It shaped up as Timothy Dobbs’ perfect crime—relentlessly stalking and threatening to kill a former girlfriend who was left so shaken that, when it came time to prosecute him, she refused to go to court. He could have walked.

That’s a situation many domestic-violence victims face—fight or flight. Most, though, see the advantage of testifying against their abusers. As State Supreme Court Justice Susan Owens said last week, “Those in the best position to protect the survivors of domestic violence are the survivors themselves.”

The 31-year-old Dobbs, however, was convicted and sent to prison without the testimony of his frightened accuser. Cowlitz County Superior Court Judge James Stonier felt there was ample evidence from Longview police and other witnesses to convict Dobbs of six charges, including felony harassment, intimidating a witness, and drive-by shooting.

Which, it turns out, gave Dobbs a second shot at the perfect crime: He appealed, claiming that the absence of his victim—referred to in court as C.R.—was a violation of his Sixth Amendment right to confront witnesses against him.

It seemed an almost laughable legal ploy. He scares her speechless, then uses her silence to get out of prison?

Yet last week, three Washington State Supreme Court justices agreed with Dobbs. Though his tormented victim reasonably thought she could have died—“Last days . . . You fucked up and tripped with the wrong brother,” Dobbs told her in a 2009 death-threat note—they felt he deserved a second chance at trial.

They agreed with Dobbs’ appeals attorney, Eric Broman of Seattle, who argued that the trial judge made a “leap of logic” in concluding the victim didn’t appear because she was scared. “Courts can’t bend over backwards and allow the state to prove something it didn’t prove,” said Broman.

However, a majority of the Supremes felt otherwise. In an important 6-3 decision led by Justice Owens, they concluded that because Dobbs muted his victim by his violent acts, he forfeited his right to confront her. Though he never faced his accuser, he will remain locked up.

It’s presumably a popular, politically correct decision, one that also cites “common sense” as a basis. But did the high court follow its mandate to reach an unemotional interpretation of case law?

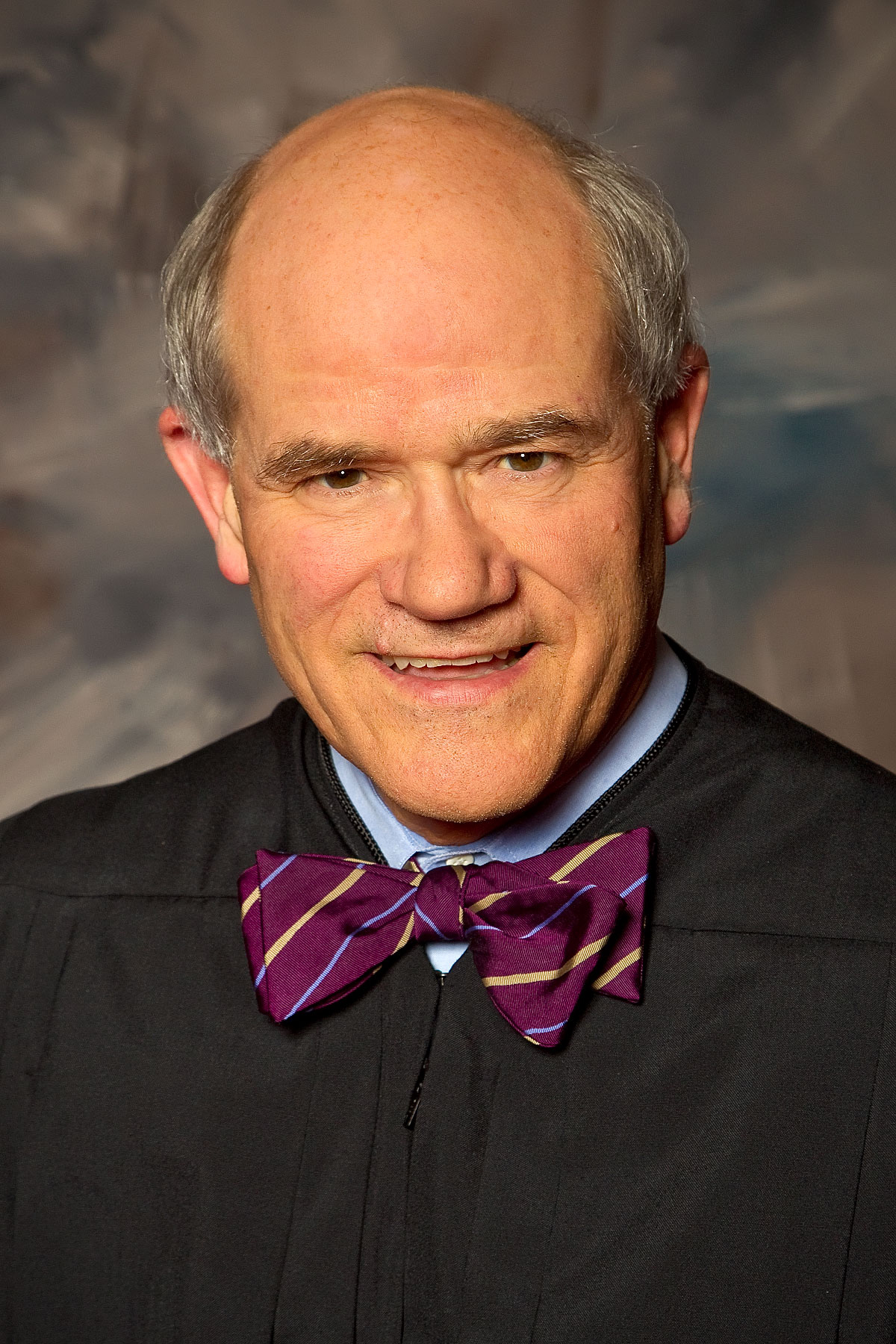

The three dissenters say no. They accuse the majority of making “an error . . . of a constitutional dimension,” as Justice Charles Wiggins, who wrote the dissent, describes it. He and fellow dissenters Justice Sheryl Gordon McCloud and Chief Justice Barbara Madden argue that “the majority overlooks the remarkable dearth of evidence connecting Dobbs’s actions to C.R.’s nonappearance.”

An earlier 2-1 appeals court decision upholding the conviction included a similar dissent, noting that “the record lacks even a scintilla of evidence” to explain why C. R. did not appear for trial.

That’s a key point. The law makes Sixth Amendment exceptions only when it is clearly and cogently shown that the accuser’s failure to appear was caused by the accused. Called the “forfeiture by wrongdoing doctrine,” it allows introduction of an absent witness’s testimony at trial.

To the majority, the “facts show that Dobbs was armed, consistently threatened C.R. if she cooperated with the police, and followed through on these threats by showing up at her house with a gun on multiple occasions, once even shooting at it,” wrote Owens in the majority opinion also signed by Justices Stephen Gonzalez, Mary Fairhurst, James Johnson, Charles Johnson, and Debra Stephens. “Any rational individual would fear testifying against such a person.”

The majority found it “highly probable” that Dobbs caused C.R.’s absence, conceding they lacked direct proof from the victim. “But that is the nature of the forfeiture by wrongdoing doctrine, where witnesses are scared into silence . . . We will not reward [Dobbs] for his success in bringing about that result.”

The Wiggins Three found that argument speculative. It’s “certainly possible” Dobbs frightened the victim into silence, they allow. “It is also quite possible that she had some other motive.” She may have decided she did not want him to be convicted, or had a dislike for law enforcement. Who knows? The record doesn’t say.

It does show the woman was contacted the night before trial by police and promised to appear, but vanished the next day. There’s no indication she was harmed.

In such situations, a judge “cannot conclude that the evidence of causation is clear, cogent, and convincing” as required, wrote Wiggins. As well, “The majority concludes somewhat implausibly that once behind bars, Dobbs somehow instilled such a fear in C.R. so as to prevent her from testifying at the very trial that would ensure her continued safety . . . ” At the least, felt Wiggins, prosecutors should be required to produce more evidence than was presented in this case.

“To a very significant degree,” says Seattle attorney Leonard Feldman, who analyzed the case for his law firm, “the issue turns on how best to balance the Sixth Amendment right to confrontation. That is plainly an issue on which reasonable jurists can (and did) disagree.”

randerson@seattleweekly.com

Rick Anderson writes about sex, crime, money, and politics, which tend to be the same thing.