The way Paul Lawrence described it, King County Superior Court Judge John R. Ruhl now has a $100 million question before him.

Lawrence, who is representing the city in its effort to defend an income tax on high-earners, reasoned to Ruhl during oral arguments Friday that he should side with the tax, since it would ultimately be looked at by the Supreme Court, as well. If the Supreme Court disagrees with Ruhl and strikes the law down, then per the ordinance passed by the City Council, all money paid to the city by high-earners would have it paid back to them, with interest. However, if Ruhl puts the law on hold only to have the Supreme Court rule it legal, then the city will have lost out on a year’s worth of tax revenue—estimated to come in at $140 million.

“The city will never get paid back if the law is put on hold,” Lawrence told Ruhl.

It shouldn’t be long before Lawrence knows if he gets his wish. While Ruhl made clear from the start of the hearing that he would not be handing down a ruling from the bench, he did say he planned to release his decision before Thanksgiving. He has plenty to consider in the case: He said that a total 1,210 pages were filed by various parities in the case—which has five groups of plaintiffs, the city, and the Economic Policy Institute acting as a amicus party on behalf of the city.

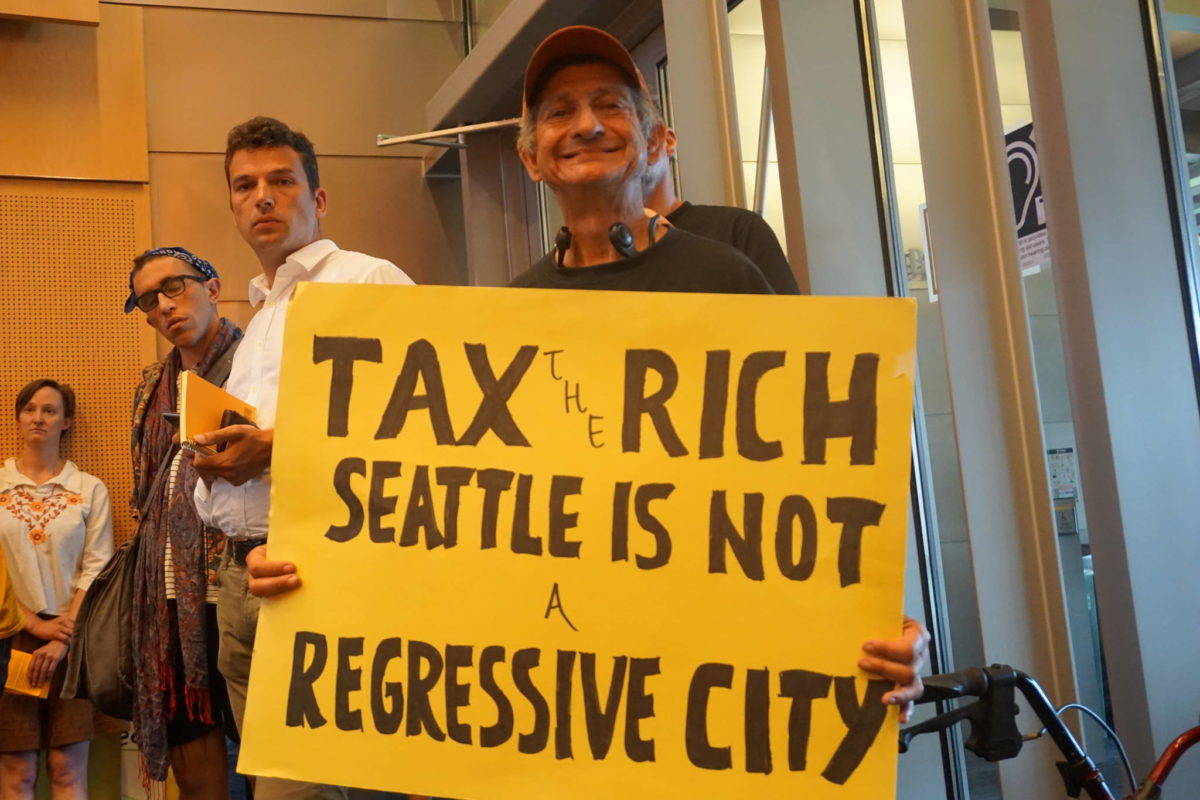

With all those filings, little was brought up in court Friday that hadn’t already been said in writing before; yet the proceedings nonetheless drew an overflow crowd to Ruhl’s small courtroom, with supporters of the tax pamphleteering in the hall and those who wanted to see the hearing packing a room in which it was live-streamed. Ruhl noted that the interest was warranted.

“I think this is a very, very important issue,” the judge said before adjuring, “and it deserves lots of attention.”

The three hours of arguments ranged from legal discourses drier than Black’s Law Dictionary to pugilistic.

Attorney Matthew Davis, who represents the lead plaintiff Michael Kunath in the case, used some of his allotted time to try to convince Ruhl to change course and rule against the city immediately.

“There are times that when the court rules is as important as how it rules,” Davis said. “Do everyone a service by sending a signal that this was not a close question.” Davis later drew some smirks, and groans, when he declared, “My malarky meter is broken!”

To the substance of the case, lawyers circled around the three major questions that have consumed debate over the tax, which would apply to income over $250,000 for individuals and $500,000 for couples: Is Seattle’s tax a tax on net or gross income; is income property; and does Seattle have the authority to pass this kind of tax in the first place.

Lawrence argued that, simply put, the city was establishing a tax on “the privilege, the benefit, of living in the city of Seattle.” While that might seem like a self-aggrandizing argument for the city to make, Lawrence says such taxes have precedence in Washington; for example, waste-management districts can charge everyone in their jurisdiction whether they use the servce or not, simply for the privilege of not living somewhere where trash is piled up everywhere.

“Although this has been a time of economic prosperity, it has caused hardships for the city,” he said. “Tax revenue is simply not keeping up with the needs of this city.”

Conversely, building off Davis’ point, lawyers representing plaintiffs opposed to the tax argued that the state couldn’t have been more clear with both constitutional case law and legislation barring local and progressive income taxes. Among plaintiff lawyers appearing before Ruhl were former Attorney General Rob McKenna and former Justice Phil Talmudge.

McKenna argued that it would be wrong for the courts to allow Seattle to enact a law when state voters have repeatedly rejected the idea.

“We think it does matter that voters four times have declined to change the constitution,” McKenna said.

Meanwhile, Kathy George, who represented the landlord group the Rental Housing Association, argued that it wouldn’t just be the rich paying the tax, in spite of rhetoric to the contrary. Specifically, she noted that people who sold their house in Seattle who have to report that as income in their federal taxes, and thus would pay the 2.25 percent tax on it.

“It’s not just wealthy people,” she said after the hearing. “If you’ve owned your home a long time in Seattle, you’re going to exceed that $250,000 threshold.”

Out in the hall, Pedro Espinoza with Carpenters Union Local 816, said he and other members turned out to remind people of the impact Seattle’s regressive tax system is having on workers—which would be relieved some by the city income tax.

“A lot of our members have been affected by tax increases, but you see these rich corporations and entities—they don’t get taxed enough.”

The tax, he said, “is in the interest of all working class communities.”

He said he thought the plaintiffs were making good arguments, but added that “in the end, you have to recognize what the reality is.

“The reality is what you are seeing, and in Seattle you are seeing more homelessness on the streets, drug issues—these issues aren’t being addressed. Instead we are squabbling over whether we can tax people who make over $250,000 a year.”

news@seattleweekly.com