At noon on Monday, April 10, at least 275 people detained inside the Northwest Detention Center (NWDC) in Tacoma refused their lunch, launching a hunger strike intended to last at least three days.

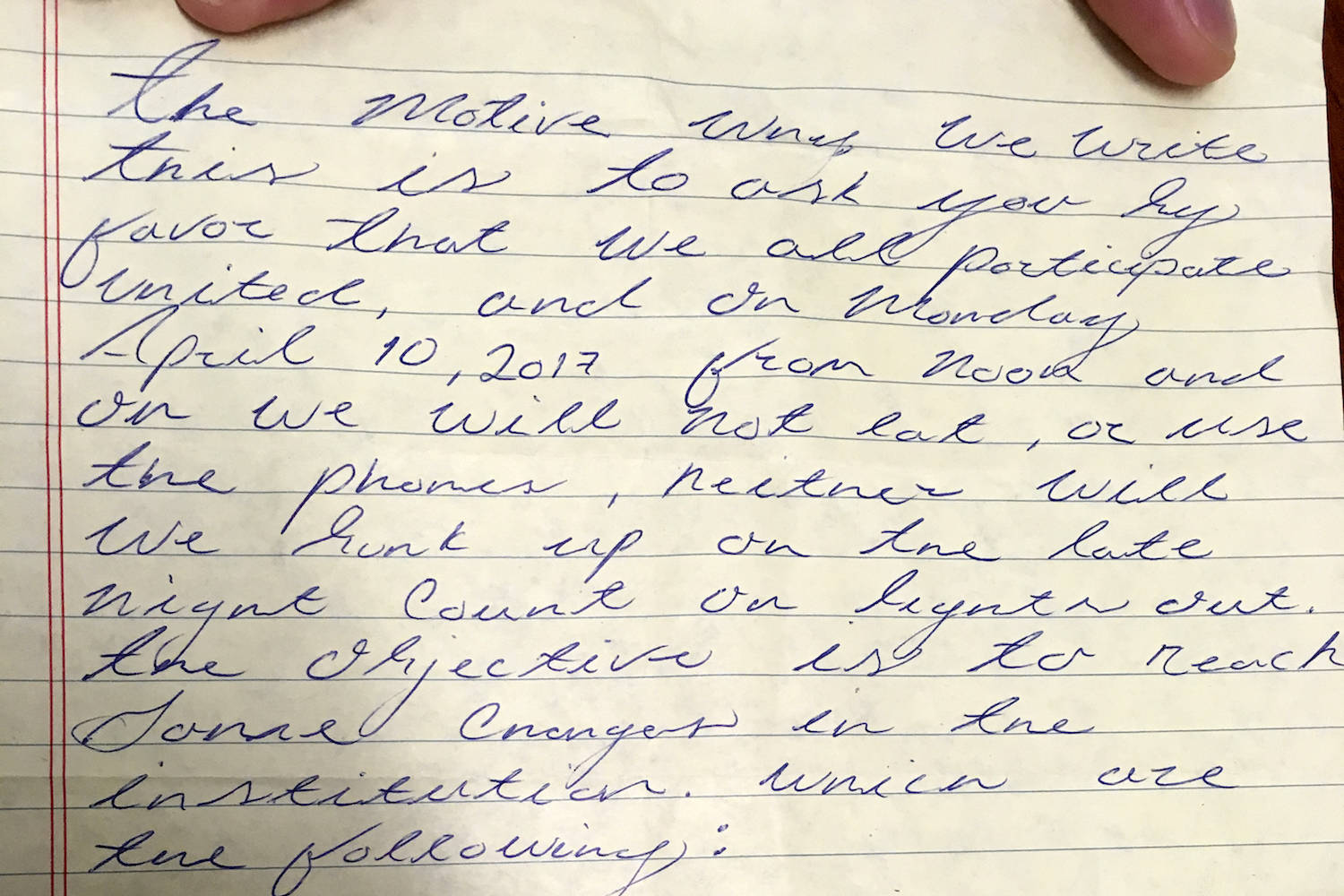

The detainees’ demands, circulated on a handwritten letter Monday, echo those made during the NWDC hunger strikes in 2014, which lasted nearly two months at a time and drew national attention. They include: Expedited immigration hearings, improvements to what’s been called “inedible” food, more reasonable commissary prices (which were already high, but recently doubled, strikers say), improved access to medical care, and an increase in the $1-per-day wage for detainee labor (which is not always paid, either, they say; sometimes they’re given a bag of chips instead).

The plan is to refuse food for at least three days because Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) “won’t recognize it as a hunger strike until they last 72 hours,” says Maru Mora Villalpando, one of the lead organizers of NWDC Resistance, a grassroots advocacy group that grew out of the 2014 hunger strikes.

As the group’s stated mission is to support the needs of those detained, volunteers rallied outside the facility Monday and plan to camp there until Wednesday. “We’re staying here the three days,” Villalpando adds, “not only because we want to know any directions from the people detained — what they want us to do — but we also want to witness if there’s any type of movement of GEO or ICE to retaliate.” (GEO Group, one of the largest private-prison companies in the nation, operates the NWDC.)

In 2014, detention center officials put hunger strikers in solitary confinement as punishment. Villalpando says if they do so again, “The first thing we do is we make it public.” Activists also have a legal team assembled to protect detainees’ rights to peaceful protest, should they need to. In 2014, after legal pressure from the ACLU and Columbia Legal Services, hunger strikers were released from solitary.

Villalpando hopes that the fact that the activists are outside watching will give GEO and ICE officers pause, though she is less convinced that appealing to the current federal administration will yield all that much. She says she recently returned from an Inter-American Commission on Human Rights hearing in Washington, D.C., and for the first time in two decades of such meetings, the United States did not show up.

“For us, it was just another sign that we’re dealing with a fascist regime that doesn’t care about human rights,” she says. But that’s why she believes this kind of civil disobedience is so important. “At the end of the day, public opinion will make changes here.”

From time to time, a striker will call Villalpando and give her the update. She often puts the detainee on speaker phone so that he or she can hear the activists cheering outside, to show him or her that people care. “We’ll be here,” she says, “we’ll be here, whatever it is they decide.”

sbernard@seattleweekly.com