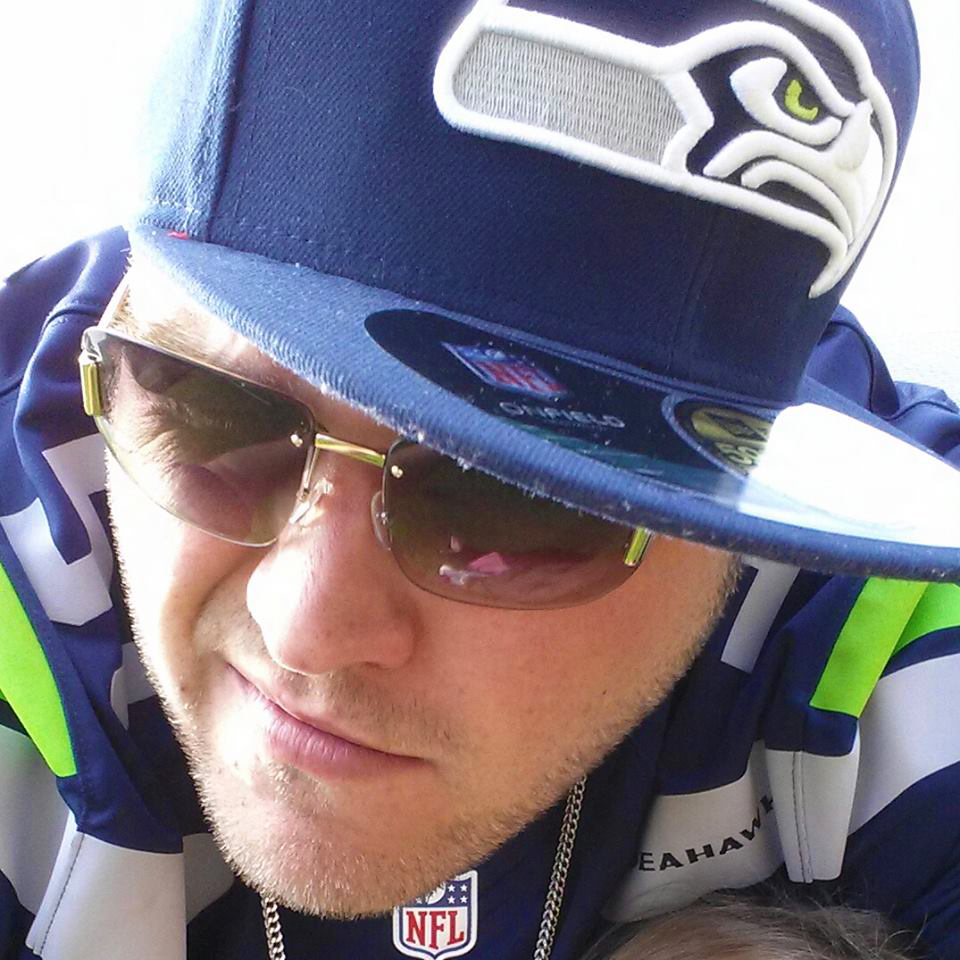

Chase Houston made Seattle history as the first fan to catch a home run ball hit into the Safeco Field stands. A committed Seattle sports fan, he was also a 12th Man to the core—“He wore Seahawks gear down to his socks,” said a friend. “It wounded him when they lost.”

Not literally, of course. Police bullets did that, mortally. Two months ago, a life of mostly fun and games ended in gunfire at Houston’s storage locker in Spanaway. Police were called after the 30-year-old father of two began Biblically ranting on his Facebook page. He announced that God was talking to him. And that he was Jesus Christ. “God just recorded a rap song with me,” he said in one of a series of rambling posts from his laptop. “We are going to change the world.”

Jobless and camping out in the storage unit, Houston was typically a 300-pound gentle giant, family and friends would later say at his memorial service. “He was a big charmer,” friend Krista Myers told mourners wearing Seahawks garb in Houston’s honor.

But he’d begun to scare people, including his wife. The couple had split a few weeks earlier, and he was calling and threatening her. He told her she was “the devil and [she] will burn in hell and God wants my daughter,” she said. He was also smoking meth.

On December 3, his wife sought a restraining order. He’s a gun collector, and, she noted in court papers, “is not stable at this moment.” By late that afternoon, after a Pierce County Sheriff’s SWAT unit arrived at Garage Plus Storage on Mountain Highway East, the protective order was moot. Her husband was dead.

Television and news reports called it a standoff. They said Houston fired first and might have taken his own life. Sheriff’s spokesperson Ed Troyer tells me, “Remember, he shot first hitting one of our deputies in the chest. Thanks to his vest, he survived.” Houston had been smoking meth for two days, said Troyer, and had threatened to kill his wife—“and told us he would do it. At that point we needed to confront him.”

Troyer couldn’t provide other details; a final report on the shooting is still being prepared, he says. (That’s also the case with the fatal shooting of another suspect by a deputy in Spanaway a week ago. While being arrested on a warrant, Michael Bourquin, 21, reportedly used pepper spray on deputies and was shot four times, according to news accounts.)

Chase Houston’s father thinks he can fill in some of the blanks about his son’s death, however—a version different from the sheriff’s. “They fired first, not Chase,” says Randy Houston, who was at the scene when Chase died and has talked with a detective handling the case. “The detective told me the SWAT team shot him in the stomach with a rubber bullet. He had been standing there talking to them at his door.”

Though stunned, Chase ran up a stairway to his loft (the carpeted two-level unit held Chase’s small studio where he recorded rap songs). He returned with a handgun and began shooting, Randy says he was told. When the smoke cleared and the team entered, Chase was dead from police bullets.

“They have security video of him,” Randy says. “The detective said one of the bullets hit him in the neck. He said he suffered for a while. They said I wouldn’t want to watch the video.”

The father says a toxicology report he obtained shows a high level of meth in Chase’s system, along with marijuana and traces of oxycodone. “He’d lost his wife and kids, was on drugs, was angry. He wasn’t himself in any sense,” Randy says. “He had no record, he was a good kid.”

Randy understands that Facebook friends were concerned about Chase’s welfare, and urged caution: If police or anyone tried to touch him, Chase had posted, “I will rip out your throat.”

“But they checked on him the day before and all was OK,” says Randy. “They came back the next day and then they called in SWAT. They knew they were dealing with an unstable person. I think they overreacted. Someone in that state, you shoot him with a ‘less-lethal’ bullet, as they call it, and you don’t know what’ll happen. I asked to talk to him and they wouldn’t let me.”

Randy says he can’t get his head around the senselessness of it all. “I just wonder what he was thinking when they shot him. Did he realize why they were there, who they were?”

At a memorial service in Bonney Lake a day before the Seahawks played the 49ers in the playoffs last month, fellow 12th Man fans filled the pews of New Hope Community Church. “He was a big, lovable guy, he grew up with my son,” remembered Renee Olson, a best friend of Chase’s mother, who died from cancer when he was young. A video of Chase’s life flickered past—childhood days, playing sports at Puyallup’s Emerald Ridge High, on vacation with his wife and children. It was a movie with a sad ending. Still, said a friend, “A man’s faults can’t sum up his life.”

randerson@seattleweekly.com

Journalist and author Rick Anderson writes about crime, money, and politics, which tend to be the same thing.