Most people know the Washington state folk song, “Roll On, Columbia.”

What some may not know is that the song was brought to us courtesy of the Bonneville Power Administration.

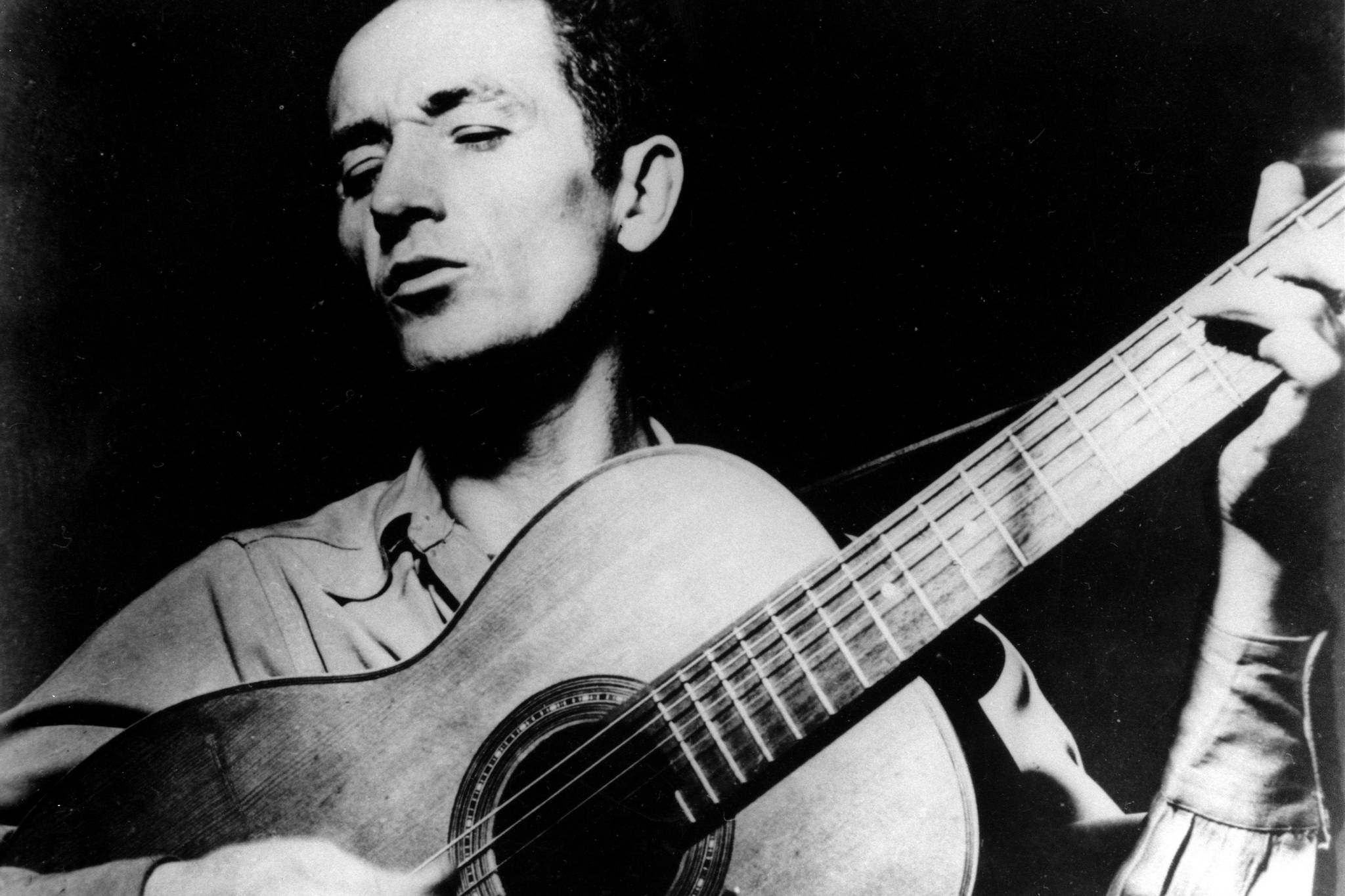

Back in 1941, the BPA hired the folk singer Woody Guthrie to spend a month driving up and down the Columbia River, looking at the dam, irrigation, and electrical transmission projects in the works there, and write songs about them. Among those songs were the classics “Roll On, Columbia,” “Pastures of Plenty,” and “Grand Coulee Dam.”

Why was a folk singer from Oklahoma cruising around the state praising these massive public works? The answer to that question may help explain why, now, the Trump administration is signaling that it wants to sell off some of those works, specifically the power grid owned and operated by the BPA (which supplies Seattle City Light 40 percent of its power). The sell-off is part of the proposed federal budget that the Trump administration released last month. That proposal states that selling off the thousands of miles of transmission lines would raise $4.9 billion for the federal government in the next decade. But really, the sale would be less about the money and more about settling a long running political score that dates back to when Woody was roaming around our parts writing songs.

Guthrie was a product of the Dust Bowl, his songs retelling first-hand experiences of living through the collapse of the Oklahoma economy and hitching his way to California. As such, Guthrie took a personal interest in projects that he felt benefited the down-trodden in the United States rather than the wealthy. What was going on in Washington and Oregon in early 1940s seemed to fit the bill.

In 1930, 10 companies owned 75 percent of the United States’ electrical supply. Leading those companies was a who’s-who of American capitalism: John D. Rockefeller Jr., J.P. Morgan Jr., Samuel Insull. Typically, favorable state governments would grant these trusts exclusive access to rivers that they’d dam to generate power—crony capitalism wrapped in a free-market guise. Private utilities also owned the transmission lines that brought that power to homes, by and large.

However, the Pacific Northwest, and Seattle in particular, had long been ahead of the curve when it came to busting this system. The citizens of Seattle got into the public-power business in 1890 when the city created the Department of Lighting and Water Works, the precursor to Seattle City Light. The city began construction of its first power-producing dam in 1902. During the Great Depression, the Roosevelt administration took this power populism to a new level. First, it built dams at Grand Coulee and Bonneville on the Columbia to generate more electricity than, frankly, anyone knew what to do with. Then, rather than sell that power wholesale to private utilities, the government transmitted and sold the power itself via the BPA. The federal government also hoped to create a massive amount of irrigation to provide reliable farmland for dispossessed Dust Bowl farmers.

This plan rubbed a lot of people the wrong way. Fiscal conservatives saw the whole thing as an expensive government boondoggle, and capitalists said it smelled of communism. So the government set out to sell the projects with plays, films, and a folk singer. In 1941, Guthrie came to Portland, where BPA is headquartered, on the recommendation of Alan Lomax, the famed ethnomusicologist. The exact terms and circumstances of his employment are weird and complicated, and are detailed in Greg Vandy and my book on Guthrie’s time in the Pacific Northwest (excerpted here). But in short, his charge was to write a song a day for a month, celebrating the dams, the irrigation, and the grid: “‘Lectric lights is mighty fine,/If you’re hooked on to the power line.” While he appreciated the money he got for the songs, by all accounts he was a true believer in the projects as well.

While several of the songs written for the BPA endure today as folk classics, they were barely used to promote the BPA, as WWII pretty much occupied everyone’s attention for the four years after Guthrie wrote them. Still, Guthrie proved to be a sort of bellweather for the BPA and its political environment. He was hired at a time of great New Deal optimism for big federal projects, but during the 1950s there was a change of tune. Republicans took power looking to rein in Roosevelt’s excesses and slashed the BPA’s budget. One BPA employee named Elmer Buehler, who had driven Guthrie around during his month with the agency, claimed he was ordered to burn all copies of a BPA film Guthrie’s music had been put to, out of spite toward the message they carried. A 1980 investigation into the claims by the BPA concluded that Buehler’s story “has remained consistent over a significant number of years and has never been refuted. It is part of the official records in the National Archives in Washington, D.C., and appears destined to become a permanent part of BPA’s history, though it may never be verified by other witnesses.”

Whether Beuhler’s account is correct, it’s no secret that conservatives have long remained deeply skeptical of the BPA and the ideals Guthrie espoused. In 1986, the Heritage Foundation published a report that argued “consumers served by the [public power administrations] stand to reap significant long-term benefits from the great efficiency and accountability that would result from placing these facilities in private hands,” while slipping in later that BPA electricity was about 70 percent cheaper than the national average. Not that price mattered. It’s an ideological argument: Selling the BPA and other such agencies would “take the federal government out of the energy generation business—where it does not belong,” Heritage contended in free market boilerplate. Ronald Reagan’s budget that year actually proposed the sale, but it was shot down in Congress.

That, too, seems to be the fate of Trump’s proposal. In a letter sent Wednesday, a bipartisan group of 22 U.S. senators blasted the idea. Among them are our own Sens. Maria Cantwell and Patty Murray, as well as several Republicans from deep inside Trump country: Both GOP Senators from Idaho, a Republican from Montana, and a Republican from Wyoming. The reason is clear: the BPA is a good deal for customers.

“Federal power marketing is one of the few federal programs that not only fully pays its way, but actually provides benefits to the Federal government balance sheet,” the senators write. “Any private entity buying PMA assets will want to recover their investment. The resulting rate increases would take money out of the pockets of consumers and businesses in our states.”

The Spokesman-Review, in an editorial published Wednesday, put it in even starker terms: “Simply put, privatizing the BPA grid would devastate the Northwest economy. And for what? Another budget proposal that isn’t grounded in reality.”

As Woody put it, in “Talking Columbia,”

Yes, them folks back east are doin’ a lot o’ talkin’,

Some of ‘em balkin’ and some of ‘em squawkin’…

Just watch this river and pretty soon

Ever’body’s goin’ to be changin’ their tune.

dperson@seattleweekly.com