Matthew Sparke sits at the head of a table in a first-floor classroom in the University of Washington’s Smith Hall on a May afternoon and asks the 15 students before him to contemplate a thought-provoking question: Why would an antipoverty project in Africa feel the need to trademark its work?

“Are you afraid someone might steal it?” the red-haired, British-born professor asks with a wry chuckle. Sparke, the winner of a 2007 distinguished teaching award from the University of Washington, displays humor and a boyish sincerity when engaging with his students. Like many professors, he uses academic jargon like “meta-discourse” and “spatial selectivity,” but he’s otherwise lacking in airs. It’s perhaps one lasting effect of being told at age 11, after failing a critical test then given in Britain, that he had no academic future. He went on to Oxford University anyway.

There’s a pause while the bright-eyed, 20-something seniors, who signed up for this “global health and philanthrocapitalism” class as part of their studies in the prestigious Jackson School of International Studies, consider the question, which is directed at an enterprise called the Millenium Villages Project. “You don’t want somebody to use the name and then mess it up,” ventures a young man.

“Ah-ha,” Sparke says. “So what does that tell you about his vision?” he asks, referring to Millenium Villages’ founder Jeffrey Sachs. The geography professor goes on to mention that Sachs seems to have an ego, and prompts the class to mull over whether today’s philanthropists are like the “charismatic leaders” of old, deriving their power from an image of godlike “beneficence.”

Further contemplation of Sachs leads a student to question his seeming obsession with “data,” which leads to a discussion of a similar obsession on the part of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which meanders back to the proprietary attitude of philanthropists.

In Africa, says a young woman who has traveled there, “every village has a sign that says what NGO worked there—like [the villages] were owned by the NGOs.” It’s a keen observation that gets at the heart of a point Sparke is trying to make. “There is this weird way in which Africa becomes a tableau for all these foreign flags,” he elaborates. It’s a “turf war,” he continues, albeit one that has to do with “saving lives.”

This class embodies a lot of what is good about the university experience, with its opportunities for give and take between curious students and knowledgeable scholars. When it ends, however, Sparke rushes out and heads across the quad to Savery Hall, where he makes a presentation before the Faculty Senate about a major new university initiative that is, in a way, antithetical to that experience.

Sparke has just been named the head of a program that will offer a full complement of social-sciences classes online. The so-called Integrated Social Sciences Program—which, if all goes as planned, will launch in the fall of 2014—is fueled by a frenzy for online teaching that has hit higher education, in the words of Stanford University President John Hennessy, like a “tsunami.” Much of that energy is sparked by what has become known as MOOCs, or Massive Open Online Courses. They are wildly popular, and there’s a key reason why: These university classes, offered over the Internet and consisting largely of video lectures broken into short chunks suited for the attention span of the wired age, are open to all comers, whether in Seattle or Shanghai. And they are free. One 2011 Stanford class in computer sciences famously drew 160,000 students.

But MOOCs are also wildly controversial. In early May, members of the philosophy department of San Jose State University wrote an open letter to a Harvard teacher offering a MOOC course on social justice. SJSU had signed a contract with edX, a nonprofit partnership between Harvard and MIT that produces MOOCs, and the California school’s president wanted to test the online Harvard material as part of the regular philosophy curricula. “Let’s not kid ourselves,” the philosophy professors wrote, explaining why they were refusing to follow their president’s wishes. “Administrators at the CSU [California State University] are beginning a process of replacing faculty with cheap online education.”

Financial Times columnist Christopher Caldwell believes their fears are warranted. “The Internet is about to bring to university professors what it has brought to secretaries, journalists, and music executives: unemployment,” he wrote in a piece last year.

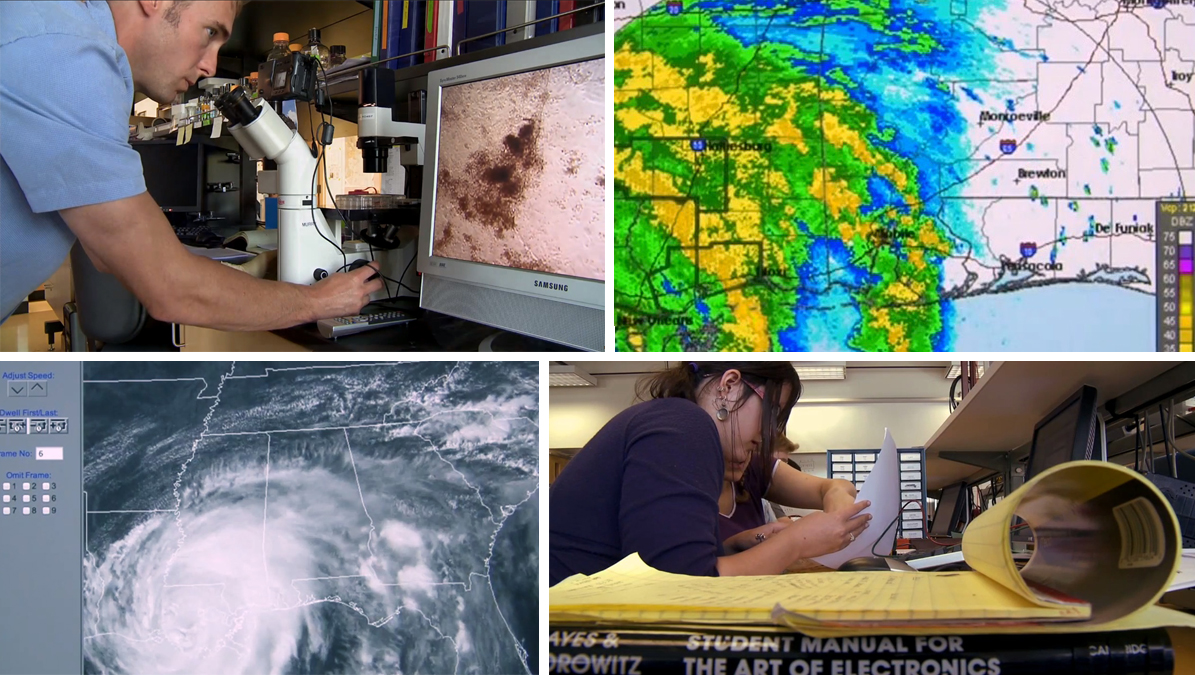

There are also concerns that the online craze will narrow the range of intellectual thought, as universities around the country rely on digital classes taught by professors at just a few prestigious schools. Plus there is the question of the classroom experience, which can perhaps be approximated (through, for instance, discussion boards), but not quite replicated, online. In a brick-and-mortar class, says Cliff Mass, UW’s renowned professor of atmospheric sciences, “there’s something important and magical that occurs.”

Yet the traditional university, with its spiraling costs, is facing scrutiny as never before. Josh Jarrett, deputy director for post-secondary success at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, is one of a growing number of people skeptical about how well the magic is working. He says only about one-third of low-income students who start college make it to graduation. What’s more, he says, “we’ve known for 30 years” that there are better ways to learn than the classroom experience—namely one-on-one tutoring, shown in decades-old research to be more effective. “We can’t get everyone a tutor, but we can blend the best of what faculty can do with what technology can do,” he says.

Facing such sentiments, the prospect of being left behind in the online craze, and the allure of technological innovation, UW has jumped into this new world. Last summer, it started offering MOOCs through Coursera, a for-profit company started by Stanford professors. And in May, the university announced that it would also work with edX.

David Szatmary, UW’s vice provost for educational outreach, which handles online initiatives, calls the university’s MOOC offerings “an experiment.” And it comes with some risk. While MOOCs are free to students, they are costly to produce. Karen Dowdall-Sandford, head of online programs in Szatmary’s department, says she budgets as much as $29,000 for video production, “instructional designers” who help professors plan their online content, and project managers. That doesn’t include the extra month’s salary the university pays professors to create a MOOC. The university, which does not use taxpayer money for MOOCs, got a $50,000 grant to develop one on public speaking that ran over the summer.

Nathan Kutz, a professor of applied mathematics who has offered some of the UW’s first MOOCs, observes that universities “are looking like they might lose their shirts unless they can find a way to monetize.”

In this respect, the program headed by Sparke offers another way forward. Its online classes will not be MOOCs. The program is, in fact, a degree completion program, targeted at the millions of students not just in this state but around the country who have taken some college courses but dropped out. Students will pay tuition, albeit much less than what their on-campus counterparts pay.

It is an experiment—one that generates mixed feelings on campus. “The Faculty Senate has been concerned that we don’t rush foolishly into untested waters,” says Jim Gregory, the senate president. At the same time, UW economics professor Dan Jacoby observes of online teaching: “Everywhere you look across the country, there’s a sense that it’s coming.”

“I don’t have strawberry jam in my teeth, do I?” Sparke half-jokes.

“No, you’re good,” says Ryan Adams, who with cameraman Lars Myren is filming Sparke in front of Smith Hall on a beautiful June day. “Let’s roll.”

Sparke hesitates. “How does ‘Greetings’ sound?” he asks. “Do you think it sounds weirdly English?”

“Yeah, but it’s great,” Adams says. “Whatever you’re comfortable with.”

Sparke begins a take, looking at the cameraman. “So greetings! In this introductory video, I want to give you a sense of where I’m coming from, both physically and intellectually. Come with me, up to my office.” Sparke walks up the stairs into the building and makes his way to his third-floor office. Trailing him with a hand-held camera are Adams and Myren.

“What we’re doing today is like a short film,” Adams explains during a break between takes. Before being hired by UW a little over a month ago as a full-time video producer, he worked in TV and movies. He served as director of photography on The Oregonian, an independent horror flick that went to the Sundance Film Festival in 2011, and last year he shot a Mike Birbiglia Comedy Central special.

He says he took this job in part to have a steady income. But he waxes enthusiastic about the opportunity to tell what he calls “educational stories” in a more polished way than has often been the case. When you look at MOOCs, he says, “a lot of them are webcams in people’s offices. They’re dreadful.”

He says he’s also excited about helping UW professors reach a wider audience. As of yesterday, he notes, the public-speaking MOOC had 80,000 people enrolled. “Those are like successful indie-feature numbers!”

The footage he’s filming today is intended for both a MOOC—to be offered on Coursera in the fall—and for a meatier class that could become part of the new online social-sciences program. The topic is globalization. But Sparke doesn’t want to dive right in. He wants this introduction to give students in far-flung places a more personal connection to him and the university environment. In a way, he sees these online courses as breaching the “town/gown divide,” exposing academics to people who might not otherwise set foot on a university campus.

In his office, shades drawn, an imposing piece of lighting equipment called a chimera set up in a corner, Sparke again turns to the camera. He calls attention to a picture sitting on the bookshelf that lines one wall. It’s of his own class of freshmen, or “freshers” as they were called, at Oxford, he explains. “There I had my first important intellectual experience,” he goes on, referring to a geography professor he had named David Harvey. “You can see books on the shelves by him.” Sparke waves an arm to point them out. As he does so, he knocks over the Oxford class picture.

“Ah, shit,” he exclaims. By this time, he’s already done quite a few takes—walking upstairs to his office and then back down, saying less or more, “landing” in the spot indicated by Adams, correcting slips of the tongue—and he’s getting flustered. “I’m not sure I’m cut out for this,” he confides at one point, a couple hours into shooting. A few takes later, he asks for a break: “Can we get a coffee? I’m exhausted.”

Taking a seat, his gaze falls on a picture of the scenic Lake District in England, where he spent holidays as a child. He used to hike, but not with his dad. Having suffered brain damage at birth, the elder Sparke was disabled. Sparke says his dad managed to get a job as a clerk at an insurance company, but stagnated in that lower-level position.

In an earlier conversation, Sparke noted that he loved America’s willingness to give people second chances in life. Indeed, he said, that ethos was part of what drove him to get involved with online education, which he believes opens new “learning opportunities.” Now, alluding to his father, Sparke reflects, “That’s also why I believe in second chances—because he never got one.”

His break over, Sparke continues filming. He will spend the rest of the day behind the camera, taking his crew downtown to film the setting of the 1999 World Trade Organization protests. Unfortunately, it will prove too noisy a spot, and Sparke fears the footage may need to be scrapped.

Egalitarianism runs through the online-education movement, which is older than many people realize. As far back as the 1990s, the UW began to offer online courses, says Szatmary, the head of educational outreach. The digital offerings, most of them part of graduate degree or certificate programs, generally cost money. But since 2001, about a dozen online classes have been free.

Szatmary says that the university considers the free offerings a public service, in keeping with a mission to provide broad access to residents across the state. And in fact, that tradition goes back way before the digital age—to 1912, when UW launched correspondence courses, with textbooks and assignments traveling back and forth by mail.

Yet it was not until the nation’s most prestigious universities began to offer free online courses a couple of years ago that the phenomenon captured worldwide attention. What was in the offing was nothing less than an “Ivy League for the masses,” proclaimed Time.

The appeal of MOOCs has been potent. The skyrocketing cost of higher education is causing national panic. In the ’80s, UW’s tuition amounted to less than $1,000 a year. It now tops $12,000. Add room and board and you double that. At Ivy League schools, the total bill runs close to $50,000 a year. “We’re facing a crisis in this country,” says Larry Seaquist, chair of the state House Higher Education Committee. It was a point much discussed in the last legislative session, which ended, for the first time in decades with no tuition increase.

The cost is increasingly prompting people to ask a heretical question: Is a college education worth it?

Peter Thiel, a libertarian education reformer and venture capitalist, likes to talk about what he calls an “education bubble,” which overvalues the college experience just as the real-estate bubble once overvalued houses. A foundation he started in San Francisco finances a select group of college students to drop out and pursue other work, in the tradition of such notables as Bill Gates.

“Maybe there are more effective ways of learning than spending four, five, six years in college and racking up hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt,” says Thiel Foundation president Jonathan Cain. Those ways, he says, could be “new online models.” If they don’t offer credit, so what? Cain calls a B.A. “meaningless.” What’s important, in his view, is whether young people get the “knowledge and skills they need.”

For many people, of course, college is about more than knowledge and skills. Consider, for example, Fiona Stefanik, a 20-year-old UW senior sitting one sunny day last spring on the sprawling lawn outside Smith Hall. All around her are students doing the same, or reading or talking with friends. It’s the kind of idyllic scene that goes into college brochures.

Stefanik says she thinks of college as an “experience.” She adds, “It’s about figuring out who I am.” She relates that she started UW as a “die-hard” pre-med student, but found herself stressed out and miserable by sophomore year. Then she took an anthropology class.

“I just fell in love,” she says. She explains that anthropology, which she’s now majoring in, gave her a way of understanding the world. And she really connected with the class’s high-spirited professor, who started every class by leading a group dance session. She believes that none of that would have happened had her education been online.

That’s undoubtedly the case. But other students are willing to dispense with the experiences of campus life. And in Cain’s subversive vision, the online students of the future won’t necessarily need to make such stark trade-offs. He contends that new online entities will spring up to serve some of college’s auxillary functions.

It’s a model certain to produce shudders from university figures. They already see private schools, like the University of Phoenix, as bugaboos, making a profit while they siphon resources from the publics and nonprofits. And many academics find it alarming that venture capitalists are moving into online learning. Most notable, Coursera has raised $65 million in private funding as of July. What do investors see in a company offering free classes? In a widely circulated open letter to Coursera co-founder Daphne Koller, University of California professor Bob Meister speculates that the classes won’t be free for long. Coursera, he suggests, has a hidden profit-making agenda.

Sparke says he has “critical concerns” about this possibility. Yet despite those, and despite the subversive notions of people like Cain, Sparke and other academics see an upside to MOOCs. Given that he’s teaching about globalization, Sparke likes the idea of students from all over the world contributing to online class discussions.

Kutz, chair of the applied-mathematics department, articulates another reason that university administrations might find MOOCs appealing. “It’s a great marketing tool to highlight what we do.” The two he taught last year, in scientific computing and data analysis, each drew around 14,000 enrollees, many of them in India, Africa, and South America, all of them now exposed to the UW and its expertise in applied math.

Kutz’s personal exposure has also grown—he’s become a MOOC mini-celebrity. Walking around Boston this past year while on sabbatical, he’s had students from his online courses stop him excitedly. His celebrity is apparently not unique. The Chronicle of Higher Education recently reported that some MOOC professors gain such a following that students have entertained the idea of printing T-shirts adorned with their faces.

Kutz notes that digital lectures have some distinct advantages for students, something he says he learned teaching in an online master’s-degree program offered by his department. To his surprise, he found that the videos he made for the online program were popular even with on-campus students. He realized that in a traditional lecture, a student’s attention can drift. He can see it in their faces, and he’ll try to bring them back with a joke. Yet online, he says, students who miss a moment can simply rewind. Those who get bored by a lecture’s slow pace can, alternatively, speed up the playback.

Still, he’s concerned about the financial aspect of MOOCs: “It’s one thing to challenge $50,000 tuition, but zero dollars—that doesn’t make sense.” Given the financial drain, UW negotiated a special deal with Coursera, Kutz says. As Coursera offered the UW’s MOOCs, it would give students an opportunity to switch into upgraded courses with the same rigorous assignments and evaluations given on-campus students. Those who switched would also pay roughly as much as if they were in the actual classroom, and in return receive academic credit or a certificate. Through those fees, the university figured, it might be able to recoup its expenses on the MOOCs.

Bellevue’s Karen Boher took the bait. The 57-year-old software developer and business-management consultant had just finished getting a UW master’s in business administration the old-fashioned, on-campus way. Wanting to launch a start-up, she recalls, “I still felt like a few pieces of the puzzle were missing.”

Previously she had discovered iTunes U—a service of the iTunes store that, much like Coursera, offers free university lectures—and became enraptured with the ability to learn from professors at places like the London School of Economics. She sampled courses as if they were ice-cream flavors, trying a little bit of this, a little bit of that. “They’re free, so if you get too busy, you can drop out,” she says. That’s typical. Szatmary says the latest figures he’s gotten from Coursera reveal that only 3 to 5 percent of people who enroll in a course finish it.

Boher turned to Coursera to find her missing pieces, and saw a UW MOOC on information security that interested her. She enrolled. And she loved it. But she also knew that an on-campus class was going on at the same time, one that promised more extensive readings, up-to-the-minute lectures, guest speakers, and interaction with the professor. “I couldn’t stand what I was missing,” Boher says. So she upgraded on Coursera, which allowed her to virtually attend the on-campus course. She ended up taking two additional courses that way and received a certificate in information security and risk management.

At a south Seattle Starbucks, Boher fires up her laptop and clicks on a link to bring up a class from the spring. In a little box on the left side of the screen, we see the professor, Mike Simon, standing in front of a white board. He tells the students in the classroom—whom we can hear but not see—that he’ll wait a few more minutes for others to trickle in. In the middle of the screen is a big space for PowerPoint presentations. In a column on the right side of the screen, texts from online students are appearing.

“It’s been a very busy week,” texts an online student, revealing that his workplace has experienced a security breach. “All applicants and employees potentially had exposed SSN, birth date, maiden names, etc.”

Those in the classroom can see the texts, which are projected onto a screen. Boher notes, though, that in the first class she took, the professor was sometimes slow to look at the screen and respond.

Technical glitches also emerged. In the class we’re looking at, another online student attempts to give a presentation using his computer mike, but his voice keeps fading out. All of a sudden he appears onscreen, a young man wearing a red beard, a baseball cap, and a look of utter frustration. He still can’t be heard. The professor moves on to another student.

These problems didn’t bother Boher much. Being local, she was able to drop into the classroom occasionally. And because of the online dimension, she enthuses, “we had people from all over the world in class.” Via Skype, she worked on projects with students from India, Italy, and Canada. “It was a little hard because we had three different time zones,” she says. They worked it out.

The biggest problem of these upgraded Coursera classes affected not students but administrators: There simply weren’t enough takers. Boher was one of only nine last year who took the leap into paying for courses.

“It was at best a mixed experiment,” Szatmary concludes. The university recouped about $36,000, but spent more than $100,000 developing the MOOCs that could be upgraded, according to Szatmary. Even so, he says the university will continue to develop free classes—but in limited quantities. “We’re not poised to offer dozens of courses,” he says.

UW President Michael Young acknowledges the question facing many schools that have leapt into offering MOOCs: “How do we monetize?”

Speaking by phone one day this summer, Young expresses an interest in online delivery. In addition to providing increased access, he says, he sees it as a potential way to create “efficiencies” and make education more affordable. Yet, in contrast to education radicals like Thiel and Cain, he’s quick to opine that MOOCs don’t add up to a genuine college education, which he holds is not only about “content” but “transforming young minds.” That’s why he says he’s adamantly opposed to offering credit for MOOCs—a line in the sand that also looks out for the university’s bottom line.

Young is betting, however, that the university can transform young minds through a more systematic online education. He’s the one who came up with the idea of a degree-completion program for college dropouts. Aware that this demographic is considerable, he says he asked his staff soon after arriving in Seattle from the University of Utah, where he was previously president, to explore the idea. “I don’t want a UW Light,” he says he told his staff. “I don’t want [online] classes to be bigger than 35 or 40 students . . . And could we do it for half the price?”

That’s cheap, but a lot more than nothing; the tuition currently under discussion is roughly $7,000 a year. The goal is to break even. By doing so, Sparke points out, the university will potentially get something it has been seeking for a long time: the ability to hire new staff. That hasn’t been possible for years, given slashed funding by the legislature. Sparke refers to the faculty as a “graying population,” causing low morale in departments hungry for fresh talent. The proposed social-sciences program won’t generate a ton of new hires, Sparke cautions—maybe only four or five a year. But in a small way, he says, it “will allow us to basically expand the university.”

Last fall, Szatmary came to a Faculty Senate meeting to outline the idea. Faculty members peppered him with critical questions. Many felt it was a vague, top-down notion that had more to do with “a desperate need to get online” than with a concrete educational mission, says Robert Wood, head of the UW chapter of the American Association of University Professors. He also recalls that Szatmary’s presentation, complete with market-research figures, sounded off-puttingly like a “business plan.”

And while UW had a long history with online programs, this one proposed “to cross a different threshold,” explains senate president Gregory. He points out that existing degree programs offer specific skills to graduate students. This new program, however, would be for undergrads seeking a more general, broader education. The students would be younger. Could their needs really be met online?

Jacoby, the economics professor, says his worst fear is that programs like this will create “more of a class-based system,” with those who can afford it getting the full on-campus experience and those who can’t relegated to the online world. What makes this particularly alarming, in Jacoby’s view, is that those who can’t afford it are precisely the people who most need the support of an on-campus education—faculty engagement, peer-group morale-raising and reinforcement of study habits. It’s a view that counters the sunny egalitarianism that others see in online education.

The administration wasn’t proposing to start small with this new venture, moreover. It indicated that its goal for the social-sciences program was to enroll 5,000 students within five years—almost the size of last year’s freshman class.

To move ahead with such a program, the administration needs the approval of two Faculty Senate committees. While debate simmered over the social-sciences proposal, the administration came forward with another proposal for a much smaller bachelor’s program, one narrower in scope—offering a degree in early-childhood and family studies that would enroll maybe a couple hundred students. The proposal responded to a new federal requirement that half of Head Start teachers have a college degree.

Faculty felt it was “a good way for UW to test the waters,” Gregory says. The requisite Senate committees gave it the go-ahead in the spring, and the program will begin this month.

Meanwhile, the administration continued to work on the social-sciences idea. In the spring, it named Sparke to head the program.

In a big lecture hall filled with 100 or so faculty members, Sparke takes the podium with characteristic cheerfulness. It’s his May presentation before the Senate, the first time he’s appeared in his new role.

He declares himself excited about “using online education to expand the University of Washington’s teaching vision.” But he acknowledges ongoing debates over online teaching. He references San Jose State. There, he says, professors face the prospect of “being reduced to the level of a TA [teaching assistant].” The UW program, Sparke stresses, is “an insourcing model rather than an outsourcing model.” Sparke also notes that the program will offer “mentoring and coaching”—a point reiterated by Judy Howard, dean of social sciences, who takes the podium next. She talks about “e-nags” who will check up on students.

Exuding competence and self-assurance, Howard briskly covers other aspects of the program: the intended outreach to marginalized populations, the possible online seminars that will create a “community of learning,” and the desire to avoid a “bifurcated” staff by encouraging all faculty members to teach online classes. “It’s really critical that departments as a whole embrace the program,” Howard says, indicating that as yet this has not happened. “The hardest part” of pulling off the program will be “resources,” she notes, elaborating that it will require more instructors than have currently signed up.

That’s not surprising. On top of all the concerns faculty initially expressed, there is the time commitment involved. Matt McGarrity, the lecturer teaching the public-speaking MOOC, says its development has been “just a massive amount of work,” including preparation, filming, and post-production editing. And while he expresses excitement at reaching a global audience, he also notes that his “obligations are first and foremost to the people who paid to be in the seats here.”

When Howard opens the floor to questions, it’s clear that this faculty reception is far more positive than the one that greeted Szatmary in the fall. A woman in back raises her hand. “The academic substance of this is just wonderful to behold,” she gushes. “This has the potential of creating something that could be a model for the rest of the country, if not the world.”

“This sounds pretty impressive,” Gregory chimes in.

Talking with Seattle Weekly later, the Senate president explains that the idea seems more carefully fleshed out than when it was first proposed. Of Sparke and Howard, he says “They are thinking deeply about what can be done in online courses.” Both have earned much respect from faculty, and have lent the program credibility. Consequently, by mid-August, upward of 30 instructors had signed on, as many as needed to launch the program next fall.

Sparke is open about his deliberations. He concedes that one big challenge will be to make good on the program’s “degree-completion” billing, with reference to students who have already dropped out once. He hopes to keep students engaged through the e-nags (or e-advisors, as he prefers to call them), webinar office hours, and “interactive spaces.”

Also prompting much discussion in recent months, Sparke says, is “risk management.” As with MOOCs, UW is not tapping into taxpayer funds for the new program, which is meant to be self-sustaining. So the university needs to be careful about how much it spends and realistic about the program’s possible enrollment.

Just in the past six months, “things have changed a lot,” Szatmary explained by phone a few weeks ago. Such is the rush by universities to get into online teaching that UW faces ever more competition. The University of Florida, the University of Wisconsin, and Colorado State University have all launched online programs. Their enrollment results have been mixed, according to Szatmary. UW administration has consequently downsized its ambitions, now saying it wants to enroll 1,250 students in three years rather than 5,000 in five.

“We’re going slower than some would like,” Sparke allows. Yet, he says, even the scaled-back program is “quite a big beginning.” A couple of weeks ago, having just finished the proposal that will go before a Faculty Senate committee on academic standards, he was mulling over where to find office space for the three new advisors who will be hired. Also, he’s scouting locations in his mind for the 10 remaining days of filming he has yet to do. He’s thinking about the Port of Seattle and Boeing Field to illustrate points he wants to make about globalization. But he knows enough now to make sure that the background noise won’t interfere with how he comes across on the little screen.