Will this be the year local voters finally get “tax fatigue”?

As we’ve previously reported, state restrictions on local self-taxation force Seattle and King County leaders to place levy after levy and tax after tax on the ballot for voter approval, year after year. And year after year, voters have said yes. Last year they approved a 25-year, $54 billion plan to expand light rail and other regional transit, as well as a seven year, $290 million city levy to fund affordable housing. The year before, Seattle voters approved a 9-year, $930 million city transportation plan to replace the expiring one. The list goes one, but you get the point: there is a long string of instances of voters approving big self-taxation plans.

And there are more coming down the pike. During his annual State of the City address last month, Seattle Mayor Ed Murray announced plans to ask voters this fall to double Seattle’s homeless funding, with a five-year, $275 million property tax. (The Seattle Times’ Dan Beekman has more details here.) Last week, King County Executive Dow Constantine announced that voters will also consider a seven-year, $469 million measure to fund arts, science and “heritage” programs for students and low-income residents.

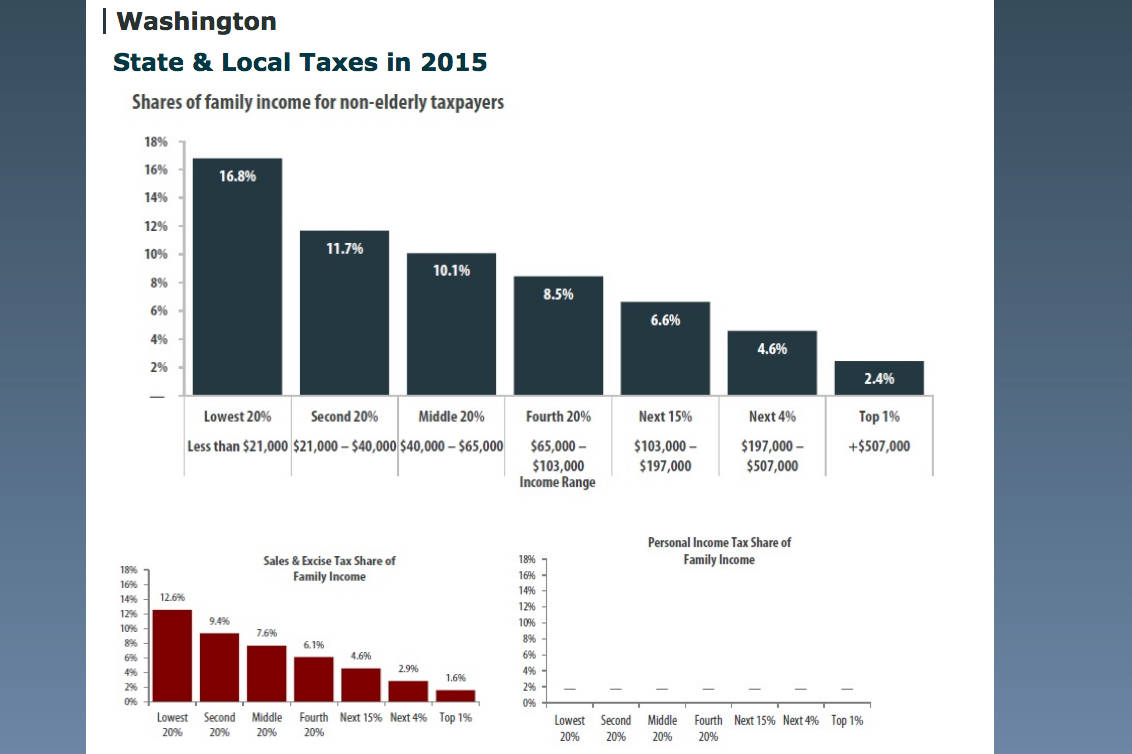

County Councilmember Dave Upthegrove responded skeptically to the latter proposal. In a press release, he reiterated the oft-made point that that sales taxes are regressive (because poor people spend a greater share of their income on consumption than rich people, who invest). “This proposed sales tax increase would hit low income folks the hardest,” he said. “Our state already has the most regressive tax system in the country, and this would make it even worse in King County.” Upthegrove said he’ll take “an honest and hard look” at the proposal.

Upthegrove’s reaction to Constantine’s proposal shows two progressive values in conflict: opposition to regressive taxation versus support for social programs. The fact that state Republicans have been able to turn tax-and-spend into a divisive issue for local Democratic officials is stroke of evil genius. “Do you want to tax the poor, or do you want to cut social programs?” is not a question anyone in the city or county wants to have to answer.

The answer progressives would love to give is, “I want to tax the rich.” But the most straightforward way to do so—a graduated income tax, wherein higher earners pay higher rates—is illegal in Washington…unless it’s not. It’s complicated.

Several times during the Great Depression, Washington’s voters and legislature approved graduated taxes on personal or corporate net income. In the 1933 case Culliton v. Chase, the state Supreme Court ruled that graduated income taxes violate the state constitution’s requirement that all taxes on the same class of property be uniform because, supposedly, money is a class of property. Actually, that’s not quite right: that ruling by a lower court was appealed to the state Supreme Court, one of the justices was out sick, and the other eight were evenly split for and against that lower court’s ruling. In the case of such a deadlock, the lower court’s ruling wins by default.

It’s not clear that the current state Supreme Court would stick that 1933 precedent, though, if another graduated income tax were challenged before them. Writing in the University of Puget Sound Law Review in 1992, Hugh Spitzer argued that the shaky reasoning combined with other new developments in legal precedents would likely (or at least should) lead today’s state Supreme Court to rule differently. Spitzer argues that money is property, an object that belongs to an owner; income is a flow of money, an event that happens once and then is finished. Referring to a Georgia court’s reasoning, Spitzer wrote, “Property is the tree and income is the fruit that can be taxed once and only once: when it is picked.”

With cuts to federal funding looming under the Trump administration, local and state taxation are about to become more essential than ever. So—since we’re going to have to tinker under the hood of our tax code anyway—it’s an opportune time for economic progressives to try and bring back graduated income taxation.

That’s precisely what the Trump Proof Seattle campaign is doing. A coalition of 36 different groups led by the Economic Opportunity Institute and the Seattle Transit Riders Union are proposing “a local tax on unearned income for households with total income over $250,000/year,” according to their website, thus raising $100 million per year in city tax revenue.

Along with raising new government funds, Trump Proof Seattle hopes its measure could clarify that an income tax is legal in Washington. If Seattle sticks to its pro-tax ways and approves the income tax proposal, the plan would inevitably face court challenge and appeals. Voila: the state Supreme Court gets its chance to weigh in on the precedent established in Culliton v Chase, progressives get their chance to pitch for a graduated income tax, and everyone gets closure one way or the other on this still-opaque legal question.

A similar measure made it onto the Olympia city ballot last year, but was rejected by voters.

State Republicans in Olympia are sufficiently concerned about the possibility of an income tax (or, perhaps, excited by the possibility of using the subject as a rhetorical brush with which to paint Democrats outside of King County) that 42 of them are sponsoring a House bill that would send to voters a constitutional amendment explicitly outlawing individual income taxes. “We have the opportunity to pass this constitutional amendment and support what the voters of Washington state have told us multiple times — no state income tax,” lead sponsor Rep. Matt Manweller (R-Ellensburg) said in a news release Wednesday, according to the Yakima Herald. But don’t get too worried: a sister bill died in the senate earlier this week, and that House bill stands little chance of getting past the legislature, much less voters.

Upthegrove’s concerns about Constantine’s sales tax proposal would dissipate in a Washington that had or at least allowed graduated income taxes. Seattle has a chance to precipitate a revolution in Washington state’s tax structure. Whether or not leaders here, in our self-styled center of Resistance against the Trump administration, seize that chance remains to be seen.

cjaywork@seattleweekly.com