Last week, I feared Mayor Greg Nickels would find a way to avoid killing the Seattle Monorail Project (SMP), so I was pleasantly surprised when he yanked the city’s support on Friday, Sept. 16, and forced another vote in November. Nickels didn’t kill the project, but he put a pillow over its face. With any luck, the voters will finish the job.

For once, we’re seeing some of the virtues of the “strongman” governance Nickels brought to City Hall. Strongmen are useful when they go to bat for the right causes—when they help the little guy or stand up for common sense, safety, and prudence. So many of Nickels’ activities to date have benefited other Goliaths, like Paul Allen and downtown developers or Sound Transit. Or they have been for the sake of continuing to consolidate power by intimidating city employees and the City Council into toeing the mayor’s line. This time, we needed a strongman to break the spell that seems to hold the monorailers in thrall.

But Nickels‘ monorail action raises issues about local governance that go beyond one bungled project. While the mayor has consolidated enough power to muscle his way toward re-election virtually unopposed, he is not in a position to kill the monorail outright. That’s because as a city and a region we have outsourced government to so many public and quasi-public entities that even a strongman is often left chasing chickens in the barnyard.

While Seattle can stymie the monorail, it cannot disband SMP, pay its debts, sell off property, stop collecting taxes, and send the staff off for cult deprogramming. The voters created it, and only the Legislature or SMP itself can put it down. Nickels couldn’t give it the coup de grâce because he doesn’t have the power.

SMP is just one of many entities the city has limited control over. Stadium authorities, the Port of Seattle, various transit agencies, and the Seattle School District are some others. The mayor and City Council do not run the buses, light rail, or monorail; they have limited say in how schools are run; they don’t control the airport or the waterfront, and they are periodically held hostage by billionaire sports franchise owners who have demanded tailor-made mini-governments to cater to their whims.

This is not by accident, but by design. Since the 1980s, U.S. cities have virtually reinvented and rewired local governance through the creation of an endless array of so-called “special-purpose” authorities. For an excellent overview of the phenomenon, see the June 2003 paper by University of Illinois–Chicago political science professor Dennis R. Judd, Reconstructing Regional Politics: Special Purpose Authorities and Municipal Governments, published by the Great Cities Institute (www.uic.edu/cuppa/gci).

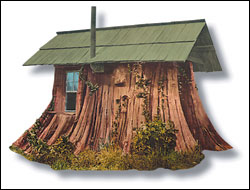

Another term for them is “designer” governments. They have a limited purpose—or start out that way—but also limited accountability. They tend to be governed by weak boards of people representing constituencies with vested interests in the work of these entities. They often focus on specialized projects and are run by professional staffs who work hard to fend off know-nothing meddlers (once known as citizens). The lawyers and lobbyists who design them often find ways to circumvent the daylight of disclosure or oversight. These public and semi-public entities are often born of an alliance between government and big business, and they seek to do their jobs without the inconvenience of broader accountability. In other words, it’s fox-enter-hen-house time.

Thus we end up with entities like the Port of Seattle, with an enormous budget and vast taxing authority—yet few in the city understand what it does, where the money goes, and who it benefits. An entity that once was about managing shipping terminals and airports has experienced mission creep. These days, it’s involved in condos, tourism, and development. Occasionally, the voters elect reformers to the Port—and to the School Board—but they are soon like bugs caught on flypaper. Without staff to assist, without a budget, without real resources, their reform agendas stall. Eventually, the Patty Hearst syndrome kicks in and the reformers morph into enablers. We pay them next to nothing to oversee people with more expertise and big salaries. In short, the public is represented by amateurs while designer governments have all the time, money, and pros on their side.

The result is that these boards often don’t do their jobs. The monorail board is a particularly egregious example of a designer government run by boosters whose oversight has been lacking, its performance negligent. As an all-too-common example of its shameful behavior, the SMP responded to State Auditor Brian Sonntag’s critical report of the agency last week by announcing they’d been given a “clean” bill of health, despite the audit’s discovery of inaccurate board minutes, violations of state open-government laws, illegal consulting contracts, and an absurd financial structure.

Current state law does not allow more comprehensive audits of designer governments, but Sonntag says Initiative 900, the performance-audit initiative on the November ballot, would change that. Passing I-900 would give citizens and public officials a means to find out what’s really going on. Perhaps it would enable citizens to put a stop to runaway projects.

Then we could clean up our messes without resorting to a strongman to do it for us.