle Edwards Park.

MOHAI’s executive director Leonard Garfield, Councilmember Sally Clark, and Landmark Preservation Board Coordinator Erin Doherty have all confirmed that the 8.5-acre green space on the Elliott Bay shoreline may well inherit the Globe.

“We still have a ways to go, but yes, I feel like that’s the direction it is moving in,” Clark tells the Weekly.

Doherty said Hearst’s representative, Seattle land-use attorney Jack McCullough, briefed the Landmark board January 21 on the possibility of moving the Globe to the city-owned park named in honor of Myrtle Edwards, a City Council member in the 1960s and an ardent advocate of adding more parkland in Seattle.

Councilmember Clark says the likely location at Myrtle Edwards is just north of the Thomas Street pedestrian overpass, on the water side of the bike and jogging path that runs through the center of the park. A number of bureaucratic obstacles need to be cleared, adds Clark, one of them being that since the Globe would be within 100 feet of Elliott Bay, MOHAI and Hearst will need to secure a shoreline permit from the city. It is not clear how long that might take.

Garfield says a Myrtle Edwards site would meet MOHAI’s criteria for prospective locations: that it remain in the public landscape, be publicly accessible, and easy to view from many areas.

If all goes well, Hearst has committed to covering the cost of transporting the Globe to the park, while MOHAI will pick up the tab to have it fully restored—an estimated $200,000 to $300,000 (most of which would be generated by community fundraising activities)—and placed on a pedestal, its height yet to be determined.

“It will be illuminated and it will rotate again, and it will still say, ‘It’s in the P-I,’ ” says Garfield, who concedes that a lot of newcomers might wonder what in the world “P-I” stands for.

“The Globe is such a cool symbol,” elaborated Garfield in an interview last week at his MOHAI digs. “It almost has a Superman motif, a postwar symbol that Seattle was becoming a world city.”

A week before the presses went silent on that fateful March six years ago, the Post-Intelligencer offered its employees a “Last Visit to the Globe,”a trip to the roof to gaze upon the giant neon planet. Many staffers came, circled it, posed for pictures, and shed tears. For these P-I loyalists, the Globe was far more than a pleasant glowing orb in the night sky—it was a powerful presence that announced that their profession was noble, sacred, important.

The P-I Globe filled the front page on that final paper of March 17, 2009. Below the fold, the headline read: “You’ve meant the world to us.”

econklin@seattleweekly.com

Ellis E. Conklin worked at the Post-Intelligencer through the ’90s.