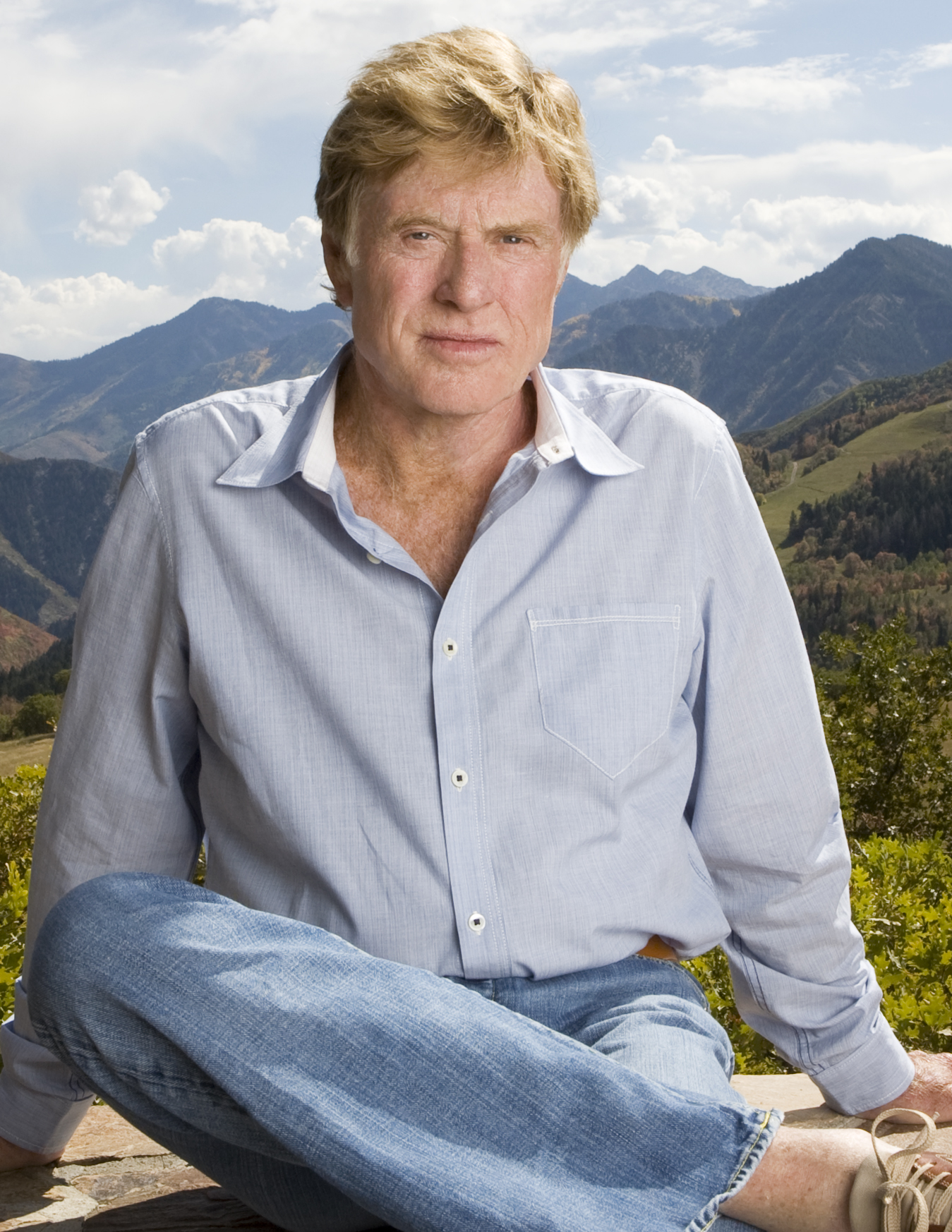

Like any director, Robert Redford has had to endure early rough-cut screenings of his movies, most recently The Company You Keep, with ordinary viewers in dreary suburban multiplexes. “When I was previewing my films, I had to suffer through all the trailers, all the ads. I thought, ‘Why couldn’t we go back to that concept I experienced as a kid?’ ”—in other words, the movie palaces of his youth, built during Hollywood’s pre-TV heyday. Going to movies was an event, he recalls: newsreels, shorts, and a double feature. “Growing up in L.A. as a kid at the end of the Second World War, my family didn’t have a lot of money, we didn’t have a car. We’d walk to the theater and see a show.”

Redford is calling to chat about this Friday’s formal opening of the Sundance Cinemas, formerly the Landmark Metro in the U District, which has been renovated in stages since last year, when Sundance acquired the lease. The cinema, the fifth built or purchased by Redford and partners since 2006, follows a different business plan than the megaplexes surrounded by parking lots and catering to teens (think Thornton Place or the Alderwood 16).

With ticket sales and revenues essentially flat, Hollywood is in a tough struggle with giant home TV sets, Netflix, Amazon, streaming, and so forth. Movie exhibitors make much of their money from popcorn and soda; and they, unlike studios, don’t get a share of video sales. For that reason, the now 21-and-over Sundance is offering a premium model of moviegoing, with booze, nicer food, and more amenities.

Sundance isn’t the only player in this market sector. Local venues including iPic, Cinebarre, Big Picture, and Central Cinema have been adding food and booze to the filmgoing experience. Even the nonprofit Northwest Film Forum now serves beer and wine. But, along with iPic in Redmond (previously called Gold Class Cinemas), Sundance is going the most posh.

“All our theaters are a more grown-up experience,” says Sundance marketing VP Nancy Klasky Gribler during a recent visit to the cinema (then still under construction). What she means are older and more affluent filmgoers who’ll pay more for seats reserved via the computer at home, where they can print their tickets. (You can also buy tickets by smartphone or walk in off the street.) Also: no ads before the trailers, and a full bar.

About that bar: By forgoing the under-21 crowd, Sundance is forfeiting tween hits like Twilight and profitable, long-running kid flicks like Despicable Me 2. In theory, it makes up the revenue gap with the booze, food, and a sliding-scale “amenity fee.” Matinees and early-week screenings will be cheaper (starting at $9.75); weekend shows will push your ticket to $15 ($18 for 3-D). I haven’t sampled the menu yet, but finger food like mini-pizzas, cheese plates, and a black-bean burger will run in the $8–$14 range. At the bar, drinks will range from $7–$11. And you can take your drinks with you into the 10 theaters, all of which have been handsomely refurbished.

Sundance now hardly resembles the charmless old Metro, which opened in 1989. Darker colors, new carpeting, accents made of recycled wood, local art on the walls, and furniture you can buy from Sundance’s retail arm—a considerable investment has been made in the place. (Landmark Theatres’ owner, Dallas billionaire Mark Cuban, could make that investment if he wanted, but he also unsuccessfully sought to sell the small national chain in 2011.) The projection room is now fully digital, though two old 35 mm projectors remain for special presentations. All the theater floors have been regraded for better sight lines, aisles are wider, and the new seating is much comfier.

By comparison, though I and most local filmgoers still have warm feelings about other Landmark properties—including the Harvard Exit, Guild 45th, and Seven Gables—their seats have grown threadbare and their carpeting faded. Landmark has gradually been shrinking its presence in Seattle. Last month’s closure of the Egyptian follows the fate of the Neptune—where I once shared the balcony with a rat—and the old Broadway Market.

Gribler estimates that Sundance now has about 85 percent of the Metro’s former seating capacity. The feeling is much less cramped—like flying business class instead of coach. Again, the Sundance business model is fewer customers but more revenue per customer. I haven’t sat through a movie there yet, but the digital projection and sound quality were excellent for a trailer I watched. Another improvement, Gribler promises, will be the parking discount ($2 after 5 p.m.). Unlike the Metro’s old scheme, you won’t have to return to your car before the movie.

As for Redford, he won’t be here for the grand opening, but he claims an affinity for our region: “I’ve always loved Seattle and its vibrant community. I’ve sailed around Puget Sound.”

When I mention how Lynn Shelton, our most prominent director, had her first great success at the Sundance Film Festival with Humpday in 2009, Redford brightens. Speaking of all his Sundance enterprises, he says, “That’s the whole point of it all . . . those kind of filmmakers. She’s an excellent example.”

bmiller@seattleweekly.com

SUNDANCE CINEMAS 4500 Ninth Ave. N.E., 633-0059, sundancecinemas.com.