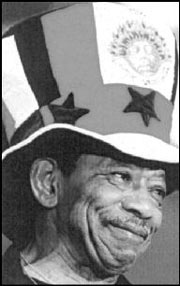

FOR HIS FINAL Hendrix experience, Al wore a gray cardigan, white carnation, and a mortician’s idea of a contented smile. Jimi came in a purple haze.

The father’s open coffin was draped with an American flag, and over it his dead son sang:

“You can hear happiness staggering on down the street/footsteps dressed in red.”

As in life, they were locked in death: Al Hendrix, 83, the footloose landscaper-turned-music-mogul who died of congestive heart failure April 17, and son Jimi Hendrix, 27, the Seattle rock icon who died 32 years ago from a drug overdose.

A young couple said they came to the funeral on Saturday because they loved Jimi’s inventive music. The others came because they loved Al.

Some of his flower arrangements were from MCA Records and the Rock + Roll Hall of Fame. They honored his son’s legend as well.

Al’s words on the day before he died—”I just want to say hello and goodbye and head on down the road and see what’s on the other side”—were printed in the memorial program.

Jimi’s words, written on the day before he died (Sept. 18, 1970), were also in the program: “The story of life is quicker than the wink of an eye. The story of life is hello and goodbye, until we meet again.”

For an hour, 300 friends and family members filled the pews at Mount Zion Baptist church on 19th Avenue, celebrating Al, hearing Jimi, and watching the lives of both flash past in a video montage.

Standing in the back of the chapel, sculptor Jeff Day spoke in a whisper between songs and eulogies. “Al commissioned me to do a bust of Jimi in the mid-’70s. When I brought it over one day, he burst into tears. He had me go get some vodka and a bucket of the Colonel’s, and we sat around and he told Jimi stories. He was proud and regretful. After a while, he took me into Jimi’s room. It had all his stuff in it—his clothes, guitars, a pack of Marlboros next to the bed. This was four, five years after he died, and Al still kept it like Jimi was just gone for the day.”

They were closer at the end than the beginning. Jimi was born in 1942 just after Al left for war. Father didn’t meet son until 1945, when Al came home to a marriage with Lucille Jeter that was already breaking up. Al was mostly absent, and Lucille drank herself to death. Jimi and brother Leon spent part of their childhoods in foster homes. A blues fan, Al later got little Jimi a cheap uke, then a guitar, which the boy learned to play behind his back and with his teeth; Jimi went on to become Garfield High School’s most legendary dropout.

Al remarried in 1966 to June Fujita and adopted her daughter Janie. Jimi died in London four years later. June died of cancer in 1999 (they played Jimi’s “Foxy Lady” at her funeral). Al wrested control of Jimi’s musical estate, which Janie runs. Experience Hendrix sells 600 licensed products today. Jimi, popular in life, is huge in death.

Al’s world seemed a happy one as the video played: smiling, posing, goofing off. There he is with the two wives he outlived and the child he wasn’t supposed to; with the family in the lean years and at the bumper of a Rolls in the honey days; with Jimi; then with just Jimi’s memorabilia. Oh, there’s Al with the grandkids. One is named Jimi.

Another is Austin, 15. He got up after the tape ended and went to a microphone. “To some people, he was known as grandpa, uncle, dad, Mr. H, Mr. Hendrix, Jimi’s dad, Al,” Austin says. “But to me, he was known as just my hero.”

There was polite applause and Mount Zion’s pastor emeritus, the Rev. Samuel McKinney, said some final words for Al. So did Jimi, as the music rose:

“A broom is drearily sweeping up the broken pieces of yesterday’s life. . . . “

Al was borne to the hearse, then to Renton. He was buried at Greenwood Cemetery. So was Jimi.