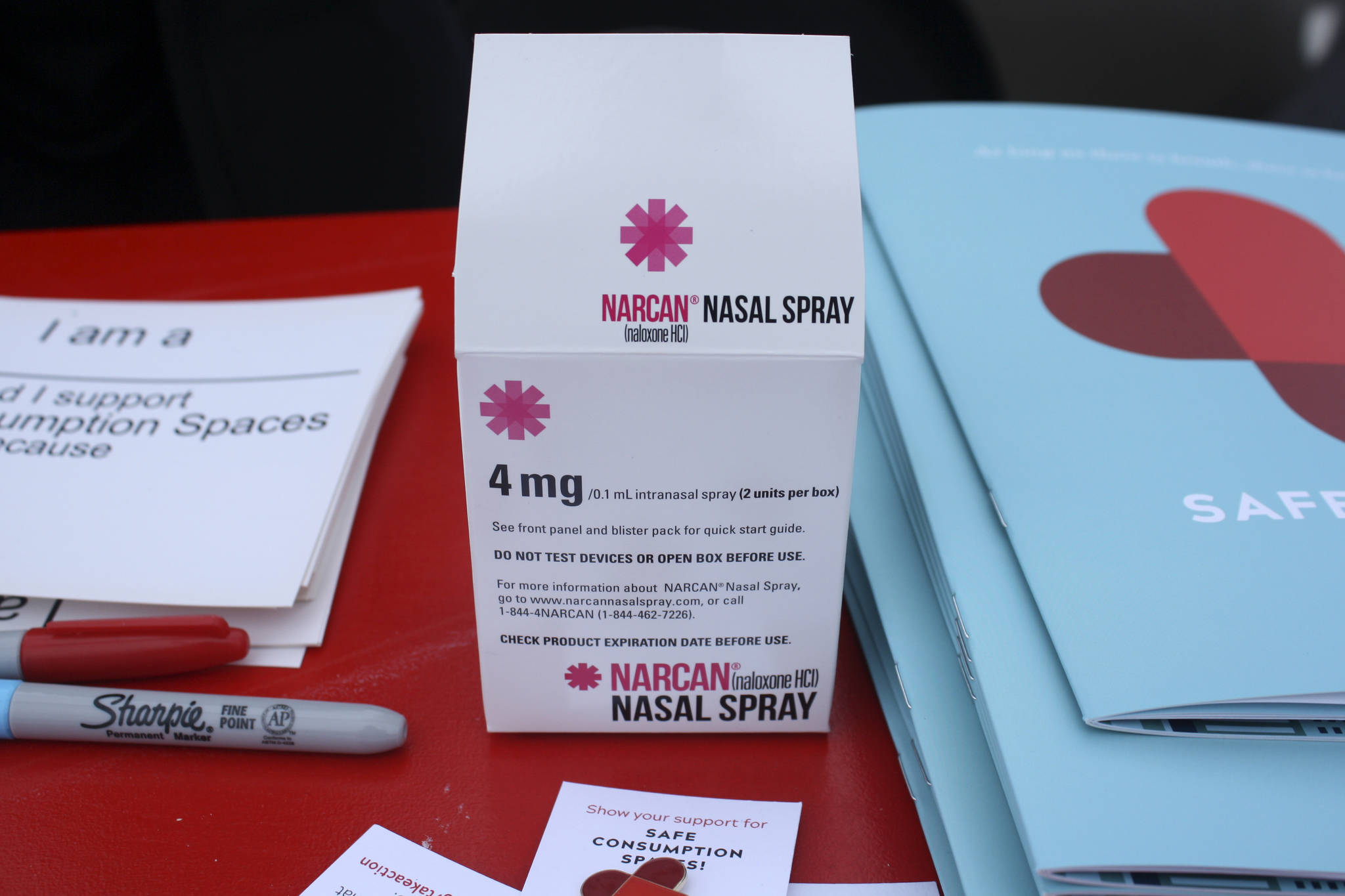

As people sleepily began their Wednesday morning commutes with coffee cups in tow, registered nurse Mandy Sladky and five other health care workers set up a public information booth near the entrance of the Capitol Hill light rail station. Informational packets about safe consumption spaces (SCS)—medically-supervised facilities where intravenous drug users are provided sterile injection materials—and a bottle of the opioid antagonistic naloxone were piled on a red table underneath a poster bearing the words: “Ask me, a nurse, about SCS!”

Sladky wore a purple stethoscope wrapped around her neck and a black shirt that read, “Safer is Better.” Throughout the morning, she and five other volunteers fielded questions from passersbys who didn’t know what SCS were, or who wanted to voice their support for the sites. Some commuters approached the table to ask questions while also grabbing one of the chocolate donuts that had been laid out. When one man asked Sladky whether the sites would increase drug use in those areas, she launched into a five minute conversation in which she pointed to studies conducted in Vancouver, British Columbia—which has had a SCS since 2003—showing that sites save the criminal justice and public health systems money while increasing public safety.

“They connect people to services, which gives them access to treatment, so it actually lessens drug use,” explained Sladky, “it certainly lessens outdoor public use—and therefore discarding syringes in places like alleyways and parks. And crime does not increase in the areas.”

Wednesday’s information sessions were hosted by the Health Care Workers for Safe Consumption Spaces, a group of nurses and other medical professionals who support safe consumption sites. Health Care Workers for Safe Consumption Spaces was co-founded by Sladky in 2016, and has since joined a coalition of other advocates in the local Yes to SCS campaign. Healthcare workers also took morning and afternoon shifts at the Beacon Hill and University of Washington light rail stations to discuss the benefits of safe sites and to dispel misconceptions.

The event comes on the heels of county-wide efforts to address the opioid epidemic. Safe-injection sites were one of several addiction prevention recommendations endorsed by experts in the Heroin and Prescription Opiate Addiction Task Force convened by Renton, Seattle, and Auburn mayors in 2016. Last January, former Mayor Ed Murray and County Executive Dow Constantine announced that Seattle and King County would create one safe consumption space in Seattle and one outside of city limits. Then in November 2017, the Seattle City Council included $1.3 million in the 2018 budget for the creation of a site.

But Sladky and other safe-injection site advocates worry that the process will continue to be held up by bureaucratic processes. She wants to ensure that the city’s promise to create spaces for people to safely consume drugs and get resources to help them with their addiction stays at the forefront of the public’s mind. “The longer it takes to get these sites up and running, the more people that are dying. As healthcare workers, we just can’t sit by idly and let that happen,” Sladky said. “We have an obligation to our patients and to our community to start saving lives as soon as possible.”

Safe consumption sites have faced a lot of local pushback over the past year. Last summer, opposition groups gathered over 47,000 signatures for Initiative 27, a February ballot measure that would have placed a ban on sites in King County. However, King County Superior Court Judge Veronica Alicea-Galván struck the measure from the ballot in October, ruling that it would impede the work of public health officials. Yet, several cities in King County including Federal Way, Bellevue, Kent, and Renton have already banned the facilities.

Seattle is currently conducting a feasibility study that will include operational costs for various facility options, community engagement plans, and criteria for selecting sites. In an email to Seattle Weekly, Human Services Department spokesperson Meg Olberding said that the study is expected to be completed this month, but that the city anticipates planning and community engagement to continue through the summer before a site is chosen and becomes operational.

Yet she points out that the sites are one of the county’s many efforts to address the opioid epidemic. “Recently, we’ve worked with partners to open a new detox and treatment facility. We’ve also started a pilot project that offers rapid access to buprenorphine to treat opiate use disorder. We continue to focus on prevention by providing naloxone kits (over 1,500 distributed to law enforcement and treatment providers) and access to secure medicine drop boxes,” said Olberding.

Although Seattle announced early last year that it would be the first in the nation to create safe-injection sites, the prolonged planning process may end up making Seattle the third. On Tuesday, San Francisco officials voted to open two safe consumption sites this summer, just three weeks after Philadelphia announced it would open one within the next six to 18 months.

More than anything, the Yes to SCS campaign contends that safe consumption sites will save lives. Patricia Sully, a Public Defender Association staff attorney who helped spearhead the campaign in 2016, said that one of her clients was a recovering drug user who withdrew from her support network and healthcare providers when she relapsed because she was ashamed. “One of the reasons why she really talked about a safe consumption space being important was because it would be a place where … she knew she would be loved and accepted even if she had relapsed and she could get the help she needed to get connected back to treatment when she was ready,” Sully said.

Sladky agrees. During the morning informational session in Capitol Hill, she spoke with one person who shared that his friend had just overdosed and died this week. “He was really happy that we were here and was obviously clearly emotionally affected by it,” she said. “And I think those are the kind of people we want to reach.”