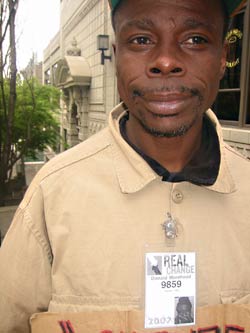

On a Tuesday afternoon at the University District Safeway, Edward McClain’s booming voice can be heard from almost a block away. “Real Change,” McClain says to every passer-by in a rising tone. “Have a nice day.”

The most famous hawker of Real Change, Seattle’s street newspaper, McClain has been a fixture for 12 years at the Safeway, where he consistently sells between 1,500 and 2,000 papers each month. Like all vendors, McClain buys his papers for 35 cents and sells them for a $1 “donation.” (Vendors keep all profits from each paper sold.)

But unlike other vendors, McClain is so successful that he’s been able to keep an apartment for the past 10 years; his Real Change income pays the rent and utilities for his one-bedroom apartment in Lake City. “Everything you have in your house, I have in mine,” he says with pride.

Though many Real Change buyers assume the paper is sold by the homeless, anyone can be a Real Change vendor. One simply must walk into the newspaper’s Belltown office, sign an agreement to abide by the vendor code of conduct, and sit through a one-hour orientation, after which the newly minted vendor receives a starter set of 10 free copies of the paper. Real Change isn’t alone in allowing all comers to become vendors. None of the main street newspapers in Portland, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C., checks the income or housing status of prospective vendors. Nor do they retire vendors once they’ve bootstrapped their way out of homelessness.

At the Safeway, McClain, 64, sells a paper every few minutes. When Abara Ijiomah exits the store, he makes a beeline to McClain and buys a paper. Ijiomah, 23, says he buys a paper just about every other week, though he admits he doesn’t read it. “I buy more to contribute than to read,” he says, chuckling.

Ijiomah says he didn’t know that McClain had his own apartment, or that there were no requirements to become a Real Change vendor. “That puts a little different spin on it,” he says. “The money should be going to help people find housing and cover medical costs. It shouldn’t be a resource for someone who’s looking not to have a 9 to 5.”

In truth, no one becomes Warren Buffett by selling street newspapers. “We don’t have rich corporate attorneys selling the paper,” laughs Laura Osuri, executive director of Washington, D.C.’s Street Sense. “It’s really not an issue. It’s usually always people who are homeless or close to it.”

Real Change employs roughly 250 vendors, who the paper claims are “the poor and homeless of Seattle.” “We don’t have to means test to know that we’re serving poor people, because it’s fucking obvious,” says Tim Harris, executive director of Real Change. (This is apparently a sensitive subject for Harris, who, before this story was even written, wrote an 833-word blog rant entitled “Seattle Weekly: What the Fuck?” Harris’ post castigates the Weekly for its supposed “angle” and says, “The word is that the Weekly is a pretty sucky place to work.” Harris, who moved here from Boston in the ’90s, also criticizes the paper for hiring “out-of-towners.”)

Portland’s Street Roots director, Israel Bayer, also disagrees with the notion that street newspapers enable people who don’t want “real” jobs. “Poverty is a swinging door,” Bayer says. “What happens to that individual if he stops selling? Does he fall back into poverty? Are there living-wage jobs out there? The reality is that there’s no one out there panhandling or selling a street newspaper that’s living in the bling-bling.”

Perhaps not, but Warren Goulet, who’s been selling Real Change for three months, doesn’t think vendors should be able to squat their locations once they’ve gotten themselves off the streets. “If they make money and can afford housing, let other people have a chance,” he says. “I’d like to get a regular job. I don’t want to do Real Change forever.”

Osuri admits that even she wonders if she should try to transition her best vendors to other types of work. “It’s a big question,” she says. “Honestly, we don’t do anything. We just try to promote Street Sense as a stepping stone, and hopefully these other vendors realize that.”

A few blocks west of McClain, a Real Change vendor named John stands outside a Trader Joe’s with his papers fanned out like a winning rummy hand. John, who asked that his last name not be used, survives on a monthly $339 check from the government, plus whatever he makes through Real Change. He shares a $450-per-month apartment with his brother up the street. “I’m not supposed to be doing this, but this is how I pay my rent,” he says.

John pauses to sell Carrie Nelson a paper. “Yeah, I know not everyone is homeless,” Nelson says. “It doesn’t bother me at all. At least the money is going to a newspaper.”

Trader Joe’s isn’t John’s normal vending location; a video store a few blocks away is. According to Real Change‘s turf system, vendors who sell 300 copies per month at a certain location get dibs on the spot for half the day and can ask other vendors to scram. Those who sell 600 copies each month have dibs for the entire day. Vendors have their 300 Club or 600 Club membership identified on their badges, which also state the location and vending times of their turf.

“The turf system is the soul of Real Change,” says Harris. “It’s what creates the transformation in people’s lives. People see the vendors, get to know them, and it builds continuity in the community. And the turf system drives our circulation.”

But the system, though intended to quash fights among vendors and reward those who have built up their locations, can also lead to quarreling.

“The irony of Real Change is that while it promotes social justice, lack of greed, cooperation, and nonviolence, it doesn’t play out like that on the street,” says Paul, a 300 Club member at Trader Joe’s. “It inadvertently, through its policies, promotes the opposite. Basically, Real Change is taking a group of people with a mental-illness rate of 60 percent and putting them in a very competitive situation that would increase friction even among people who normally get along.”

Paul, who also asked that his last name not be used, points to the deal that Real Change gives its best vendors: The top three sellers each month can buy their papers for 30 cents instead of the regular 35 cents. “How different is that from giving tax breaks to the rich?” wonders Paul.

“The opportunity is there for everybody,” insists Jim O’Donnell, a 600 Club member and the February vendor of the month. “Seattle’s a major city in the country. You can always have more vendors.”

“I’ve seen vendor conflict within and without the turf system,” Harris says, “and there’s a lot less with the turf system.”

Paul sleeps under the stars in Ravenna Park, but until recently was living with O’Donnell. He says he felt guilty selling Real Change, knowing his buyers assumed he was homeless. “I’m out there now, though, and I feel considerably less guilty,” he says.

But Paul says he still wrestles with his conscience when someone pays him more than a dollar for a paper. “There’s a panhandling aspect to this,” he says. “I’m not asking for $10 for a paper. I’m asking for $1. It’s panhandling-lite.”

McClain cops to having no problem with taking more than the suggested donation. “I don’t care why you give me $5,” he says. “I don’t care if you give me $500. I’ll take every free penny you give me. My first paper today, I sold for $20. You can bet if she came back for some change, she wasn’t getting it, no sir. It’s mine.”

According to Real Change‘s 2007 strategic plan, the company aims to: “Begin [the] process of positioning Real Change within the human services community as a low threshold employment opportunity that offers access to next-step employment.” Harris says he hopes to develop closer relationships with job training and placement agencies. “Selling Real Change isn’t a retirement strategy,” he says. “It’s not a substitute for job security or benefits.”

But Harris stresses that any transition of Real Change vendors to other jobs would be purely voluntary. “Ed McClain is successful,” says Harris. “He enjoys what he does, finds meaning in his work; he’s not making a lot of money, but it’s enough for him. If Ed wanted to move on, I’d be the first person to help with that. But if Ed is happy selling Real Change, I’m not going to pull the rug out from under him with the idea that we know what success looks like for him better than he does.”

When Michael Garcia, 46, got out of prison a couple of years ago, his record, which included a felony for selling heroin, prevented him from securing either a job or an apartment lease, and one of the few ways to legitimately make money was selling Real Change. Garcia, who lived in a shelter for six months, now stays with his girlfriend on Lower Queen Anne and says he’s up front about his housing situation with his customers at a downtown Starbucks. Selling Real Change, he says, is a job like any other, and it wouldn’t be fair to put an expiration date on vendors.

“It’s not like the Seattle Weekly would tell one of its reporters to leave because he’s too good,” says Garcia. “People will move on when they’re ready to move on.”