On its opening day this past spring, the line to get into the Bullitt Center stretched two city blocks.

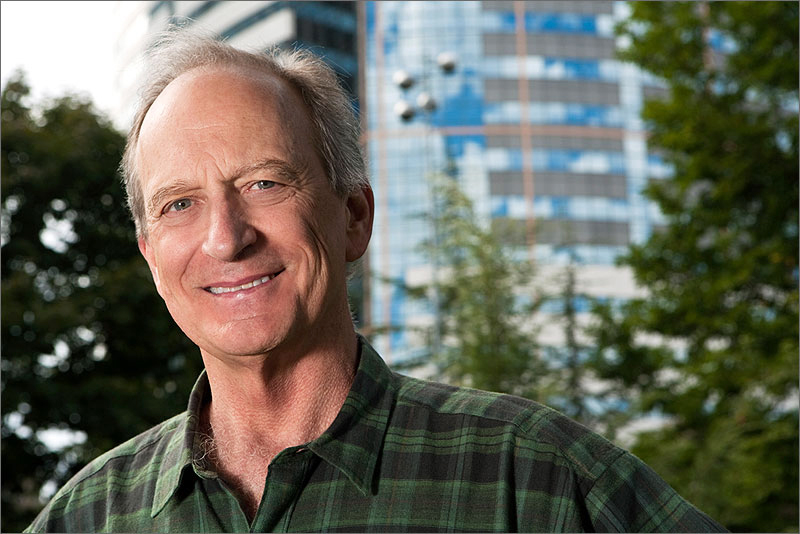

People weren’t lined up for a roller-coaster or a rock show—they were anxiously waiting to glimpse the inside of an office building. Denis Hayes was not surprised by the massive turnout—as the man who spearheaded the construction of the “Greenest Commercial Building in the World,” he knew he hadn’t just created a neat office building. He had created a palpable symbol.

“There is a real hunger out there for people to see practical, effective solutions that they can identify with and think that they’d like to be a part of,” Hayes says. “We still get about 20 to 25 people a day coming through for tours, and when they do we ask them ‘Would you rather go to work in the building you’re in now, or would you rather go to work in the Bullitt Center?’ The answer is always the same: ‘I’d rather be here.’ ”

The Bullitt Center is a gorgeously designed landmark of green architecture that sits at the top of Capitol Hill. Designed to mimic a living organism, the building is entirely self-sufficient and automated, producing all its own energy using massive solar panels on its roof—so much energy that Hayes set up a deal to sell the excess back to Seattle City Light. With the Bullitt Center’s opening, Hayes has helped established Washington as a leader in the national environmental effort.

But the Bullitt Center is only the most recent chapter in Hayes’ long, green-thumbed history. Most people know him best as the organizer of the very first Earth Day back in 1970, now celebrated in 180 countries across the world.

Growing up in Camas, Wash., Hayes first showed interest in environmental activism by contemplating his father’s work at the local paper mill, which “poured out totally uncontrolled pollution,” he recalls. “They poured out hydrogen sulfide and sulfur dioxide into the air that got into people’s lungs. They had huge fish kills for the stuff they poured out into the river. That was just seen as the smell of progress.”

Hayes would hike in the forested areas around his home, then come back a year later and find them a “moonscape” because of the deforestation his father’s work wrought.

After serving as the head of the U.S. government’s Solar Energy Research Institute, Hayes became unsatisfied with the slow, ineffective pace at which national policy was moving. He decided the best way to combat the situation was to focus on more regional efforts. During his time at Seattle’s Bullitt Foundation, that has been Hayes’ charge—making the Northwest the frontier of progressive environmentalism. “There’s almost an act of faith that if you focus on what you can do here, where you live, that it will have an influence around the world, and that they will simultaneously do it in their areas,” Hayes says.

Even with the Bullitt Center a success and Hayes’ regional focus seemingly paying off, there are still days when the weight of the global environmental issue weighs heavily upon him. “I was far more bleak and candid in my appraisal of all the stuff that was going wrong one night at a talk I was giving. I was of the opinion, you know, let’s just go to a desert island and drink ourselves silly because the world is hopeless,” Hayes says. “But then my wife, in her great wisdom, asked me, ‘Well, in Darwinian terms, what is the survival value of hopelessness?’ ”

Hayes laughs. “You know, you’ve just got to adapt the attitude . . . you know, the belief that there is some solution to this.”

That’s why the Bullitt Center seems to be attracting the curiosity of so many ordinary people. It’s a real, tangible solution to our world’s problems. And it happens to sit right in the middle of Seattle.

ksears@seattleweekly.com