“My name is Lorraine Netherton,” said the voice on the phone to a King County Sheriff’s Office 911 operator. “One of the women I’m with, her ex showed up at her child’s school and took her.”

At around 3:35 p.m. on Nov. 23, 2002, Netherton said she was in a car in Ravensdale, located in rural east King County, and identified herself as the former director of the Federal Way Domestic Violence Task Force. She and the child’s mother were parked outside a home where they suspected the father was with the 7-year-old. He was in violation of a court order giving the mother custody, Netherton explained. A trailer was in the driveway.

“We think they’re going to leave with the child in this trailer,” said Netherton.

The operator took detailed information and said an officer would be dispatched.

“Thank you,” Netherton said. “I love you.”

After five minutes, according to 911 recordings from that day, the operator called back to say an officer was on the way. Another few minutes passed before Netherton called 911 again and spoke with a different operator. Netherton reiterated the situation, adding, “It looks like they’re trying to leave.”

The operator couldn’t say when an officer would arrive. Within five minutes came another 911 call.”This is Lorraine Netherton! I’m going north on Southeast 268th. The subject just left…” The operator had trouble hearing the call as Netherton’s cell phone cut out. “This man kidnapped his daughter…he took the child from school yesterday… God…they’re trying to lose us!”

Netherton’s voice rises. “They’re out of the car!” she shouts. There’s a commotion, and the sound of feet on the ground. “He kidnapped that kid!” she says to someone. And, seemingly to someone else, she commands: “Don’t you fucking leave!”

“Hello?” says the operator. “Hello?” No answer.

Minutes later, at 3:54 p.m., a caller is back on the line. “Shots fired! Woman down, 26723 Southeast Ravensdale Road!”

The excited caller gulps deep breaths between words, and is partially inaudible. “She…opened the car door and attacked me and [inaudible] pounding the hell out of me and I [inaudible] in the blackberry bushes, and I fired.”

“You fired?” asked the operator.

“Yes!”

“What’s your last name?”

“Netherton!”

This time, units were on the way. When they arrived, officers found 22-year-old Desiere Rose Rants dead in an alley, and Lorraine Netherton standing nearby with a silver gun. She had tried to get police help, she told officers. But it all went sideways—she was attacked and had to shoot in self-defense.

Today, seven years later, Lorraine Netherton is still trying to prove that’s true.

Now 47, Netherton is a quarter of the way through a 23-year term at the state women’s prison in Purdy for murdering Rants, who’d been helping her brother and his child. She and Netherton met for the first time that November day in the valley, and Rants fell dead with two bullets in her stomach and chest.

Netherton insists she was wrongly convicted, something that leaves prosecutors arching their eyebrows and pointing to the court record. Evidence and testimony at a three-week trial persuaded a jury, after two days of deliberation, to find her guilty of murder. The verdict is now on its second appeal, according to her Seattle attorney, Tim Ford. In one of his recently filed briefs, Netherton says, “When I fired the shots that killed Desiere Rants, it was not my intention to kill her. My only intent was to stop a violent assault by her.” The latest appeal is now before the state Supreme Court in Olympia, after a lower court twice confirmed that she’d gotten a fair trial.

Netherton has at least one true believer, however: one of her three former husbands. Rich Laxton of Seattle has spent much of his time and a lot of his money to help the combative woman he divorced two decades ago. Despite their breakup, says Laxton, “I decided I was not going to let Lorraine rot in prison for 23 years. If I believed she was guilty, I would have walked away. She’s not.”

Even after paying more than $100,000 in legal fees, the West Seattle machine-shop programmer is undaunted by the case’s unblemished losing streak. He undertook his own investigation to disprove compelling testimony and evidence. Netherton was, after all, the woman he once shared his life with—and would do so again.

“I still care for Lorraine, and if her case is overturned, I would consider getting back together if she wanted to,” Laxton says. “Even after we were divorced, we went on occasional river-fishing trips, travels to Ocean Shores, and other outback adventures. People change with time.”

But it was mostly, he says, a sense of justice that trumped a bad breakup and his ex’s reputation as someone who wouldn’t win anyone’s popularity contest.

“She’s got a temper,” he says, leaving it at that.

She’s also got a penchant for bringing a gun to a fistfight, starting with the other time she shot someone.

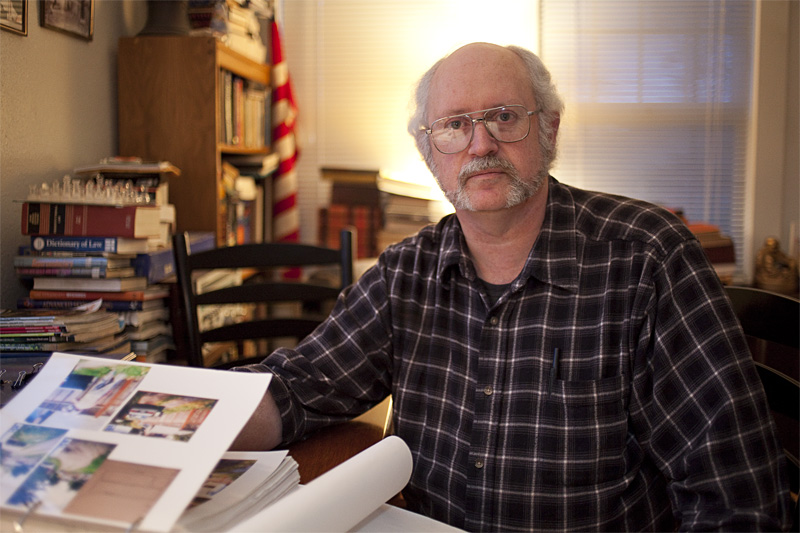

Laxton is scrolling down a catalog of folders and files on the computer screen at his West Seattle home. “Here it is,” he says, opening a cache of court documents and crime photos from the Rants murder scene.

Behind him, draped over an unused fish tank in his front room, are large, neat crime-scene charts. On the desk is a stack of files and crime-scene CDs. He figures he’s spent roughly “hundreds of hours” going through the material, collecting new data, and feeding much of it into his computer.

“They said she shot Desiere while she was on the ground,” says the trimly bearded Laxton, 54, slightly balding with graying hair. He adjusts his glasses and taps the keyboard. “It couldn’t have happened that way.” He finally has the evidence, he thinks, to prove his former wife is no murderer.

One of their three sons moves around in the kitchen of Laxton’s small High Point home. Two of them—all are in their late 20s—live with Laxton. Netherton has seven children altogether, starting with her 1979–84 marriage to Laxton. He has memories of good days mixed with bad nights, but doesn’t say much when asked what went wrong, other than mentioning it got “volatile” at the end. (Court records state Netherton accused Laxton of domestic violence, claiming he broke her nose, which he denied.)

They stayed in touch through the kids and support checks, he says. But essentially, “She went her way, I went mine.”

Netherton’s way led her to bed down with a series of badges. She dated a Seattle cop and had a son with him, according to court records. In the 1990s she married and divorced a state prison corrections officer, then married and divorced a security guard. In court, the men told similar stories about her temper and a tendency to throw household furniture.

She also carried a .44 magnum in her purse.

On March 23, 1988, Netherton shot a man named Theodore Chomin outside a West Seattle bar. She got angry when he tried to help her put on her jacket, Chomin told police. She fired several shots, Chomin claimed, one of which struck him in the abdomen. He was hospitalized, but survived.

Netherton, then known as Lorraine Laxton, told a much different story. Chomin had beaten her and pushed her off her feet, and she fired one shot in self-defense. Police investigators said they determined she fired more than once, and concluded, according to public documents, that “the number of shots was particularly excessive, given that Mr. Chomin was unarmed.” (Chomin couldn’t be reached for comment.) Police recommended a charge of assault or attempted murder, but prosecutors disagreed, feeling they couldn’t disprove Netherton’s self-defense claim, and she was never charged.

Netherton eventually moved into a Federal Way mobile-home park, where she lived with some of her children. According to court records, the local police were frequent visitors to her trailer. “Many of these complaints,” wrote prosecutors in a memorandum on Netherton’s background, “were generated by her children’s teachers at school, who reported that the children were physically and emotionally neglected.”

In 2000, Netherton revived the moribund Federal Way Coalition Against Domestic Violence, and appointed herself chair. In court, she’d later explain she got involved “because of my own experience as a victim of physical abuse and domestic violence, which was extensive.” Concerns soon surfaced about her temper, court records show, and about her handgun, which once fell out of her purse during a Coalition event at a local grocery store. Within two years, Netherton was voted out as chair at a meeting at which an armed police officer was brought in for security.

It’s not exactly a warm portrait of a wife and mother, Rich Laxton allows. But that doesn’t change the evidence he has dug up to support her self-defense claim in Rants’ killing, he says.

On his computer, Laxton brings up crime photos and points to a bent, possibly broken finger on the deceased Rants’ left hand and abrasions on her other hand. At the trial, experts testified they had found no real indications that Rants had assaulted Netherton; Laxton thinks the pictures show otherwise. He also brings out prints of post-arrest CAT scans showing what could be a fracture of Netherton’s face, and says jail medical reports and inmate testimony show she had facial bruises indicative of a fight.

In a moment, Laxton is on his feet, going over the crime-scene drawings, highlighting the small space, between the car and a fence, in which the Ravensdale confrontation took place; tracing the ejection paths of Netherton’s gun shells; and noting apparent errors in crime-scene photos presented to the jury. At one point he bends over and leans against his living-room door.

“Here’s Lorraine, up against the fence, after Rants attacked her,” he says. “She [Netherton] fires the first shot, it goes into the car at an angle.”

Then he assumes the position he thought Rants was in. “The first bullet hit her here,” he says, pointing to his lower right abdomen. “The second here,” he adds, pointing to his upper right torso below the shoulder. “They say she [Rants] was on the ground when that shot was fired. By my calculations, she was standing and leaning, like this.”

He straightens up. “If Lorraine had shot Rants on the ground just below the clavicle, there would have been GSR [gunshot residue] all over the shoulder of Rants’ jacket, and there was none. And the shells could not possibly have landed six feet, 10 feet behind her and on the roof of the car on the passenger side, as they did.” At trial, experts said the rooftop shell had been ejected upward as Netherton intentionally swung the gun toward Rants, tilting it sideways, to fire the final shot.

Laxton returns to his desk chair and takes out tightly cropped jail photos of his ex’s face. Over what could be injuries to her brow and nose, he has written “Turning color” and “Fracture.” The injuries are barely perceptible, so he has drawn arrows pointing to them.

He gazes at the shapely woman with long ash-blonde hair, big eyes, and high cheekbones who made him unhappy 25 years ago. That doesn’t matter now. Besides calls to attorneys and prosecutors and the courts, he pesters newspapers and TV stations, hoping to interest them in the injustice. No one wants to hear his tale of Netherton: “‘She was convicted, end of story,’ they say,” Laxton laments. But he carries on because no one else will.

“The legal system let Lorraine down,” he adds. “If you listen to the 911 audio tapes, Lorraine sounds pretty composed to me—not at all like some hot-headed vigilante like they claim. She has a temper, but that did not come into play there.” Some investigators, he feels, “seemed to be more interested in slinging mud at Lorraine than figuring out what really happened at the crime scene. I feel like I’m doing the job they didn’t do.”

Desiere Rants, a pretty, oval-faced blonde, was unemployed and living with friends—babysitting to help them out—when she died of gunshot wounds in the alley behind her Ravensdale residence. According to witnesses, police reports, court records, and interviews, her killer, Netherton, was helping a trailer-park neighbor, Gwen Rees, regain custody of the 7-year-old child she’d had with William (Willie) Rants, Desiere’s brother.

Willie Rants, who has a long misdemeanor record, had recently completed probation on a federal conviction for possession of marijuana. Court records show that Rees, who had recently split with Rants, also had drug issues, but was in rehabilitation, and had demonstrated to a King County judge that Rants was an unfit parent, gaining temporary custody of their child. Around the same time, Rants obtained a court order from the Puyallup Tribe of Indians, of which he’s a member, giving him temporary custody.

Willie Rants then picked up his daughter at her Federal Way school on Nov. 22, 2002. When Rees discovered her child was taken, she got in touch with Netherton, who felt the tribal order was invalid and said she’d help Rees find Rants and recover the child.

They first called Tacoma police, informed them of the case and their court order, and asked for assistance. Officers met them at two locations in Tacoma that day, where Rees and Netherton thought Rants and the child were, but neither hunch panned out. During the long night and early morning, Rees and Netherton checked other locations on their own, including Desiere Rants’ residence in Ravensdale.

According to Rees’ friend Mandy Cunnington, when Rees and Netherton visited Cunnington’s home around 3 a.m. on Nov. 23, Rees showed the friend a gun she was carrying and said, “This time, I’m gonna kill him [Rants].” According to Cunnington, Netherton then added: “If she doesn’t, I will.”

By that afternoon, Rees and Netherton, along with Rees’ boyfriend, Barry Phares, and another friend, Shannon Cauthorn, were sitting in Phares’ Thunderbird outside Desiere Rants’ home. That’s when Netherton made her first 911 call to the King County Sheriff’s Office, advising the operator of the situation and requesting that a car be dispatched to help—as Tacoma police had done before.

After two more 911 exchanges, Netherton saw Desiere Rants drive by in her Kia with Willie and the child. Netherton and her posse gave chase. From the front passenger seat of the T-Bird, Netherton then made her breathless 911 call: “This is Lorraine Netherton! I’m going north on Southeast 268th…”

The high-speed chase led down several streets and around sharp curves. The two cars ended up in a grass-and-gravel alley behind Desiere’s house. Willie quickly bailed with the child, disappearing behind a high fence. Netherton scrambled from the T-Bird as Phares, with Rees and Cauthorn, drove around to the front of the house to head off Willie. Netherton walked down the alley, approaching Desiere—still at the wheel—on the driver’s side. Another child, whom Desiere was babysitting that day, was strapped into a rear car seat.

Netherton and Rants faced each other in a three-foot area between the car and fence. Within a minute, Rants was on the ground, dying. That’s when Netherton called 911 for the last time: “Shots fired! Woman down…” Says her attorney, Ford, “The crux of this case is what happened between those two calls.”

It was about that time that another call, from an apparent witness, came to a different 911 operator. “Um, Ravensdale! Somebody’s just been shot.” The caller gave the address, saying that a woman had been shot in the chest and that, from her backyard, she could see another woman standing nearby with a silver gun, talking on her cell phone. “God, how stupid and senseless people are!” the caller said.

The operator told her that units were on the way. The caller seemed to be talking to the shooter: “She was not! Yeah, I saw ya!” Then the caller spoke to the operator. “She says this girl was beating the hell out of her. She was not! She was just standing there.”

When police arrived, they found Rants lying next to the car and Netherton pacing behind the Kia. They confiscated her 9mm semi-automatic. She also turned over a second gun she’d brought along, a .44 magnum revolver.

Netherton told police that Desiere had attacked her as she walked up, hitting her repeatedly in the face. She pulled one of her handguns, she said, and struck Desiere in the face. That didn’t stop her, and she had to shoot to defend herself, Netherton claimed.

Homicide detectives arrived and began getting conflicting accounts from eyewitnesses. Two men said they saw Netherton walk down the alley, and one followed a few feet behind her to help after hearing Netherton exclaim, or so he thought, “He kidnapped my daughter!” He saw Netherton fire at Desiere, the first shot going into the left rear car door, passing just behind the toddler’s car seat.

Desiere, according to witnesses, patted her chest in apparent disbelief the shot had missed her. Netherton fired a second time, and Desiere went down; Netherton then drew closer and fired a third time as she collapsed. Altogether three witnesses told police that the shots seemed unprovoked. Lab tests later indicated that Netherton was at least four feet from Desiere when she fired the last shot.

In a recent brief filed to oppose Netherton’s appeal, King County prosecutors give this narrative of the scene, as recalled by one of the witnesses, Jerry Jacobs, who lived nearby:

“Netherton pushed Desiere back against the Kia, drew her 9mm, and fired from five or six feet away. Jacobs was only three or four feet away from Desiere when Netherton fired. After she was shot, Jacobs heard Desiere say, ‘What is this?’ Jacobs told Netherton, ‘You don’t have to do this.’ Netherton said nothing in reply, just turned the gun sideways and fired again, this time at Desiere’s midsection…Netherton walked off towards the front of a house. Jacobs and his brother, [Thomas] Bonifas, lifted Desiere and asked her where she was hit. She looked at them, shook hard, and then went limp.”

But Netherton insisted she’d been attacked. “This broad broke my nose,” she said to police of Desiere, whose family would later describe her in an obituary and public statements as a peaceful, single woman who loved children and dreamed of starting her own family. No family members could be reached for this story, but Desiere’s grandmother, Joyce Cross, told a reporter in 2002 that she “had a pretty, round face and eyes that kind of twinkled. She was one of those simple people that just loved everybody. She wouldn’t hurt a fly.” The family was obviously crushed: Desiere was murdered only hours after she and Willie returned from a funeral for their aunt that morning.

Netherton later claimed she had been struck in the face eight times by Desiere, causing her nearly to black out and become paralyzed (although witnesses saw no evidence of that). Regrettably, she had to shoot to save her own life, she said.

The circumstances were eerily reminiscent of the day Netherton shot Chomin outside the West Seattle pub. But this time, prosecutors not only didn’t believe it was self-defense, they felt it was first-degree murder. As in the pub incident, one shot might have been defensible. But the second and third bullets seemed like an execution, they said.

In July 2003, the jury partially agreed, opting to convict Netherton of second-degree murder. It wasn’t premeditated, they concluded. But it was murder.

Rich Laxton thumbs through a four-inch-thick stack of documents on his desk. They’re among the pounds of paper he retrieved from Netherton’s trial attorney, Phil Mahoney, several years back. As he began to read some of them, he became convinced his ex was wrongly convicted, launching his new spare-time career as crime sleuth.

“I just kept turning over more and more rocks, and got hooked,” he says.

Among his contentions, which are now part of Netherton’s appeal:

• Crime photos indicate Rants had a broken finger and damaged knuckles, which the jury never learned of, but are indicative of the fight that Netherton describes.

• Ejected shell locations show Netherton could not have shot Rants while Rants was down; rather, shots were fired from a close-in defensive position.

• CAT scans and X-rays from the next day show fractures and a large bump on the back of Netherton’s head, which were never pointed out or shown to the jury.

“Lorraine repeatedly called police for assistance,” says Laxton. “She didn’t just walk up and shoot someone for no reason. And there was no reason to do so other than she was being attacked.

“She told me she felt she was fighting for her life, and the witnesses couldn’t see that from their positions. Desiere knocked her down and kept coming even after [Netherton] hit her with the gun and fired the first time.” His ex had only a few pressured seconds to weigh her options, he argues, and her story never changed from the moment it happened.

But as prosecutors contended in court, she had the unarmed Rants at gunpoint, and had room to maneuver back down the alley. Netherton stayed in the zone and fired again and again—either body shot could have been the fatal one, the medical examiner said.

Laxton amassed much of his information after laying out $15,000 for Netherton’s failed 2004 appeal. He undertook more legwork, assembling a list of what he felt were questionable evidence and unethical prosecutorial practices, and engaged Ford to take the case. To date, Laxton says he’s paid about $110,000 in legal fees and still owes Ford’s firm about $27,000.

Netherton’s latest appeal was rejected in November by the state Court of Appeals. “A couple of the issues addressed in that [recent] appeal,” says Ford, “have some overlap with what was in Lorraine’s [original] direct appeal.” Now the state Supreme Court must decide if it will hear the case and if so, what issues it might consider for review.

Ford is asking the high court to send the case back to the appeals court for further study, contending the appellate court failed to fairly consider new mitigating evidence, described as “hundreds of pages of evidence that was not discovered or presented by trial counsel,” including photographs, X-rays, and expert witness declarations.

“I think we have as good a shot as any—the issues are strong and the handling of them by the Court of Appeals was, in my opinion at least, shoddy,” Ford says, emphasizing the historic difficulty of overturning guilty verdicts even when new evidence is discovered. “We have a pretty poor system for processing such [post-conviction] cases, and I don’t know if the Supreme Court realizes that or cares.” It’s possible, he says, he’ll end up taking the case to federal court.

In the current appeal, Ford contends that prosecutors displayed misconduct by dramatically telling jurors Netherton was not only armed with two guns, but that she was carrying enough ammunition to kill 40 people—or “three juries,” as a prosecutor put it in court, emphatically spilling a container of bullets across a table. Ford also raises the issue of effectiveness of Netherton’s trial lawyer, Mahoney. Among important evidence available but not submitted at trial, Ford claims, were records of Desiere Rants’ conviction for assaulting another woman and her failure to get court-ordered anger therapy, and “lengthy, plainly impeaching records of professional misconduct” by both a detective who gathered key evidence and a crime-lab expert who analyzed it. Defense counsel should have made more of conflicting trial testimony, Ford also contends, such as eyewitness statements that Netherton and Rants “collided” next to the car.

A longtime criminal-defense attorney, Mahoney handled the indigent Netherton’s case for $850, he says in a statement which he provided to the appeals court regarding his “ineffective assistance.” He in part blames “inadvertence” for his failure to obtain pictures of his client’s injuries, and never noticed whether the crime-scene video shown to the jury displayed any injuries to Rants’ hands. An investigator whom Mahoney hired did only limited pretrial probing of evidence and questioning of those involved, he states. As for the prosecutor’s comments about Netherton being capable of wiping out three juries, Mahoney says, “I do not recall that and do not recall any tactical reason for not objecting to that.”

Mahoney contends he did what he could for Netherton, whom he’d known for some time and who had once dated his son. Considering the small budget he had to work with, Mahoney says, “I do not believe that I was ineffective, and, after all, I was effective enough to persuade the jury to decide on second-degree rather than first-degree murder.”

For their part, prosecutors defend the “three juries” statement, noting in their appeals brief that under case law they have wide latitude in closing arguments to draw “reasonable inferences” from the evidence. Ian Goodhew, deputy chief of staff for King County Prosecutor Dan Satterberg, says that as far as they’re concerned, most of the issues have already been settled at trial or in the earlier appeal.

“We do not have any comment other than this matter was tried before a jury, a verdict was rendered, and it has been upheld on appeal,” says Goodhew. “We will continue to work on the matter if the appeals continue.”

And they will continue, says Laxton—as long as he can afford it. He’s already aching over the $122,000 he has drained from his IRA (not counting early-withdrawal fees) to pay for his ex-wife’s appeal.

But as nightfall comes, he is still at his desk, bringing up another screen of evidence and searching for loopholes. Flickering images of Rants’ face and Netherton’s appeal are reflected in his glasses. In Laxton’s living room, at least, both are still very much alive.