It’s a new conundrum for veteran tech executive Michael Schutzler.

The problem he’s facing involves something called a “smart gun,” an interesting new kind of weapon that proponents say could improve firearm safety. The gun will fire for rightful users, but for everybody else —including children and intruders—it would be useless. This is not a pie-in-the-sky idea. A handful of manufactures have come up with various models, some using biometrics like fingerprint identification, others radio-frequency technology. And yet, Schutzler marvels, “Nobody’s selling the stuff!”

At first, he couldn’t understand why. As he puts it, “Why is this complicated?”

As he has come to find out, there are a lot of reasons. Smart guns are not your typical technology product, but rather the latest flashpoint in the gun-control war. That means inflamed passions on both sides, at times devolving into death threats. Even on the same side, smart guns prompt disagreement.

So when the gun-control group Washington CeaseFire recently approached Schutzler, who serves as CEO of the Washington Technology Industry Association, to suggest that the two organizations co-host a symposium on smart guns, he eagerly agreed. “Let’s have all the people in a room and hear it out,” Schutzler says. That, he adds, was bound to be way more interesting than “yet another conference on application programmatic interfaces” or some other such topic routinely hashed over by techies.

The symposium, to be held today, Wednesday, Jan. 28, will be the largest gathering of its kind to date, according to Washington CeaseFire president Ralph Fascitelli. One smart-gun manufacturer, Robert McNamara of TriggerSmart, is flying in from Ireland to attend. Others are coming from around the U.S. Smart-gun critic Rick Patterson, from the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute, will share the stage with proponents. Also in attendance will be New Jersey state Sen. Loretta Weinberg, the author of a smart-gun mandate that’s turned her state into ground zero in the smart-gun debate.

Weinberg is now saying that she may work to repeal that mandate if she can get assurances from gun-rights leaders that they will work to end calls for a smart-gun boycott by firearms stores. Speaking to Seattle Weekly last week, she said she’ll be looking to gauge the temperature at the symposium, as well as to see whether the technology crowd here is interested in furthering smart-gun development.

Meanwhile, Fascitelli is trying to raise attention about a technology that he calls “as exciting an opportunity as exists” in the work CeaseFire has been doing for 30 years. Over coffee in Pioneer Square last week, he explained that he and others in the group have turned to technology after giving up on the legislative route. Yes, the state just passed landmark background-check Initiative 594, putting Washington in the forefront of the gun-control movement. But that, he says, was accomplished only after wealthy venture capitalist and do-gooder Nick Hanauer put his clout and money into the campaign. “We can’t count on $10 million to be raised for another ballot initiative,” Fascitelli says, referring to the sum donated by Hanauer, together with other big-name contributors like Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer.

That means gun-control advocates would be back trying to get legislation passed in Olympia, a route both futile and unpleasant, in Fascitelli’s mind. Of the crowds that show up at hearings on the issue, he says, “We would testify and there’d be 400 people with assault rifles yelling at us.”

Does more need to be done after the passage of I-594? Fascitelli and others in the gun-control movement say yes. Background checks only prevent criminals and others judged to be dangerous from buying guns. But they do nothing to stop a legally purchased gun from falling into the wrong hands—perhaps those of a child. Witness the Marysville Pilchuck High School massacre last October, carried out by a teen using a family member’s gun. Or look at what happened just a month later, when a Lake Stevens 3-year-old apparently found his father’s gun and shot himself in the face.

Smart guns, Fascitelli says, “could have prevented Marysville. They could have prevented Lake Stevens.”

Alan Gottlieb, founder of Bellevue’s Second Amendment Foundation, voices skepticism. “The problem is they’re not really smart. There are technical problems.”

Asked what evidence he’s relying on, Gottlieb talks generally about the use of biometrics. “I’m talking to you on an iPhone 6,” he says referring to a smartphone model that offers fingerprint identification as an alternative to a password. Most of the time it works just fine. However, he says, “One out of 30 times, my fingerprints don’t work and I need to put in my code.” If he were facing an intruder and needed his gun for self-defense, he says, such fumbling could prove disastrous.

As proof that smart guns don’t work, Gottlieb says we need look no further than law enforcement and the military, neither of which have snapped up these guns, despite their potential value in preventing bad guys from grabbing and using the guns of officers and soldiers.

In fact, there isn’t really a smart gun for law enforcement and the military to buy—not yet. Most smart-gun models are still in the final stages of testing and development. Only one company, Germany’s Armatix, has produced a gun it has tried to sell in stores. That model, however, is a .22 caliber—nowhere near powerful enough for law enforcement or the military. The Seattle Police Department’s guns, for example, are typically .40 or .45 caliber, spokesperson Sean Whitcomb confirms.

That doesn’t rule out the possibility that the SPD would use more powerful smart guns under development, Whitcomb adds, noting that the department’s chief operating officer, Mike Wagers, plans to attend Wednesday’s conference.

The caliber issue, though, is minor compared to the storm that happened when Armatix tried to sell its new gun, known as the iP1, in U.S. stores last summer. One, Maryland’s Engage Armament, agreed to take some of the guns. “So many people are on the fence about gun ownership,” co-owner Andy Raymond explained on a now-famous video posted to YouTube. If there were a gun that prevented accidents, he thought, people might feel easier about the matter. “They would go out there and exercise their Second Amendment rights.” For the gun community at large, he said, “I thought it was a good thing.”

The gun community told him differently—barraging him with ugly Facebook posts, some containing death threats. Raymond was so worried that his store might be burned down that he spent the night there; that’s when he filmed the video, cigarette in hand, a bottle of what looks like whiskey by his side.

Despite his rationale, and despite his anger at the Second Amendment supporters who wanted to “prohibit” him from selling a gun—“How hypocritical is that?”—he announced he would not be selling the iP1.

What Raymond didn’t initially understand is that if he sold the gun, he would trigger New Jersey’s mandate, which says that once a smart gun appears on the market anywhere in the country, all guns sold in the state of New Jersey must be smart guns within 30 months.

Gun enthusiasts see the mandate as a backdoor form of gun control that would get rid of most guns on the market while making those still allowed more expensive. (The Armatrix gun costs roughly $1,800, several times the price of a regular handgun.)

The backlash is scaring away not only retailers, but also investment. Alan Boinus, CEO of the California-based smart-gun company Allied Biometrix, had that impression confirmed while spending several days last week at the Shooting, Hunting, and Outdoor Trade Show in Las Vegas, a big event attended by all the major players in the gun industry. Asked what kind of reception he got, Boinus answers indirectly: “The first and most important thing anyone can do is to get rid of the mandate law.” Boinus plans to attend the Seattle conference, so presumably he’ll tell Sen. Weinberg that. So might Fascitelli, who says Washington CeaseFire would also like to see the mandate repealed because of its counterproductive effect. “This is how complicated it is: We’re at odds with the Brady Campaign,” he says. A big and influential group, the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence sued the state of New Jersey last year to compel it to carry out the mandate.

Aside from airing political and legal questions around smart guns, the symposium is sure to delve into the various technologies used in them. This too is a complicated subject. Like any company, smart-gun manufacturers are given to spin as to why their product is allegedly superior to their competitors. “The beauty of our product, and where we distinguish ourselves, is that we are not restricted to one platform,” Boinus says.

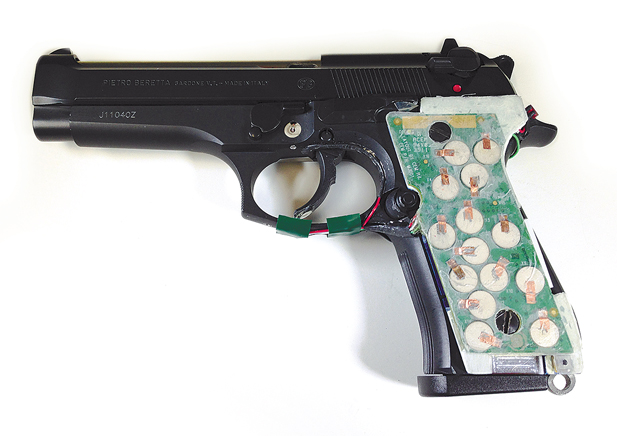

That product is not a gun per se, but a computerized grip that can be swapped out for the grip on any conventional gun. Boinus is working in partnership with the New Jersey Institute of Technology, a state university, which developed the technology. Donald Sebastian, head of research and development at the school, explains that researchers had a breakthrough moment when they figured out that an individual can be authenticated not just by a physical characteristic (in this case, the size of a hand) but by behavior (the way someone squeezes the grip). “Incredibly,” he says, it turns out that a person’s hand squeeze is unique, and the grip his school has developed can detect and analyze what he calls the “changing pressure pattern” of whoever attempts to use it.

That grip, which Sebastian says will come out in prototype form in a month or two, differs markedly from the Armatix product, which is an actual gun that works by radio frequency. The iP1 won’t shoot unless it is in close proximity to a wristband that is to be worn by the rightful user.

Both these models have their fans and critics, but Fascitelli says he is buoyed by poll results to be announced at the symposium. The poll, jointly commissioned by Washington CeaseFire and the San Francisco-based Smart Tech Challenges Foundation, found that 40 percent of interviewed gun owners said they would consider exchanging their conventional guns for smart guns.

Heck, even Second Amendment Foundation’s Gottlieb says he theoretically likes the idea. “If someone could come up with a smart gun that was reliable and workable, I would buy it tomorrow.”

nshapiro@seattleweekly.com