“Each of us play a role in educating our children, and we need to be treated as professionals,” Phyllis Campano, Seattle Education Association (SEA) president, shouted into a microphone as she stood under John Stanford Center for Educational Excellence’s awning on Thursday.

Over 200 teachers and school employees represented by the SEA union donned shirts that read “Seattle Education Association,” forming a sea of red that stretched across the lawn. An array of signs, including some that asked for a “Fair Contract Now,” bobbed under the hazy sky.

“We know the legislators did not fully fund McCleary, but we do know they gave the district more money for competitive, professional salaries,” Campano told the crowd, listing off surrounding school districts including Lake Washington, Edmonds, Bellevue and South Kitsap that gave educators substantial wage increases in their recent bargaining agreements.

The first rally during SEA’s current contract negotiations with the Seattle Public Schools (SPS) was held shortly before the school board held a closed meeting at the John Stanford Center for Educational Excellence.

“We can make a little noise … to let [the school board] know that we’re ready for the fight,” Campano told Seattle Weekly at the close of the rally, music blaring overhead.

Educators voiced their desires for greater pay, more training and the rollout of an ethnic studies course throughout the district. Although the school district has yet to propose a new salary schedule, some teachers said they were prepared to go on strike if their demands weren’t met. Teachers staged the first system-wide strike in 30 years during the last bargaining session in 2015, when the union and district disagreed over pay. Stalled contract negotiations impacted over 50,000 students, causing parents to scramble for childcare.

“It’s up to the school board,” Campano told Seattle Weekly when asked about the likelihood of another strike.

The School Board declined to respond to inquiries during contract negotiations. SPS maintained that the bargaining team has been discussing compensation since June, and expects to continue negotiating wages through next week.

“Our staff are our heroes. They work incredibly hard every day supporting our students and families, and it is our job to support our staff as best we can. Our priority issue in negotiations is paying the very best salary to our educators and support staff that SPS can afford,” the SPS communications team wrote Seattle Weekly in an email. “We will work as hard as we possibly can, and be as transparent as possible, to assure that the new contract is concluded on time and provides the best compensation package we can afford and sustain. We know that any work stoppage hurts our students, our families, our community, and our staff.”

District employees are asking for higher wages after state Legislators infused $776 million in the school system this year to increase teacher salaries statewide to adjust for inflation from the previous school year and regional home prices. The funding was designed to help settle a nearly decade-long legal battle called the McCleary decision, after the state Supreme Court found in 2012 that the state was underfunding K-12 basic education.

In an effort to end the state’s reliance on local property taxes to fund basic education, the McCleary decision only allows districts to levy a maximum of $1.50 per $1,000 of the assessed property value in the school district or $2,500 per pupil, whichever is of lesser value.

Along with the ruling came a change in the way that teachers are paid. The state once gave additional money to teachers with higher education and more experience, but now school districts must create their own teacher salary schedules. Uncertainty about the longevity of funding from the state has led districts statewide — over 200 of which are currently undergoing contract negotiations — to fret over the requirement to increase educators’ salaries.

In Seattle, the school district has claimed that a decrease in levy funding will create a budget shortfall that is projected to grow to $68.1 million in the 2021-2022 school year. As a result, SPS released a budget update earlier this month that warned of potential program and staff cuts after a one-time surplus from state and district savings of $45.5 million runs dry.

“Support of education is up to the Legislature. Like our educators, we are frustrated that we did not receive ample, full funding. Our educators deserve a competitive salary; our students deserve great, well compensated teachers; and the district deserves the ability to attract and retain caring, and effective educators,” SPS wrote in an email.

Educators at the rally considered the district’s claims of a projected budget shortfall as an excuse to not offer competitive wages. Sophie Pritchard, a special education teacher at Jane Addams Middle School, has taught in Washington schools for nearly three decades and said that she can no longer afford rent in Seattle. After renting an apartment in Queen Anne for over a decade, she had to move toward the Shoreline border in January.

“I hope that we can be competitive in our compensation package because I can’t afford to live in Seattle,” Pritchard said. She also asked that secretaries and office administrators get additional training and competitive salaries.

Tamar Coleman, a special education instructional assistant at Ingraham High School, craves the financial stability to purchase her own home one day, although it seems unattainable given rising housing costs and her current pay.

“A lot of times we have to pay for our own training, and that’s something that we need so our students will be supported within the classroom,” Coleman told Seattle Weekly. However, she noted that her salary doesn’t allow her to pay for the trainings needed to expand or refresh her skills. It often takes several months to be reimbursed for out-of-pocket expenses, she said, which is time and money that she can’t afford.

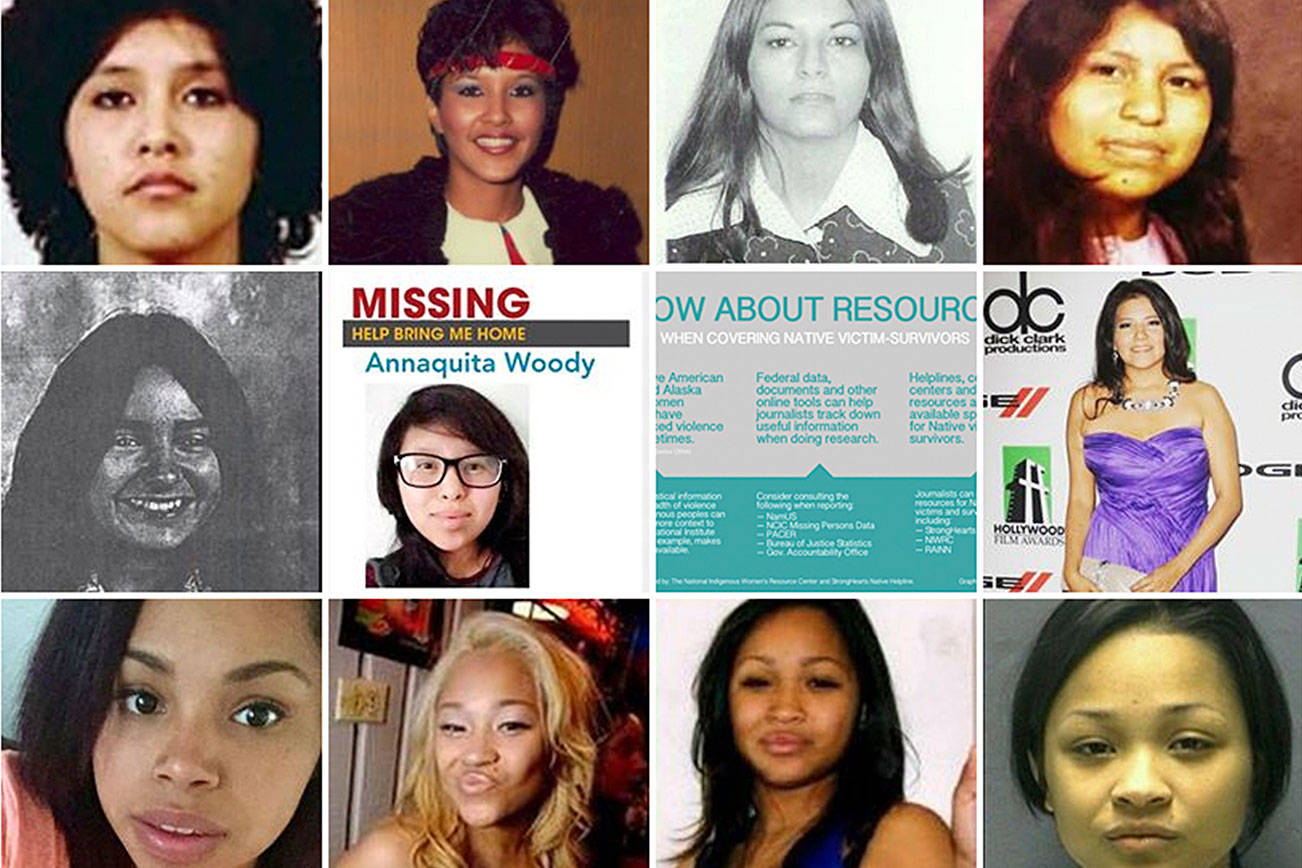

Speakers at Thursday’s rally spoke about the need to address Seattle’s racial achievement gaps — which a 2016 Stanford study showed had the fifth largest in the nation — by hiring and retaining more teachers of color. The racial disparities are also present in the district’s disciplinary practices, according to a 2017 SPS report, which revealed that the district’s 6th- to 12th-grade black students are suspended at seven times the rate of white and Asian students.

Jesse Hagopian, an ethnic studies teacher at Garfield High School, believes that the discussion of restorative justice practices and the rollout of an Ethnic Studies curriculum throughout the school district would address some of SPS’s racial inequities. Hagopian is teaching the first Ethnic Studies class in SPS, and hopes that the new contract will include the implementation of such a course in all Seattle schools.

“Ethnic Studies should be in every single building because every student has a right to learn about their own cultural history,” Hagopian said.

And he’s not hesitant to stall the negotiations to ensure that teachers are paid competitive wages and that marginalized students are granted greater resources. It’s of particular concern to him, as about 150 students at Garfield High School are experiencing homelessness, he said.

“I’m ready to go on strike again,” Hagopian concluded.

mhellmann@seattleweekly.com