A bill that passed in the Washington State Legislature is aimed at simplifying the protection order petition process for victims of domestic violence, but while some barriers were addressed by the law, some advocates against domestic violence say that many still exist.

Sen. Manka Dhingra (D-Redmond), who sponsored the companion bill of HB 1320 which passed into law earlier this year, said domestic violence across the state has risen by 30% during the pandemic and domestic violence homicides have seen an uptick as well.

She said HB 1320 intends to increase the accessibility, efficiency and effectiveness of protection orders by consolidating several previously separate protection orders including: domestic violence, vulnerable adult, anti-harassment, sexual assault, stalking and extreme risk.

Dhingra said the new process will be “centered on a survivor and their safety.”

Previously, victims or other petitioners would have to undergo separate court processes depending on which protection order they were trying to receive, a complicated and often lengthy process that some have described as a legal patchwork that victims or advocates would have to navigate.

With such a previously lengthy and involved court petition process in which abuse survivors would basically have to make their own case for their protection, many factors could prove to be barriers to victims getting the sense of safety they deserve. Work, childcare and of course trauma could all stand in the way of a victim seeing the process through to the end, and of course there are more complicated obstacles than just those.

Sandra Shanahan is a victims advocate on the King County’s Victim Assistance Unit, which helps survivors of abuse navigate the legal system in order to get the proper protection against their abusers. She said language barriers, inconsistencies in the due process of the petition based on different jurisdictions and the exhaustion of the process have all been obstacles to protective justice.

“Survivors get washed out of the system,” Shanahan said. “Many never make it to the point where a judge could make a decision.”

Riddhi Mukhopadhyay, director of the Sexual Violence Law Center, spoke on a way that abusers can weaponize the court process against survivors, known as cross-petitioning. It is when an abuser that may know they are having a protection order petitioned against them will try to petition a protection order against the person they have abused as a way of framing the survivor as the perpetrator.

She said this technique can put true victims on the defensive and can confuse the court, ultimately obstructing survivors from the protection and justice they deserve.

“We don’t want courts to be perpetuating further abuse through the system,” said Mukhopadhyay.

Policy Director at the Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence, Grace Huang, pointed out that abusive litigation laws are currently on the books to help combat cross-petitioning, but also emphasized another barrier to victim protection from abusers; coercive control.

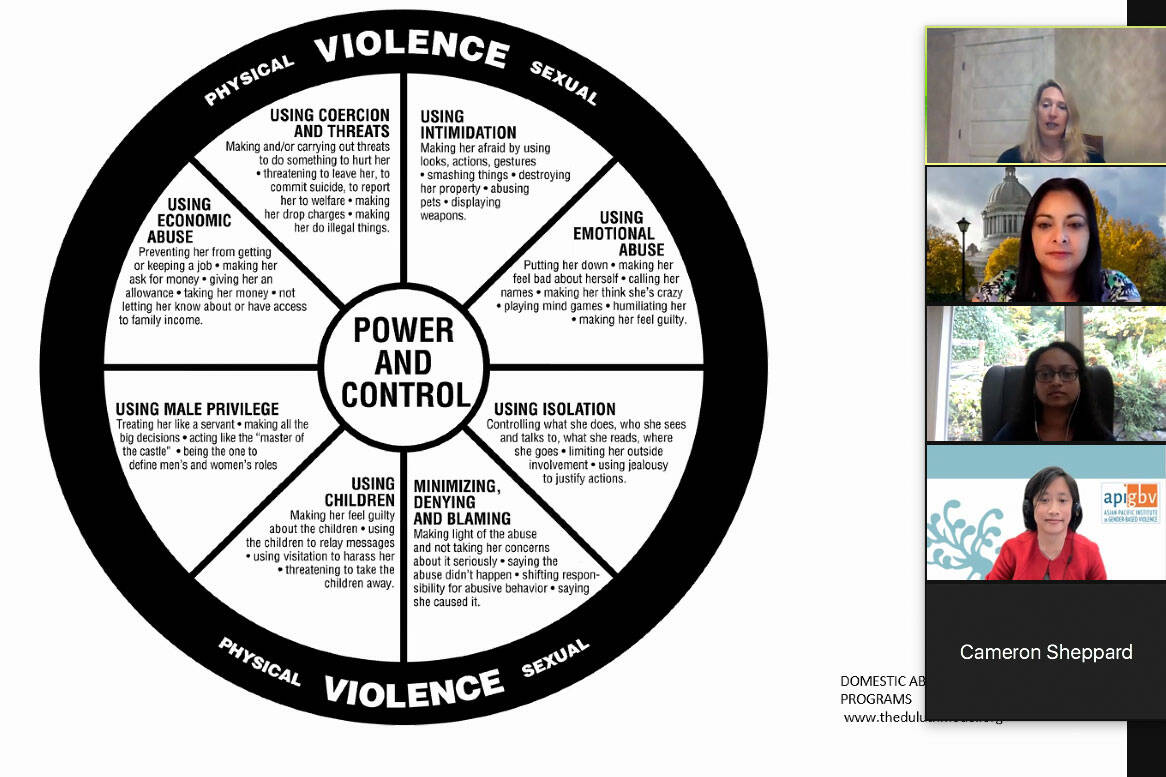

She described coercive control as a systemic pattern of behavior used to establish power over the victim. It may not directly utilize physical violence, but studies show it can be just as impactful and abusive, controlling the everyday existence of a survivor of abuse

It can include emotionally manipulative behavior as well as actions such as the withholding of documents needed to petition a protective order, using pets and children to control behavior and other threats just vague enough to not meet the legal definition of violent abuse.

The newly adopted law, which will go into effect on July 1, 2022, does not include language specific to coercive control other than outlining an assessment of how coercive control dynamics can better be addressed by the civil protection order process.

Shanahan said during her work advocating for and assisting survivors of domestic abuse, she was “haunted” by how many times victims came into her office and detailed situations and incidents in which everyone in the room knew it was domestic violence but could not get them protection or justice under the current legal definition.

“There is a gap between the language of the law and the actual experience of domestic violence,” Shanahan said. “It is critically important to integrate those behaviors into the statute.”