Every day, Caitlin Vincent opens her doors to youth who have been exploited, taken advantage of, and made to believe that they were asking for it when they were sexually assaulted. She works as a therapist with Project 360, a King County Sexual Assault Resource Center program aimed at serving homeless youth 13-25 impacted by sexual assault. “They just feel completely disempowered and marginalized by society,” says Vincent.

Project 360’s services are one of a kind in Seattle—a fact that illuminates the huge gap in services that exist for homeless victims of sexual assault.

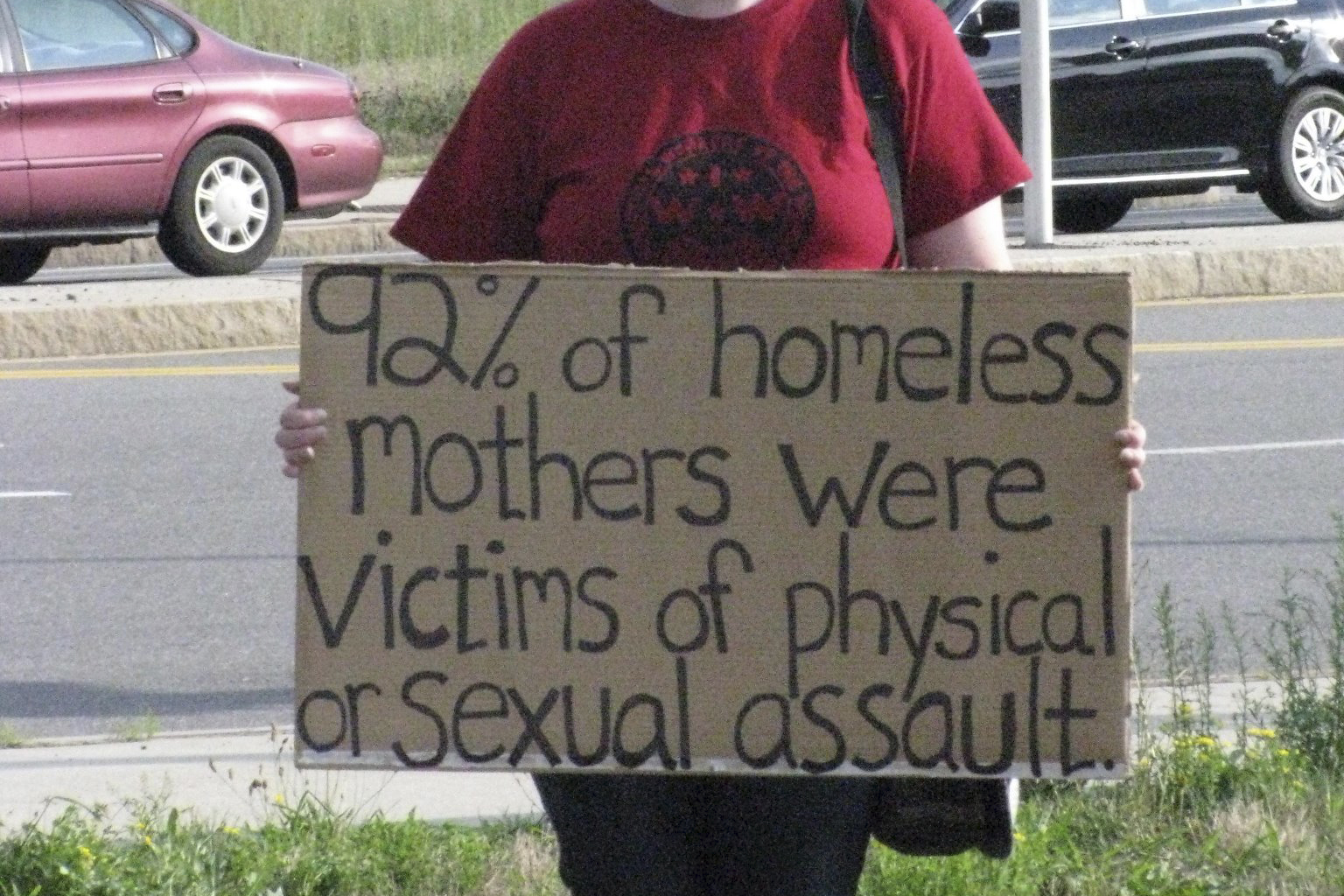

Sexual assault has a disturbingly strong correlation with homelessness. In her experience working with youth, Vincent says that many victims of sexual assault name it as the primary cause of their homelessness. Emily Gassert, another therapist with Project 360, says that in her experience 80-90 percent of homeless youth are victims of sexual assault. The National Network to End Domestic Violence reports that more than 90 percent of women who are homeless have experienced severe physical or sexual abuse at some point in their lives.

The correlation flows both ways. While sexual assault is often a cause for homelessness, homelessness is also a risk factor for revictimization.

“The condition of homelessness itself dramatically increases women’s risk of being sexually assaulted,” states a study by the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence. “Women on the streets do not enjoy the same degree of safety as women who have four walls and a roof to protect them.” Additionally, shelters are often located within or near high-crime areas, heightening the risk of sexual assault.

To add to this, Vincent says that the symptoms of PTSD resulting from these traumas often keep individuals experiencing homelessness from taking advantage of the resources right in front of them and seeking employment.

“Getting a job where a male authority figure reminds them of instances that bring back memories of the assault it detrimental,” says DeAnn Yamamoto, Deputy Executive Director of the King County Sexual Assault Resource center. “They might fall apart or withdraw. It will make them unsuccessful at work.”

A viscous cycle is created–sexual assault is one of the leading causes of homelessness, homelessness is then a huge risk factor for revictimization, and the PTSD caused by these traumas prevents individuals from accessing resources available to them or maintaining stable jobs.

Yet, experts say sexual assault treatment for homeless women is lacking, in large part because sexual assault treatment programs have not been designed with homeless women in mind.

“There’s always been this belief that you really can’t participate in trauma-specific services unless you are living in a stable condition because talking about traumatic instances requires a lot of interpersonal resources,” says Yamamoto.

Individuals experiencing homelessness live far from a state of stability. It’s not uncommon for someone to begin therapy at a mental health clinic and then be kicked out or waitlisted due to sporadic attendance, says Yamamoto.

Missing appointments is often not a conscious choice, says Vincent. There are many factors that create barriers between individuals experiencing homelessness and the care they need. Not surprisingly, folks prioritize survival over treatment. “Much of homelessness is spent maintaining life on the street,” says Yamamoto. If they’re looking for a job, an interview trumps therapy any day of the week.

Despite the barriers, Project 360 has seen huge improvements in the lives of their clients. The process takes longer because of clients’ sporadic schedules, but clinical success for those experiencing homelessness is on par with those who aren’t, says Yamamoto.

Yet Project 360 limited to two locations and the ages of 13-25, and there is general agreement that the sexual assault element of homelessness is under-addressed in Seattle.

“The longer someone is on the streets the more vulnerable they are, the more likely it is for sexual assault to happen again and again…,” says Vincent. “Giving them trauma-specific therapy to address PTSD symptoms, in tandem with other services for full-circle care, will support their continued success.”