The Indian’s night promises to be dark.

—Chief Seattle

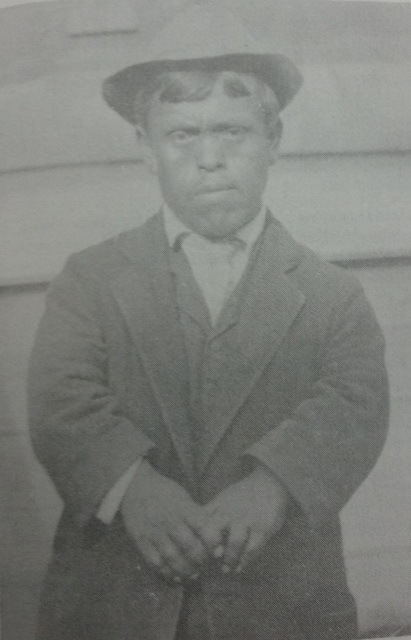

Moses Seattle was not like his famous grandfather in many ways. Chief Seattle was over six feet tall, and went by the nickname the “Big One” among French fur traders. Moses was a dwarf. The two never met, since Moses was not born until six years after his grandfather’s death in 1866. It was only six years, but in a lot of ways Moses’ world was more like the world we live in than the one his grandfather lived in. Moses was Chief Seattle’s first descendant born on a reservation, and he would be Chief Seattle’s last descendant ever born to two Native parents.

His life was hard, and ended sadly, but there has never been another person from our region remotely like him, for his short life connects the ancient mythology of the Puget Sound area to our modern era.

Moses’ existence is first confirmed in the white historical record when he started attending a Catholic school at age 10. The school was located on the Tulalip reservation, where a lot of the Duwamish side of his family lived. He was written up in the school magazine, The Youth’s Companion, under the tasteful headline “OUR LITTLE INDIAN DWARF.” His teacher wrote that he had the face and coarse voice of a full-grown man. She also mentioned that it was hard to tell what he was saying as he did not speak much English yet.

Even more than by his height, all the faculty were stunned by his incredible strength, and he was nicknamed “little Samson” after the Old Testament strongman. Being incredibly short, Moses worked out a lot to compensate, and eventually bulked up to 200 pounds of muscle. Shortly after Moses graduated from the school, a reporter visiting the Suquamish reservation on Kitsap Peninsula—where Moses was born—condescendingly noted that he was very bright, spoke perfect English, “and is the pet of all the Indians on the reservation.”

These early white accounts, though, do not touch on the substantial mythology surrounding Moses Seattle. According to his own people, Moses Seattle was born a gelatinous pile of flesh and hair without any bones.

An early anthropologist tantalizingly mentions a mysterious ritual, involving blood on a war club, used to help Moses grow a skeleton. This was not elaborated on until the 1930s when a University of Washington anthropologist, William Elmendorf, spoke with the Allen brothers, two Twana elders from Moses Seattle’s generation. The brothers told him that Moses’ mother, who was married to Chief Seattle’s last surviving son, Jim Seattle, was unable to get pregnant. At the time she was trying to conceive, a Duwamish doctor came back from a place called the Ghost Land with a spirit he’d kidnapped.

“They brought back a really dead person, one who belonged down there,” the Allen brothers said. The people on the reservation told the doctor, “Give that dead stolen soul to some woman here, so she can have children.” The doctor picked Moses’ mother.

Even in that time and culture, this was all considered strange, but not unheard-of. Belief in reincarnation was common among Puget Sound natives, but usually the ghost came into the woman’s body naturally, “like a spark of fire,” the Allen brothers told the UW researcher. The ghosts used in reincarnation usually came from a place located beyond Ghost Land. In Native languages, this place is literally called Go Further—home to ghosts so old and frail that they lose all memory of who they are and are ready to take on a new body to start the process of life all over again. According to the Allen brothers, the ghost used for Moses Seattle was not quite dead enough yet, which might have contributed to his health problems. This story, along with being the grandson of a famous chief, helps explain why Moses was so popular on the reservation.

Despite being well-liked, there is no way Moses could have become Chief of the Suquamish. His own father, Jim Seattle, had lost the family’s right to the Chieftainship due to his violent temper. Like his father, Moses was also remembered for the occasional violent outburst, but because he was so short it was generally regarded as a joke. According to his friend Ernest Riddell, whose memories of Moses were published in the book Kitsap County History, the thing Moses was made fun of for the most was playing baseball on children’s teams into his 20s. When people teased him for this, he would run at them in a violent rage. Those chased by him all remembered that he could bolt fast despite his malformed and crooked legs.

Not only was Chief not a job option for Moses, there weren’t many job options at all for a Native at the time. For a while, Indians weren’t even allowed to live in the city named after Chief Seattle.

The late 1800s are known among white people as the time of Sherlock Holmes, Dracula, steam-powered contraptions, and corsets, but in Puget Sound tribal history, that time is known as the White Man’s Speluch. The word “speluch” comes from Twana, a Puget Sound language, and literally means capsizing. Besides the White Man’s Speluch, the only other speluch in Native history was the time in the primordial past when the Changer separated animals from people, shrunk insects to make them less dangerous, and sucked the life out of rocks to stop them from moving around. The speluch that Moses Seattle lived in was no less extraordinary—a time when the children of former slaves and former chiefs worked side by side in the hop fields, and entire tribes that had been around for 10,000 years were going extinct from the new diseases. It was against this backdrop that Moses would have to find work. It was also against this backdrop that he would become an alcoholic.

Like most Indians from this time, Moses wound up working a lot of odd jobs, like picking hops or, in the off-season, performing in a circus freak show under the name “The Wild Man From the Spanish Flats.” Moses was known to eat mud during his freak-show performance, a feat people would pay a nickel to watch. According to his friend Riddell, the mud was mixed with chocolate to give it a better taste, though this sounds like a small consolation. When he wasn’t working in the hop fields or eating mud for people’s amusement, Moses’ main source of income was ferrying people around Puget Sound in his dugout canoe.

It was in this role that Moses finally gained people’s respect. Incredibly strong, he became locally famous for being the fastest ferryman on Puget Sound. Not only was he adept with a canoe, he was also an outstanding swimmer. Those who knew him said he could exploit the physical properties of his square body to float on top of the water like a balloon. According to Riddell, one night when the waves were too rough, his boat sank and his passenger drowned, but Moses drifted on the freezing water for almost a mile before he floated into some Indian fishing nets and was rescued. Another time, when a drunken passenger attacked him, the boat sank, but Moses swam to shore carrying the passenger’s sister with him, saving her life. The passenger who attacked him drowned, Riddell said.

When he wasn’t working, Moses’ two loves were baseball and music. He taught himself how to play the accordion by ear. In addition to Native music, Moses was an expert at playing square dances, polkas, and waltzes at parties thrown by loggers and Indians. Those who remembered these dances said he would rest the large accordion on top of his legs so it didn’t get too heavy as he got drunk. The drunker he got, the better and wilder his performances became.

It was shortly after one of these parties that Moses was killed. He and his friends met up with some sailors, stationed at the nearby naval base at Bremerton, who could buy them whiskey (under the racist laws of the time it was illegal to sell liquor to Indians), and the whole group went out into the woods to have a party and get drunk. After Moses finished playing a few songs, they started passing around the bottles. At the murder trial, the sailors testified that as the whiskey supply started to run low, the group switched to a combination of beer and whiskey to keep the party going.

What exactly happened next is vague, since nobody wanted to talk about it later. Moses and his best friend, Bob Purcell, whom he’d been living with for months, started arguing. What they were arguing about is unknown, but it was probably something trivial, since the sailors also testified that everybody at the party was so drunk that none of them were in possession of their senses. Soon Moses and Bob started physically fighting each other. Bob grabbed Moses and shoved him into the fire. According to hearsay, Moses got out the first time and started rolling around on the ground while the drunken crowd laughed, but then Bob grabbed him again, and this time not only shoved him into the fire but held him down in it until his flesh was burned all the way to the bone, according to newspaper accounts of the crime.

The sailors had already broken the law by buying the whiskey, and a lot of the other guests probably had criminal records, so the last thing any of them wanted was to be found at the scene of a murder. Within minutes, all the partygoers fled. Moses’ badly burnt body was left in the cabin by the dying fire.

But Moses wasn’t dead.

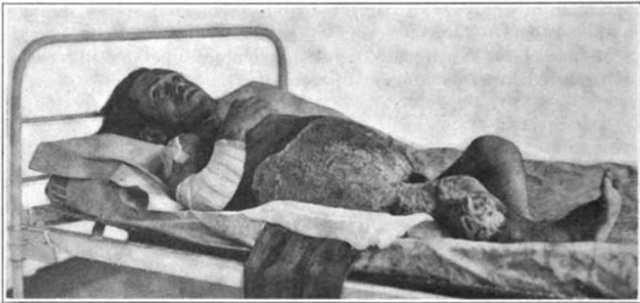

From the very little documentation left about Moses Seattle, one thing is clear: He was tough. For two days he lay inside the abandoned shack next to the extinguished fire. His body was covered in third-degree burns, and he was unable to move. There was still liquor around the cabin, and even in his critical, immobile condition he continued to drink until somebody found him. He was taken to the nearby naval hospital, where the doctor noted in a subsequent journal article that Moses was still clearly under the influence of alcohol. In his rolled-up coat, which he’d propped under his head as a pillow, there was a three-quarters-empty pint flask, which the doctor confiscated.

Only one photograph of Chief Seattle was ever taken, and even in that photograph he is clearly uncomfortable, with his eyes closed the entire time. He didn’t like cameras; they weren’t part of his culture. Moses Seattle grew up with cameras, and in his deathbed photo he is indifferent to them. He is looking off into space, clearly aware that he is about to die, and does not seem to have any opinions one way or the other on being photographed.

Moses was born under the supernatural treatment of the same kind of doctors his people had been using for thousands of years, yet only 30 years later, his death was being overseen by a military doctor at a naval base. For his birth all we have are legends recorded over 50 years later, but for his death we have graphs that show his temperature, respiration, and pulse up to the moment of death. From the autopsy we know that his spleen was half the normal size, that his liver and kidneys were enlarged from alcoholism, and that his heart was overworked.

Moses died of shock from the burns a couple of days after being admitted to the naval hospital. In the newspaper coverage of his murder trial, the reporters get a lot of things wrong. They say he was Chief Seattle’s son, when he was his grandson; they say he was the last of the Seattle family, when Chief Seattle actually had several biracial great-granddaughters still living; and they say Moses was a Chief when he was really just a nobody. One thing the newspapers got right is that none of the Indians would testify.

Officially, those who admitted to being there the night Moses was burned alive said they were too drunk to remember anything, and would not work with the white authorities. The only person to come forward and officially say he saw Bob Purcell holding Moses down into the fire was a man named John Smith, whom, the papers contemptuously noted, was a “half-breed.” Since at the time “half-breeds” were regarded as untrustworthy, Bob Purcell walked and never appears in the historical record again.

On his deathbed, Moses didn’t say what happened either. Officially he wasn’t sure, and guessed he must have rolled into the fire in his sleep. He was still loyal to his friends, even if they murdered and abandoned him. However, after the trial, Moses’ murder became well-known. It was part of his lore.

At first Moses was buried in the naval base’s graveyard, but his body was soon exhumed by his people and brought back to the reservation to be buried alongside the rest of his family. The Suquamish graveyard is now most famous for being the resting place of Chief Seattle, but surrounding Chief Seattle’s grave are many gravestones merely marked “Unknown.” To this day somebody leaves flowers and clam shells on these unknown graves. Seashells are scattered all over the cemetery by the modern Suquamish as a way of finding common ground with their ancestors, who spoke a different language and lived a very different way of life.

I went to the graveyard looking for Moses Seattle’s grave, but couldn’t find it. It is possible that his is one of the graves marked with an Unknown, or it could be one of the markers that is just a pile of rocks now. Either would be fitting since Moses was totally forgotten within a couple of decades after his death. A white friend of his, who knew of the supernatural circumstances surrounding his birth, summed up his life and adventures in the Kitsap County History as follows: “Fate, which had led the little dwarf into a modern world from out of the dim mists of an ancient belief, mercifully allowed him to slip back into the mysterious land of the dead.”

There is no death, only a change of worlds.

—Chief Seattle

The streets of Ghost Land are a lonely place. Not even the ghosts who live down there like it that much. They frequently come to the land of the living to kidnap our souls, and bring us down there to keep them company, and make them happy. There are records of some living people going down there just to look at the scenery, but for the most part the only people who went to Ghost Land were doctors who went down there to recapture their patients’ stolen souls before the physical body died of illness or insanity. The trip was dangerous and involved passing Bad Water Creek, a creek filled with millions of worms which instantly rotted anything that touched them, from a finger, to a foot, to an entire body. Some of the things the ghosts do are strange, they sleep when its light out and do a lot of other things the opposite of the way the living do, but their world is mostly like our world, except inhabited by ghosts. One of the last doctors who was still making trips to the Ghost Land into the 1930s even remarked that they have stores and automobiles down there now, just like up here.

In the ghost village Moses Seattle would have been reunited with his family, since by this point almost all of them were dead. He would have met famous relatives like his aunt, Princess Angeline, who is supposed to haunt the Pike Place Market, and he would have met obscure relatives like his cousin Lizzie. His cousin Lizzie was another grandchild of Chief Seattle who’s life didn’t turn out well. She married a white man so abusive that she craved a daughter to keep her company. When she gave birth to a boy she hanged herself, unable to stand the thought of having brought another man into the world. Her mother, Princess Angeline, was the one who found her body hanging from the ceiling, with the baby wrapped in a basket beneath her. Princess Angeline cut down her daughter’s body and raised the baby herself. The most intimidating relative for Moses to meet would have been his grandfather, Chief Seattle. This would be the first time the two of them ever saw each other. They would have a long time to talk while awaiting their reincarnation, it would be interesting to know what they thought of each other. Chief Seattle was everything Moses was not; he was tall where Moses was short, he was respected where Moses was a joke, and he was famous where Moses was obscure.

In many ways, Chief Seattle and Moses are both products of their era.

Chief Seattle lived during the last age of Famous Indians, and Moses Seattle lived in the beginning of the age of Unknown Indians. In the early 20th century, Sears catalogs used to sell “Vanishing Race Slideshows”: a collection of pictures of Indian chiefs like Chief Seattle and Chief Joseph. These were advertised with the message that the American Indian was soon going to be extinct, but by sending in a little cash you could get your very own set of commemorative slides to show your grandkids what an Indian was. Despite the predictions of the white population of the United States, the Native population did not actually vanish. But they did stop being famous.

There is a party game I like to play in which I get a group together and try to come up with 10 famous Indians born after the year 1900. They can be famous in any category, and they can be born anytime in the last 100-plus years. Once I played with a friend of mine who had previously beaten me in a contest to name the most kinds of cheeses; his incredibly well-read girlfriend, who works at University Book Store; and a girl who took some classes on American Indian history. Among the four of us, we came up with five: Sherman Alexie, Gary Farmer (the heavy-set guy from Smoke Signals and Deadman), Sacheen Littlefeather, and two people I’d never heard of before and haven’t since. We later expanded the game to include Native Mexicans, South Americans, Polynesians, Maoris, Aborigines, or anybody else descended from the original people of the New World and were born in the 20th century or later. We still could not get more than five. When we couldn’t, the girl who worked at the bookstore got really angry: “What in the fuck does that say about us?!”

David Lewis is from Seattle, where he graduated from American Indian Heritage High School.

Seattle Weekly delivers the latest in city politics, crime, and business news. If you know something we should know, e-mail news@seattleweekly.com. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram or subscribe to our weekly newsletter for more Seattle news.