Passage of Seattle’s income tax on wealthy residents was fast. Lawyers on both sides of the lawsuits challenging the law expect a ruling on its legality will be equally so.

A hearing on the tax has been scheduled for November 17, soon after which a ruling is expected, lawyers say.

“I would anticipate that the judge is probably going to spend the Thanksgiving holiday really working through this. I would expect a decision in the week following Thanksgiving,” says Matthew Davis, who represents plaintiff Mike Kunath, an investment broker.

Kimberly Mills, a spokesperson for City Attorney Pete Holmes, agrees by email that Seattle will likely have a ruling by year’s end, though she adds that appeals of that ruling will likely drag on.

Opponents of the income tax, which applies to income over $250,000 for individuals and over $500,000 for couples, have been outspoken about their strategy for defeating the tax this fall. Echoing arguments that have vexed income-tax efforts for decades in Washington, Davis says he plans to argue that cities don’t have authority from the state to levy an income tax; that state law specifically bars income taxes; and that applying the tax only to high earners is unconstitutional.

Kunath’s lawsuit will be considered beside two others filed against the tax: One brought by the Freedom Foundation on behalf of a number of wealthy Seattleites; and another brought by former Attorney General Rob McKenna on behalf of five Seattle residents. On Wednesday, a fourth lawsuit was filed by the libertarian Pacific Legal Foundation, which says, among other things, that the law violates high-earner’s due process rights.

The City Attorney’s Office is due to respond to the lawsuits in late September, and until then will be playing its cards close to its chest.

“Pete doesn’t discuss legal strategy in public; no thoughtful lawyer would,” says Mills.

In private, of course, is a different matter, and public records show that the City Council and Holmes’ office have been in regular discussion regarding the legality of an income tax since early 2015.

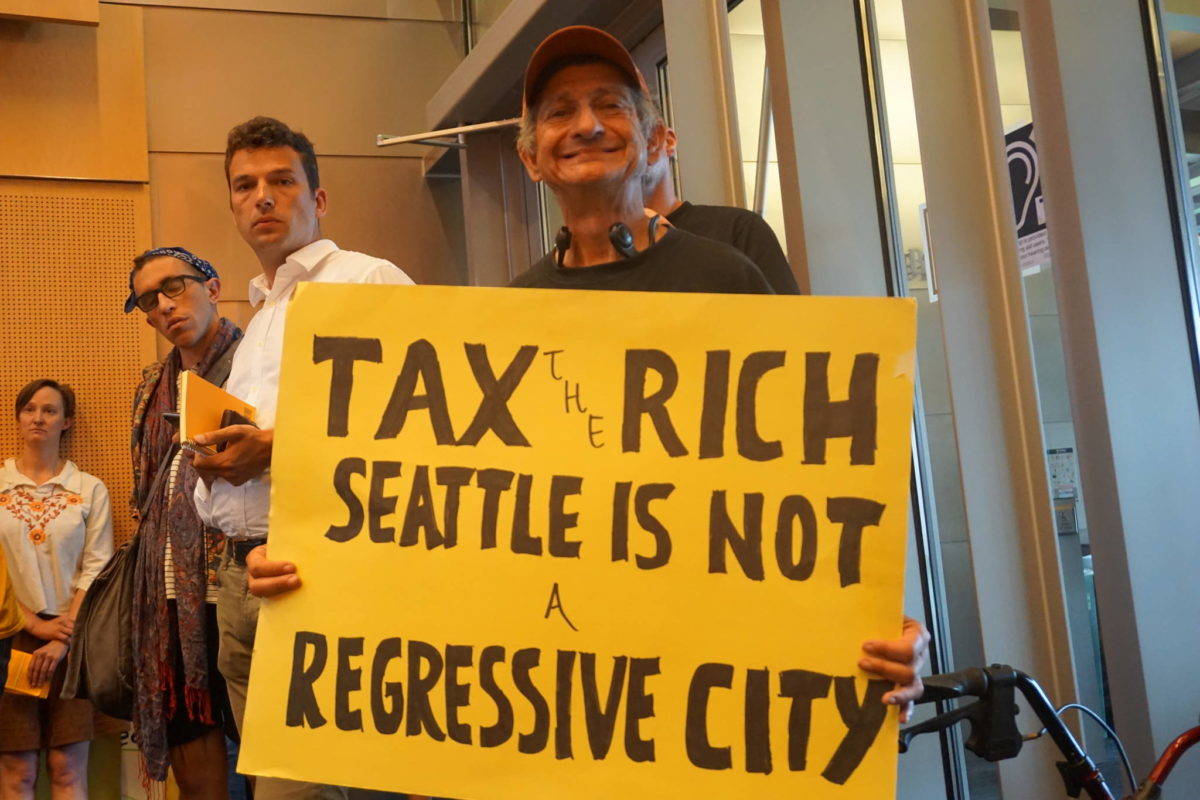

In 2014, councilmembers passed a “statement of legislative intent” asking the city attorney’s office to “investigate progressive measures like a ‘millionaire’s tax’ in Seattle”—specifically a tax on “annual individual or household earnings in excess of $1,000,000.” The statement, sponsored by Councilmember Kshama Sawant, stated that the legal memo would “prepare council and advocates of progressive revenue sources to draft legislation to institute progressive measures like a millionaires tax in 2016.”

According to emails obtained through a public records request, the city attorney’s memo was sent to councilmembers on April 9, 2015. The content of the memo is unknown, since it falls under attorney-client privilege. That said, the heavily redacted emails show that the memos were circulated widely around the council after it was prepared, and factored into conversations about creating a new tax on high-earners. For example, in early 2016, John Burbank, executive director of the non-profit Economic Opportunity Institute, wrote to Councilmember Mike O’Brien requesting a meeting to discuss “the idea of a privilege tax on the wealthy.” In response, O’Brien’s staff reached out to the City Attorney’s Office to discuss its 2015 findings. The author of the memo, Assistant City Attorney Kent Meyer, continued to share the memo throughout early 2016; in several emails he notes the memo came up in conversation, suggesting councilmembers were discussing the legality of a tax on high-earners.

The City Attorney’s Office declined to discuss the memo, citing attorney-client privilege. Several council staff members also declined to comment.

Former City Councilmember Nick Licata, who was chair of the Finance and Culture Committee when the memo was prepared, says he has only vague recollections of the memo.

“I don’t remember it being very in-depth,” he says. “I suspect that whatever we got from the law department, I doubt whether it would be pro-income-tax…”

Whatever the memo said, no income tax proposal was put forth in 2016. However, in 2017 another memo was prepared, this one by attorneys Knoll Lowney and Claire Tonry of Smith & Lowney PLLC. The memo was prepared for Burbank of the EOI; EOI in turn had a $50,000 contract to consult with the city on creating a local income tax. According to Real Change, the memo challenged the legal thinking that “municipal attorneys” have been relying on “for decades.”

The memo was prepared in March. An ordinance was introduced in June and passed in July.

In an interview, Tonry says that they weren’t addressing City of Seattle attorneys specifically when discussing “municipal attorneys” in the memo, but an argument that had “just been floating out there in the ether.”

“We brought a fresh set of eyes to it,” she says.

Specifically, the memo lays out an argument for why cities may not be as restricted in the types of taxes they can levy as previously assumed. That argument happened to get a huge boost in August when the state Supreme Court upheld the city’s gun and ammunition tax. Opponents of that tax argued that the city needed permission from the state to create the tax, also one of the arguments against the income tax; but the state Supreme Court disagreed.

“That absolutely affirms everything we said in that memo,” Tonry says.

Davis agrees that the gun and ammunition tax ruling imperils one of his arguments against the income tax. “The Supreme Court definitely is playing some games by expanding the power” of city taxation, he says. He adds, though, that the ruling only addresses one of three main arguments he plans to make against the income tax.

The city has budgeted $250,000 to hire outside lawyers to help defend the income tax. One of the plaintiffs, meanwhile, is looking for donations. Despite boasting clients that include a CEO, a senior marketing manager at Microsoft, and an investor who has “invested in over 75 companies in the Seattle area,” the group represented by McKenna has set up a nonprofit to allow people to donate to their cause.

Set up as a 501(c)(4), the tax-exempt group is required, per the IRS, to “promote social welfare.”

dperson@seattleweekly.com

Casey Jaywork contributed to this report.