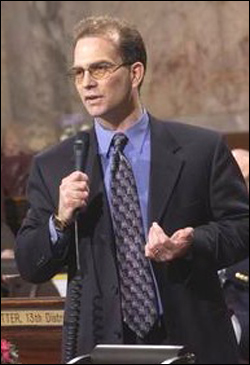

WHEN IT COMES to health insurance for mental health in Washington, there’s only one name you need to know: Joe Zarelli. He doesn’t head an insurance company. He’s a security consultant and Republican state senator from Ridgefield, in Clark County near Vancouver, and he’s chair of the powerful Ways and Means Committee. On Monday, Zarelli killed a well-supported bill requiring that insurance coverage for mental-health treatment be at parity with medical services. Over the past decade, 38 states—including progressive leading lights like Arkansas and Alabama—have enacted similar insurance parity laws.

HB 1828 passed the Democrat-controlled state House on Feb. 13 by a 64-33 vote, with 13 Republicans in support, but it never got a hearing in the Republican-controlled Senate. Monday, March 1, was the final day that bills could be reported out of legislative committees. Zarelli, the first-session Ways and Means chair, told Seattle Weekly that he didn’t find the matter a pressing responsibility, conceding, however, that he had not examined it. By not ordering a hearing for HB 1828 in his committee, Zarelli prevented the bill from reaching the Senate floor, where it would have passed, according to members of both the Republican and Democratic Senate caucuses. Gov. Gary Locke has quietly advocated for the bill and would have signed it, his office said.

How could one man quash a bill that would have helped tens of thousands of Washingtonians, including, perhaps, members of the state Senate, and maybe saved a few lives as well? “I don’t know the issue,” Zarelli said Monday. “It’s a hot potato in a lot of people’s minds.”

Strangely, the Washington Coalition for Insurance Parity isn’t particularly upset. “The farther you get, the better you are,” says Randy Revelle of the coalition, noting that an earlier version of the parity bill had never cleared even the House. Revelle is a former Seattle City Council member and former King County executive. “As long as you make that progress, you are in great shape.”

UNDER WASHINGTON law, it is legal for insurers to provide two-tiered coverage—one for treatment of the body, another for mental health. Under this system, visits to a doctor or therapist can be limited to as few as six per year. With conventional wisdom being that regular meetings with a therapist are crucial to any mental-health treatment, such a limitation doesn’t make sense. Moreover, it’s not uncommon for co-payments of upward of $50 per office visit for mental-health care, compared with $10 for standard medical treatment. Mental-health consumers also face lesser insurance benefits for prescription coverage and no protection against catastrophic expenses—the so-called stop-loss provisions enjoyed by other patients. The current law is devastating for those who can’t afford treatment and for those who are acutely ill, but it also greatly affects people who are not as impaired—who are fully functional but do best with regular doctor or therapist visits and ongoing use of medication.

The consensus of scientific opinion in the U.S. is that mental illnesses are, in fact, physical ones. In 2002, a federal court judge in Washington, D.C., ruled that bipolar disorder—the second most common mental illness behind depression—meets the legal definition of a physical illness. Besides being unfair and illogical, unequal coverage creates disincentives for the mentally ill to get treatment, and when the mentally ill go untreated, society as a whole suffers, or pays, in one way or another. HB 1828 states “that the costs of leaving mental disorders untreated or under-treated are significant, and often include: decreased job productivity, loss of employment, increased disability costs, deteriorating school performance, increased use of other health services, treatment delays leading to more costly treatments, suicide, family breakdown and impoverishment, and institutionalization, whether in hospitals, juvenile detention, jails, or prisons.”

BEGINNING IN THE early 1990s, parity bills were first introduced around the country. They faced intense opposition from insurance companies and business associations, who argued that expanded coverage for the mentally ill would raise health insurance costs and force businesses to offer their employees no health insurance whatsoever. As it turns out, they were wrong on both counts.

The experience of states with parity laws and of the federal government, which has insurance parity for federal employees, is that costs barely increase and that employers don’t yank insurance plans, according to the American Psychological Association. A study of the parity system in Vermont by an insurance actuary shows that premium costs went down, despite the fact that the mental-health system was being used by more people. In testimony before the Colorado Legislature, an official with PacifiCare, a large insurer in Washington, stated that parity in that state increased costs by $1 to $4 per person per month.

Zarelli didn’t know any of this. In an interview, he admitted that he had no idea how many suicides—the most extreme measure of mental-health care needs—there were in his district, which covers portions of Clark and Cowlitz counties. In 2002, there were 66, a 38 percent increase over 2001. Nor did Zarelli know that nationally there has been a more than 30 percent decrease in the teen suicide rate since the mid-1990s, largely a result of teens’ willingness to own up to—and get treatment for—problems that adults often refuse to grapple with, or can’t afford to. Even former U.S. House Speaker Newt Gingrich, a pre-eminent conservative, supports mental-health insurance parity.

ZARELLI HAS BEEN a state senator since 1995. The parity bill has been introduced in the Washington Legislature each year since 1997. His claim not to know the issue is particularly odd in light of the fact that he voted on a previous parity bill, on the Senate floor in 2001. He voted “no.” If Zarelli didn’t make an informed decision now, presumably he cast an informed vote then.

In 2001, there was organized opposition to the bill from insurance companies and business groups. Their principal gripes were feared costs and the idea that the new coverage would be “mandated”—something insurers and business groups can’t stand.

This year, however, there was no organized opposition to HB 1828. Even large insurers like Group Health Cooperative and Premera Blue Cross were silent, according to spokespeople for the two companies. Mysteriously, though, there was silent opposition in the Senate. Take Sen. Linda Evans Parlette, R-Wenatchee, who is vice chair of the Ways and Means Committee. She also sits on the Senate’s Health and Long-Term Care Committee, which last week forwarded the parity bill to Zarelli’s committee. In 2003, she raised $15,000 in campaign contributions, $10,875 of that coming from the health care industry. Asked her thoughts on the bill, Parlette said, “I want to know whether insurance carriers were involved when the bill was drafted.” She added that she was very nervous at the prospect of the parity bill being heard before Ways and Means without insurance industry representatives present.

In that kind of environment, it was easy for Zarelli to spike the bill, even though Parlette and state Sen. Lisa Brown, D-Spokane, both said that there were enough votes in the Senate to pass the measure.

IN OTHER WORDS, this bill should have passed. The coalition backing mental-health insurance parity can afford to be sanguine—they’ve made huge progress, after all, and expect to get the bill through both houses next year. But each year, about 800 people kill themselves in Washington. The state’s suicide rate was 26 percent above the national average in 2002. There are people who simply do not have another year to wait.

“It’s really disappointing to me that it was held up by political machinations than by any genuine policy reason,” says Brown, who promises to reintroduce the bill next year. “I don’t believe that mental health should be seen as a mandate. It’s more an issue of continuing to discriminate against people.” Says Revelle: “It’s the right thing to do—no one argues against that. No one who opposes it has produced one document or study that disagrees with what we say.”

Yet, like others in the coalition, Revelle won’t criticize the lack of movement in the Senate this year. They don’t want to poison the bill next year—particularly if Zarelli still chairs Ways and Means.