Following the April release of an audit that showed that homeless riders are disproportionately cited for fare evasion on King County Metro’s RapidRide bus lines, County Executive Dow Constantine wants to soften the transit agency’s fare enforcement policies.

The King County Auditor’s Office report found that homeless riders accounted for 25 percent of all financial penalty citations for and 30 percent of all misdemeanor charges for fare evasion. The report also found that while 19,000 individuals were penalized for fare evasion between 2015 and 2017, 99 individuals (the majority of whom were either people of color or homeless or both) accounted for 6 percent of all penalties. Additionally, less than 3 percent of fare evasion fines were paid in 2016, leading them to be referred to the county collections program.

As the fare enforcement policies are currently written, riders found without proof of payment on RapidRide buses are first given a verbal warning, then a civil infraction and a $124 fine. Subsequent infractions could also warrant a misdemeanor charge.

After the audit was released, King County Metro suspended referrals of potential misdemeanor charges for fare evasion to the Metro Transit Police (previously, these officers would then submit chronic fare evasion to the cases the Prosecutor’s Office for prosecution). The agency also announced that it would convene a stakeholder group to devise solutions to the issue.

On July 26, Constantine transmitted legislation to the King County Council that would bar civil infractions for fare evasion from being referred to the county justice system. Additionally, the proposed policy would reduce fines from $124 to $50 or less (the exact figure hasn’t been identified yet), and allow for fines paid within 30 days of issuance to be reduced by half. Riders could also resolve fare violations through non-monetary options, such as community service with (yet to be identified) local non-profits or enrolling in the ORCA LIFT reduced-fare program. (While some transit advocates have argued for abolishing fares altogether, ride payment accounts for roughly one-third of Metro’s operating costs.)

“What we’re going to do now is take all of those infractions out of district court and handle them administratively within Metro—basically remove the direct connection from the fare evasion tickets [to] the court system,” Metro spokesperson Scott Gutierrez told Seattle Weekly.

While Metro’s decision from April to suspend referrals of misdemeanor fare evasion cases to the Prosecutor’s Office isn’t written into the new legislation, Gutierrez said that it isn’t going anywhere. “That’s permanent. That’s something that we’ve adopted.”

Under the new policies, riders who do not address infractions within 90 days of receiving them will be placed on a “pending suspension list” from Rapid Ride buses. If fare enforcement officers encounter them on transit without proof of payment afer this period, they will be issued a suspension for 30 days.

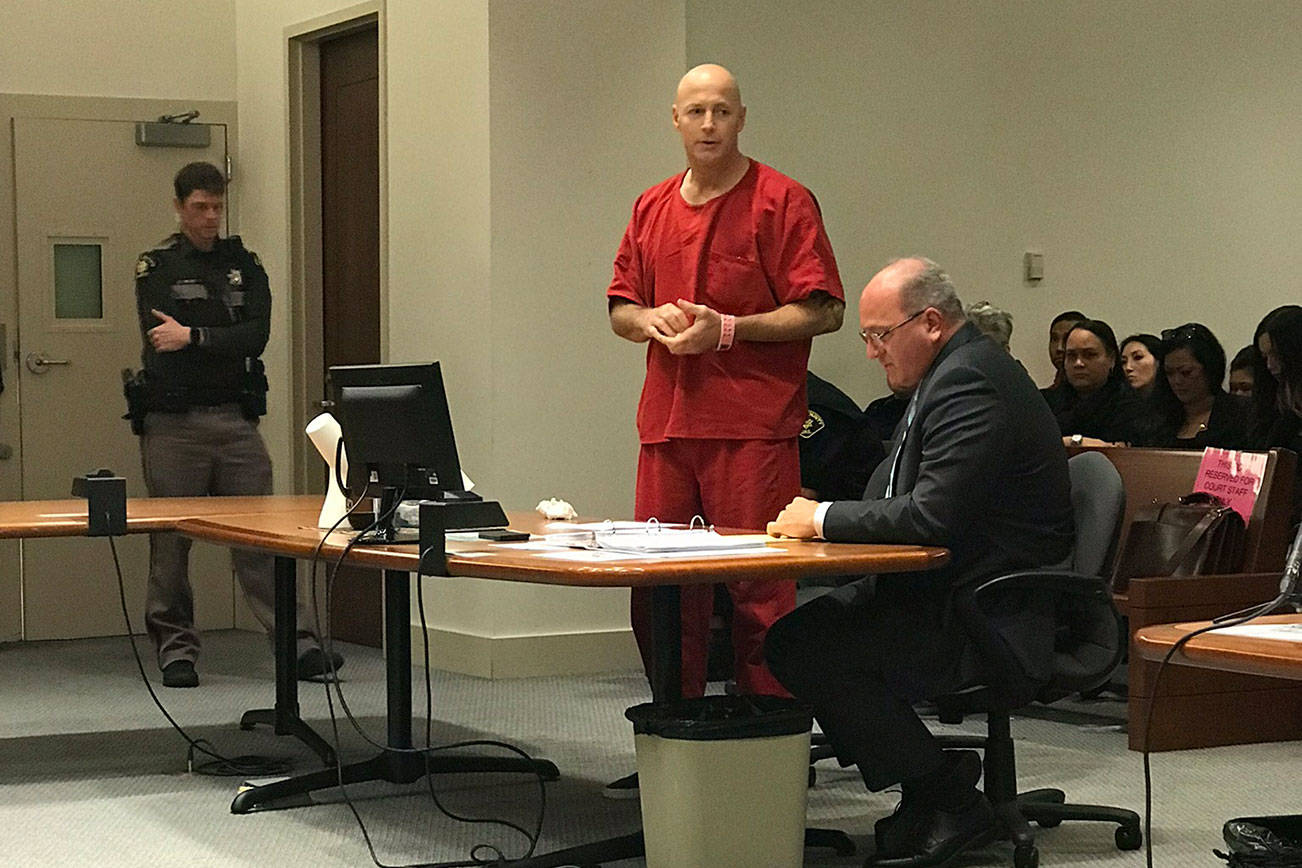

Mark Norton, King County’s superintendent of transit security, said that while riders who continue to violate temporary suspensions of Rapid Ride transit use without proof of payment could face trespass charges, but that the new policies will keep most riders from becoming chronic fare evaders. “What we’re really counting on is that we’ve built in enough off ramps and enough outreach that we’ll end up in this situation really rarely,” he said in reference to filing trespass charges.

Homeless and equitable transit advocates who were involved in stakeholder discussions with the county (which will continue to help shape future policy) praised the proposed policy changes in a July 26 press release.

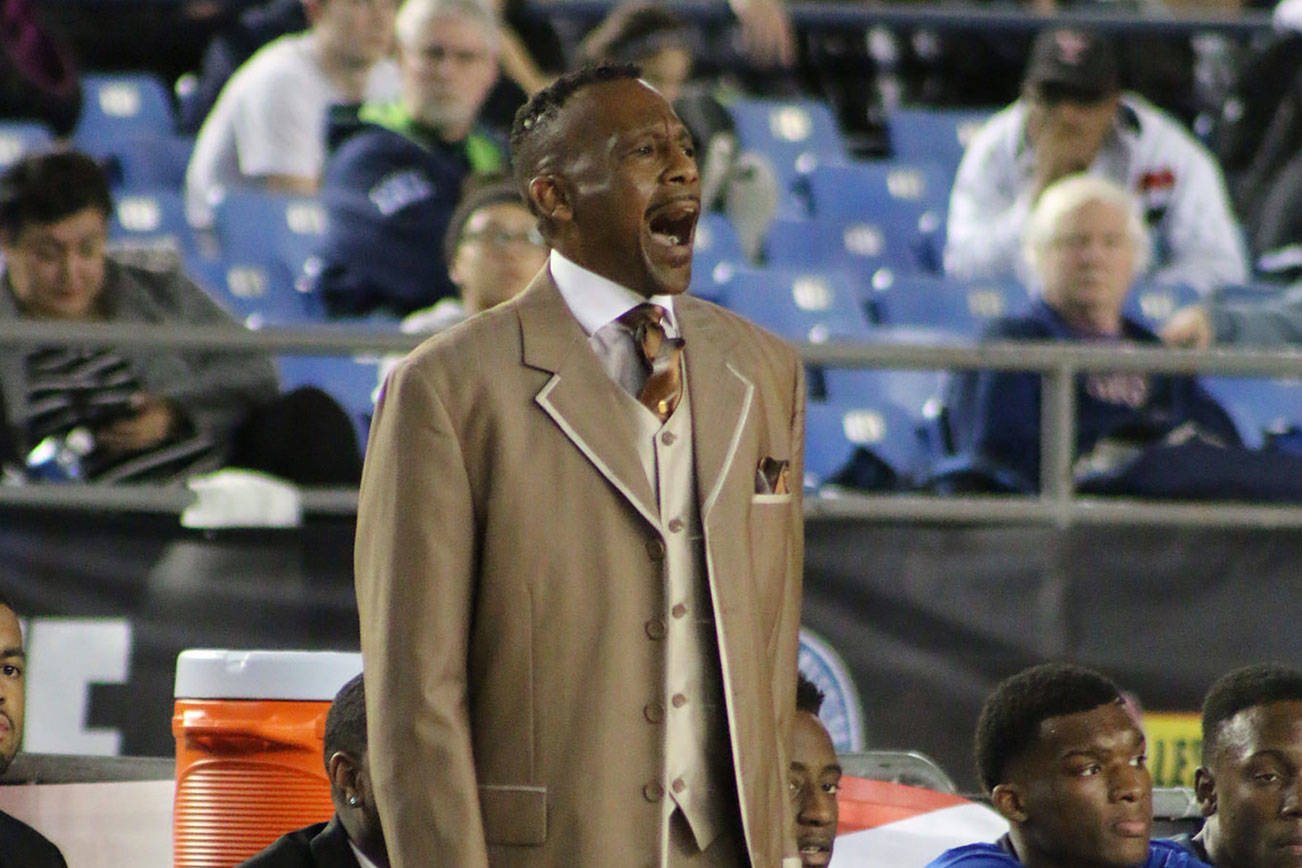

“We appreciate Metro’s willingness to work with the community to move beyond a fare enforcement system that punishes low-income people, homeless people, and people of color,” said Katie Wilson, general secretary of the Transit Riders Union. “Not being able to pay a fare should never be an entry point to the criminal justice system, or lead to calls from a debt collector for a ticket you can’t afford to pay. We can do so much better, and this legislation opens the door for that work to happen.”

Correction (July 30): After the publication of this story, King County Metro contacted Seattle Weekly to clarify that riders who don’t address infractions within 90 days will be placed on a potential suspension list and then issued a subsequent 30 day suspension if their infraction continues to go unaddressed.

jkelety@seattleweekly.com