Carl LeCompte’s Oreo milkshake comes with little cookies surrounding the straw. It’s a shake befitting someone young, innocent, and appreciative of sensory pleasures. “My little indulgence,” he calls it after collecting the concoction and an Italian sandwich at a Redmond Potbelly.

The 29-year-old Microsoft programmer, a member of the team responsible for Internet Explorer, also likes walking on the beach, hiking in the woods, and feeling the wind on his face and the rain in the air. He also enjoys a fairly active social life. Today, a Thursday in late February, he’s carrying dice in his backpack that he will later take to a weekly session of Dungeons and Dragons. On Fridays he meets another set of friends to play board games like Settlers of Catan. Tuesday nights he devotes to group screenings of the Star Trek series Deep Space Nine.

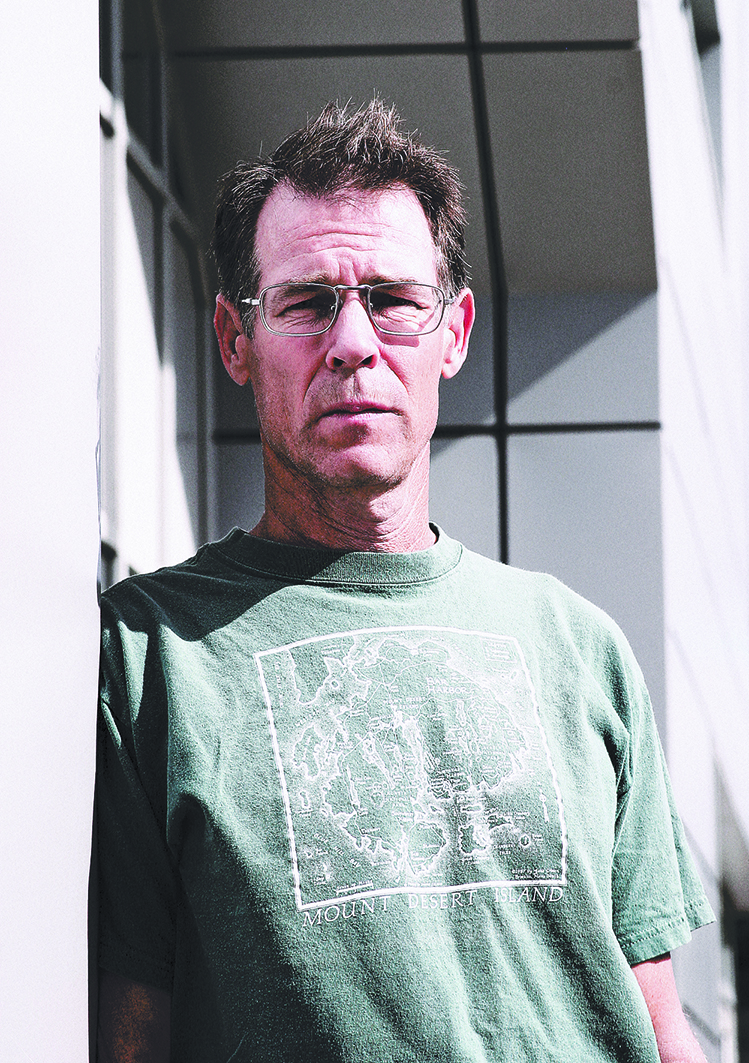

In other words, LeCompte, dark-haired, goateed, and on this day sporting a black hoodie, seems like a lot of bright, outdoorsy, and unabashedly geeky Northwest techies. Except for one thing. He’s planning to give it all up—the wind on his face, the rain in the air, his weekly get-togethers, and most definitely Oreo milkshakes—to go to a place that’s barren and possibly uninhabitable, devoid of even the most basic earthly delights, like breathable air, drinkable water, and anything resembling food.

In mid-February, a private Dutch outfit called Mars One announced that LeCompte was one of 100 finalists—out of a pool of 200,000 applicants from around the world—whom it had selected to go on a mission to Mars. It would be a one-way mission—meaning the rest of these fledgling astronauts’ lives, as long or short as they may be on the Red Planet, if they even get there alive. Mars One appears to be serious about this, as does LeCompte.

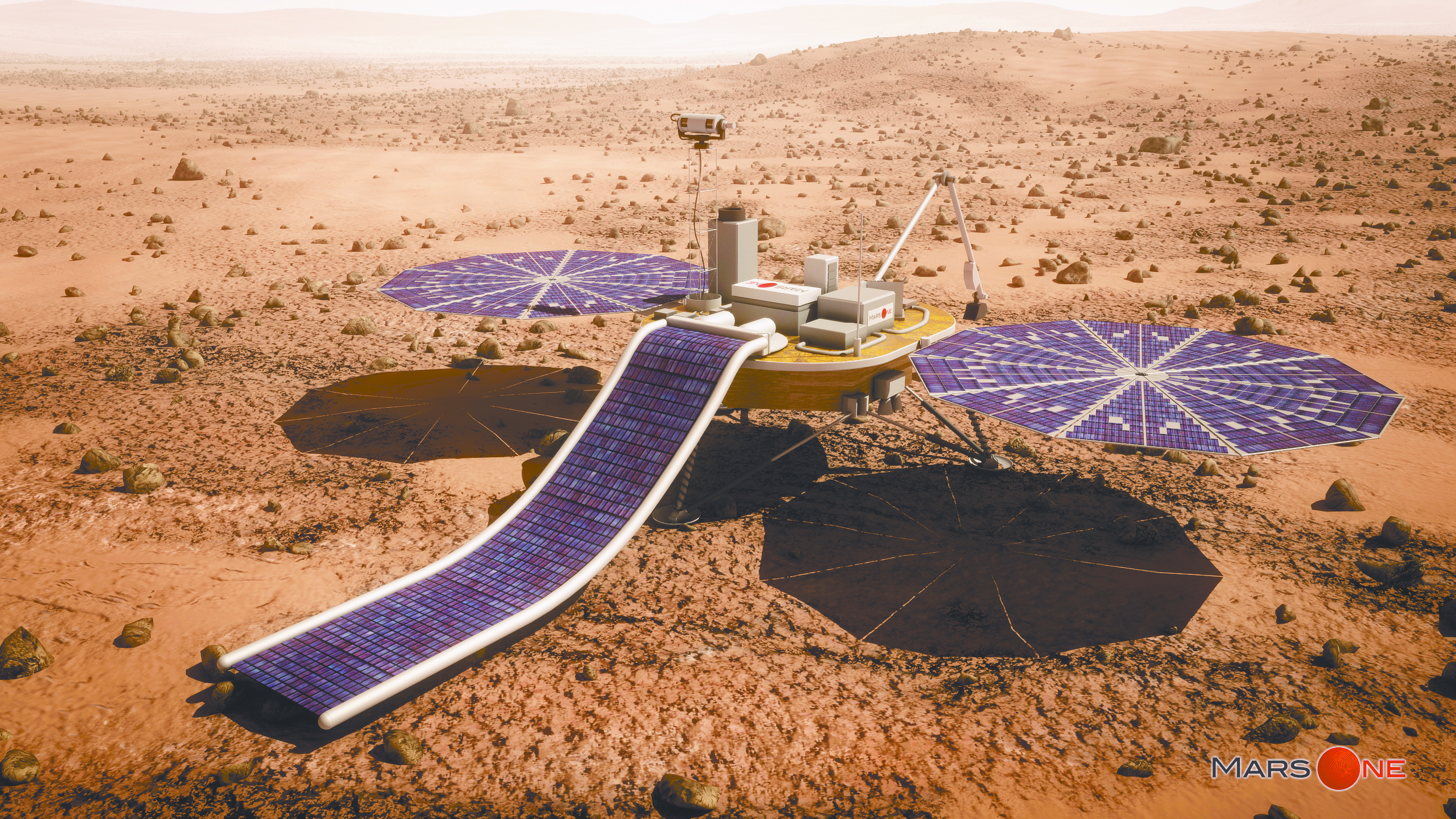

A couple of years ago he read an article about the mission. Mars One’s founder, Bas Lansdorp, an engineer and former wind-energy entrepreneur, had announced that his new enterprise intended to establish a permanent colony on the fourth planet from the sun, a place that has served as an endless source of fascination for Earthlings. As Mars One puts it on its website, “the next giant leap for humankind” is to expand into the universe, and there are “obvious technical advantages” in making it a one-way mission. Getting to Mars will be difficult enough without hauling all the equipment needed to launch a rocket back to Earth.

The article LeCompte read went on to say that Mars One was looking for 24 would-be astronauts and “aspiring Martians,” as the candidates came to call themselves on a Facebook page. The first four-person crew, consisting of two men and two women, would depart in 2024.

“Do I feel I could do something like that? Do I feel it’s worth it for me?” LeCompte says he asked himself. We’ve walked from Potbelly to a nearby Starbucks to eat lunch. The chatter at the sandwich shop was too loud for LeCompte, who likes to focus on the matter at hand.

“I’ve always been interested in fiction about people trying to survive hostile environments,” he says, explaining his eventual decision to apply to Mars One. He recalls loving the 1965 science-fiction classic Dune, in which Tacoma-born author Frank Herbert tells the tale of a young man whose family takes over a desert planet.

But he says that the “biggest thing” to contribute to his decision was his hopes for our species. “I don’t want humanity to be stuck on Earth,” he says. “I feel a big part of what makes us what we are is that we try to become more than what we are.”

He goes on to explain that our space missions to this point haven’t accomplished that, in part because they’re round-trip. Although he can’t quite articulate why, he believes that it’s important to “go somewhere and stay there.” And he holds that Mars is the best candidate. Unlike the Moon, it has a measurable atmosphere, even if oxygen is only a tiny part of it, the rest being mostly carbon dioxide. Mars also has ice—at its poles and underground—that theoretically could be turned into drinking water. And hey, at least it’s not a hellish fire of a planet that rains sulfuric acid, like Venus. Not at all. Mars’ average temperature is -81 F.

Not that he’s going to be getting outside much. Due to dangerous levels of radiation, he figures he’ll walk in the open maybe “a few hours every few days,” and only then in a spacesuit.

Unappealing as that may sound, a veritable Mars fever has broken out recently, especially in the Northwest, which has unexpectedly deep ties to space exploration efforts past and present. Mars One, in particular, has attracted not only a flood of applicants but some respected scientists. Among its “ambassadors” charged with spreading the word is a Dutch physicist and Nobel Prize winner named Gerard ’t Hooft. He recently got some press for stating that the mission might take exponentially longer than planned. His remarks added to the cascade of skepticism and scrutiny that has greeted Mars One in the last few months.

Yet, reached by phone from the Dutch town of Utrecht, ’t Hooft tells me that although he sees “the dangers and obstacles a bit more,” he still thinks the mission is a noble effort that will one day succeed. “I’m quite surprised how far they’ve gotten, actually.”

Then there’s Elon Musk, the charismatic entrepreneur who made a fortune as co-founder of Paypal and CEO of Tesla Motors and now heads SpaceX, one of a new breed of private space companies started by tech billionaires (including Paul Allen’s Stratolaunch Systems and Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin). Musk came to Seattle in January to announce the opening of a new SpaceX office in Redmond, which, he told a Seattle Center crowd, would build a satellite system to pay for his eventual goal: “a city on Mars.”

Even NASA, whose funding and ambition has waxed and waned since landing the first man on the Moon in 1969, has announced plans to take humans to Mars in the mid-2030s. This is a turnabout for the space agency. In 1981, when a group of graduate students organized a conference at the University of Colorado to discuss human exploration of the Red Planet, the subject was “taboo,” remembers Chris McKay, one of the graduate students, who now works as an astrobiologist at NASA’s Ames Research Center. His group became known as the “Mars Underground.”

One momentous question helped changed the official mind-set: Could there have once been life on Mars? For that matter, could life exist there still?

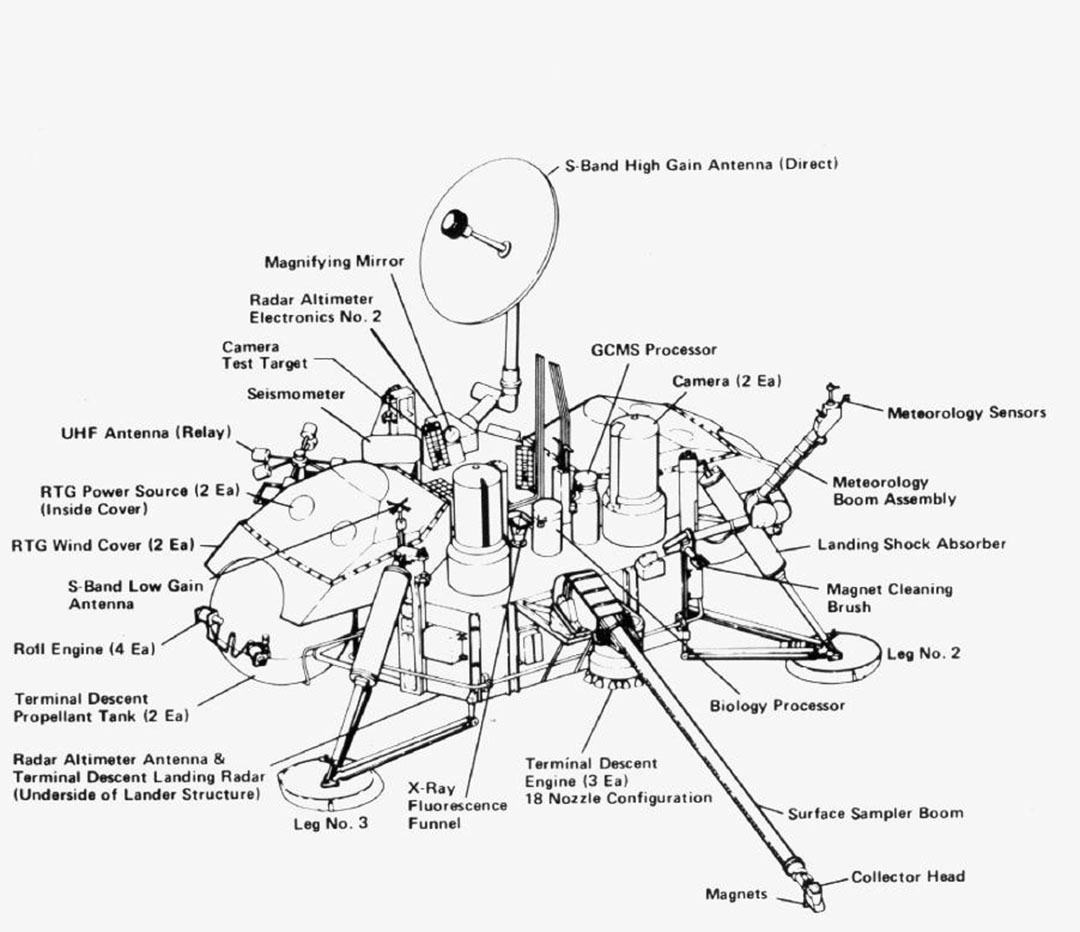

At approximately 4 a.m. on July 20, 1976, the first close-up pictures of Mars began to appear, pixel by pixel, on a screen at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Eleven-year-old Rachel Tillman was staying up late to watch them come in. In a nearby room was her dad, a University of Washington atmospheric-science professor named James Tillman, who played a key role in the mission.

“All of us were looking at these big rocks,” recalls Rachel Tillman, who now lives in Portland and heads the Viking Mars Missions Education and Preservation Project, which is creating a digital archive of documents, data, and oral histories related to the mission. The rocks were “bumpy and porous, not smooth like river rocks.” They cast shadows amid their own crags as well as on the ground. The images reminded her of the rugged desert landscape in Joshua Tree National Park in California, where her family liked to camp.

NASA already knew that Mars had striking geography. The space agency’s Mariner 9 mission, which five years earlier had sent probes to orbit the planet, took pictures of massive volcanoes. One, Olympus Mons, “would make Everest look like a mere hill,” according to UW planetary scientist David Catling. The images also captured the solar system’s biggest canyon—which on Earth would stretch from California to New York—and what appeared to be a former flood plain, suggesting that water had flowed on Mars billions of years ago.

But Mariner 9 was a flyover. Viking actually landed, enabling a wealth of detail. James Tillman set up a computer lab at UW that eventually received data directly from the landers. Speaking on a conference call with his daughter from a retirement home in Seattle, the now-82-year-old scientist recalls being surprised by the variability of great global dust storms. Viking saw two the first year and none the second. The mission also provided evidence to Tillman’s lab—despite the average freezing temperature—of “four seasons, just like us,” he says.

Viking had an even greater purpose than charting Mars’ geography and atmosphere. It was the first feasible search for life on the planet.

The subject had been a source of speculation for ages. In 1908, an amateur astronomer named Percival Lowell published a book that hypothesized about the origin of canals he and others thought they saw on Mars. The waterways were, he wrote, the creation of “intelligent creatures, alike to us in spirit, though not in form.” He was wrong. As NASA’s missions would later show, there were no canals.

Since then, the idea of life on Mars—whether native to the planet or imported—has inspired countless works of science fiction. Lynnwood author Greg Bear ticks off some of the classics: Edgar Rice Burroughs’ 1917 A Princess of Mars; Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles of 1950; the kitschy 1967 film Mars Needs Women. Bear, who himself has written about Mars several times, recently published War Dogs, in which Mars serves as a battlefield for human colonists fighting beings from another solar system. Bear says he used the planet as a proxy for the real-life battlefield of Iraq.

Mars has served a number of other functions in science fiction, and for that matter in our collective imagination. For some, it’s a refuge—the place we can go when our foolish, global-warming ways destroy Earth. For others, it’s grist for the ultimate adventure fantasy—an Antarctica for the space age.

Ironically, Kim Stanley Robinson, one of the most famous science-fiction authors to write about Mars, expresses impatience with such notions. Given the poisonous atmosphere, he says, speaking by phone from his home in California, he can’t understand why the lunacy of settling Mars—at least anytime in the next, say, 10,000 years—“isn’t just as obvious as the nose on your face.” Maybe it’s an Internet thing, he speculates, as “young people with too much time on their hands” peruse various Mars sites. (One, ExploreMarsNow.org, features an interactive design that allows users to virtually enter imagined future habitats on the planet. )

Yet Robinson’s Mars trilogy from the ’90s—Red Mars, Green Mars, and Blue Mars—contributed another way of imagining Mars: as a utopia. His novels, which he stresses are a “thought experiment,” not a road map, envision a planet where land is communal and environmental values reign. His description of Mars was not entirely a product of his imagination, however. Robinson says he was inspired by the Viking mission’s pictures. Here was a landscape that looked to him like the “American Southwest on steroids,” with “amazing mountains” that “looked both familiar and completely strange.”

While space exploration inspires science fiction, the reverse is also true. The interplay of the two realms, along with the tech sector, is long-standing and tremendous. When Robinson has a question about Mars for a novel, he says he calls NASA’s Chris McKay, who convenes a lunch seminar for him at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley. And on the day we speak in early March, Robinson is planning to deliver a talk about his views on Mars at SpaceX the following week.

Bear says he and his wife Astrid have gone to dinner with SpaceX’s Elon Musk, who sought the couple’s views on space-tourism pricing (a quarter-million dollars sounds about right, they all agreed, far below the going rate). The couple has also snagged a rare tour of Bezos’ Blue Origin facility in Kent, which is working on enabling “lower-cost” space travel. “Big, beautifully outfitted—a spaceship factory!” Bear enthuses.

Yet science has not yet aligned with science fiction, especially when it comes to life on Mars. Viking played a formative role on that point. When the landers arrived, they discovered no creatures, intelligent or otherwise, roaming the planet. Nor any plants. None. No trees, no flowers, no tumbleweed. And when the landers tested the soil for organic matter, none appeared.

“It was very disappointing to many,” says Rachel Tillman. “It shut down the Mars program for the next 20 years.”

Yet the soil had exhibited a reaction when tested. Essentially, it fizzed. What was that? Some thought it was a chemical reaction, but others suspected organisms at work.

Something even more important kept the idea of Martian life alive, according to McKay: our knowledge that the planet had once contained water. “Water is the essential requirement for life on Earth.”

So NASA eventually returned to Mars missions. And the agency found even more evidence of water. The Curiosity rover, on Mars since 2012, discovered ancient lake beds that once would have made excellent homes for microbes—the starter organisms for life. Meanwhile, a Science magazine article revealed just last month that analysis from observatories back on Earth suggest that the planet once had a vast ocean.

And even if living matter doesn’t exist on Mars, and never did, why not transplant life there? That’s the view of McKay, who is involved with planning future Mars missions as well as interpreting data from Curiosity. “If we take life as a thing we value, than spreading life around the universe is enhancing that value.”

McKay—who served on Mars One’s board of advisers until NASA told him that holding such a position with a private firm is verboten—goes one step further. “Our goal should be to enhance the richness and diversity of life.” What he means is that whatever we plant—ourselves, animals, or actual plants—“will take off on its own evolutionary trajectory.”

“Who knows what it will create?”

McKay’s dream is one thing. NASA’s actual plan is another. As he sees it, the agency doesn’t have a “clear path” to Mars. A lot needs to be figured out first—for instance, the impact on humans of a prolonged stay in space. NASA projects its first mission to Mars will take at least two years—four times the length of the typical stay at the International Space Station. Just getting to Mars would likely take six to eight months.

Unlike Mars One’s planned journey, NASA’s would be round-trip. No government agency could tolerate the risks of dispatching people into space forever. As ’t Hooft, the Dutch physicist, points out, Mars One doesn’t have that problem. “Nobody’s going to pay any tax for it,” he tells me. “It’s fine to ignore” naysayers.

Another thing Mars One is doing that a bureaucratic agency is unlikely to is pitching its mission as a reality-TV show. ’t Hooft predicts that it will be a “media spectacle.” After all, Mars is sexy—much sexier than the Moon. At least that’s what ’t Hooft says CEO Lansdorp told him when the physicist asked about the possibility of first colonizing the Moon, a mere three or four days’ journey. Mars One says a media contract will help it raise the projected $6 million needed for its venture. Yet a deal with the British TV production company Endemol fell through. In a company-produced video posted on the firm’s website on March 19, Lansdorp says Mars One is working with a new, unnamed production company—one that is still pitching broadcasters.

Meanwhile, Lansdorp said his organization had completed two investment rounds among unspecified financiers, the largest of which resulted in an agreement with a “consortium.” He conceded, however, that the relevant “paperwork” is “taking much longer than we expected.”

Consequently, he announced that Mars One is delaying the mission by two years, with the first astronauts now scheduled to depart in 2026.

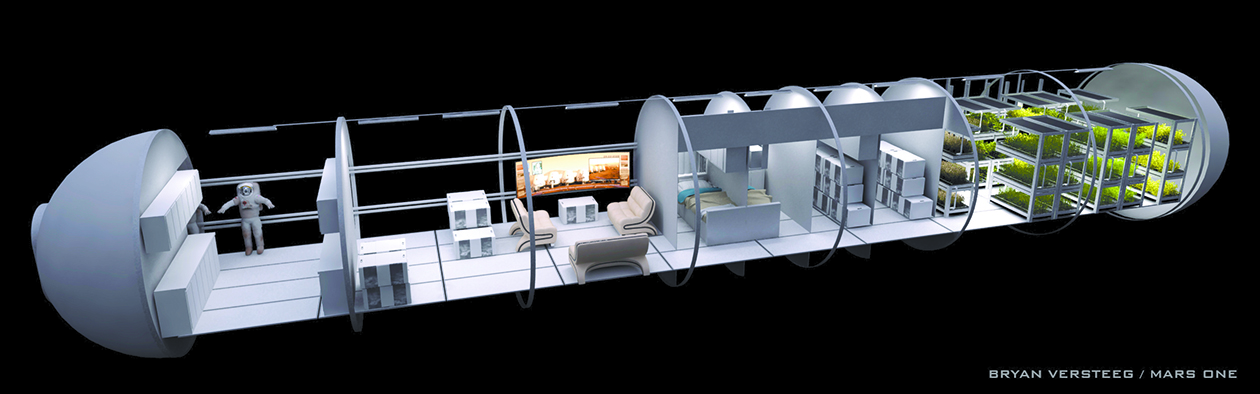

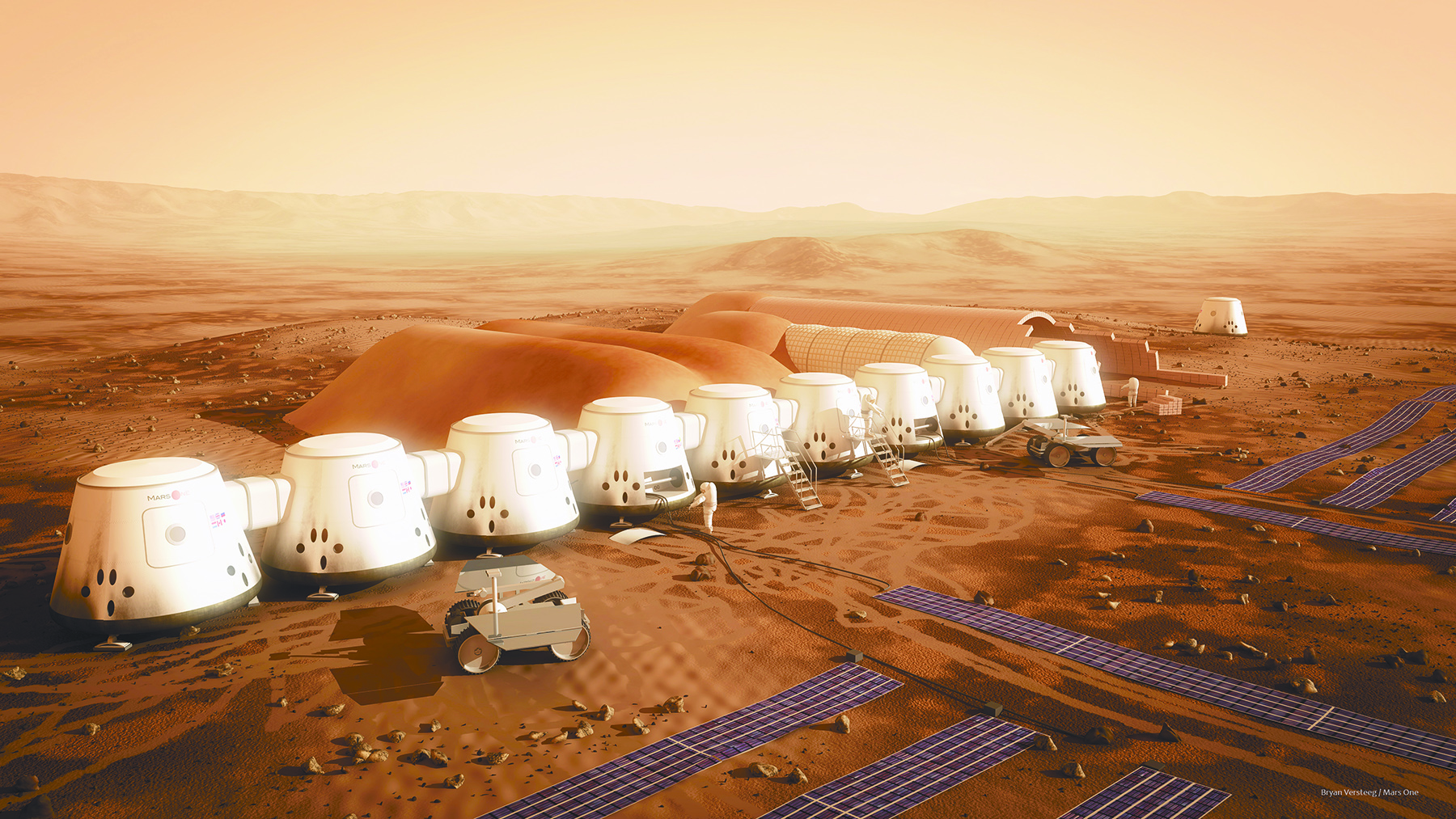

While it nails down its funding, Mars One, which calls itself a nonprofit, is pushing merchandise: $50 hoodies, $18 mugs, and a $85 laser-engraved miniature of a Mars One “outpost.” The colony is depicted as a series of connecting white huts—the lander modules—two of which have inflatable tubes sticking out of them: tubes intended to serve as the colony’s main living area, and where the aspiring Martians are supposed to grow their own food.

In mid-March, writer Elmo Keep published an article on the website Medium that accused Mars One of “ripping off” its astronaut applicants by awarding them “points” if they buy merchandise and make donations. The article quoted an e-mail written to applicants that suggested that they take money for press interviews and donate 75 percent of the profits to Mars One. (No sources were paid for this article.) In his recent video, a response to the Medium article and mounting criticism, Lansdorp said that any such donations are “not related at all” to the candidates’ prospects.

Perhaps. But getting swindled ranks as the least of the fledgling Martians’ potential problems. Just talk to Sydney Do. After hearing about Mars One, Do, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduate student, sat down with colleagues to study the organization’s plan.

Do, who studies aeronautics and astronautics, is far from cynical about space travel. The 28-year-old Australia native tells me that he came to the U.S. because his home country has no significant space program. He’s wanted to be a part of one ever since he was 5.

He wonders how it would feel to experience what astronauts call “the overview effect,” whereby you’re far enough away from Earth to see it as a whole. Apparently, he says, that “changes your entire perception.”

He’s already gotten a taste of what space would be like by flying in the so-called “vomit comet”—an aircraft that flies in a particular arc that allows those inside to feel weightless. “That was like being reborn,” Do says. “It was incredible—like you’re literally flying.”

He would like to go to Mars. “But I don’t personally see that happening anytime soon.” Which brings us to his and his colleagues’ analysis of the Mars One mission. “First off, we assumed that you could get to the surface.” This was no small assumption. As Do points out, there’s no technology yet available to take humans, as opposed to robots, to Mars.

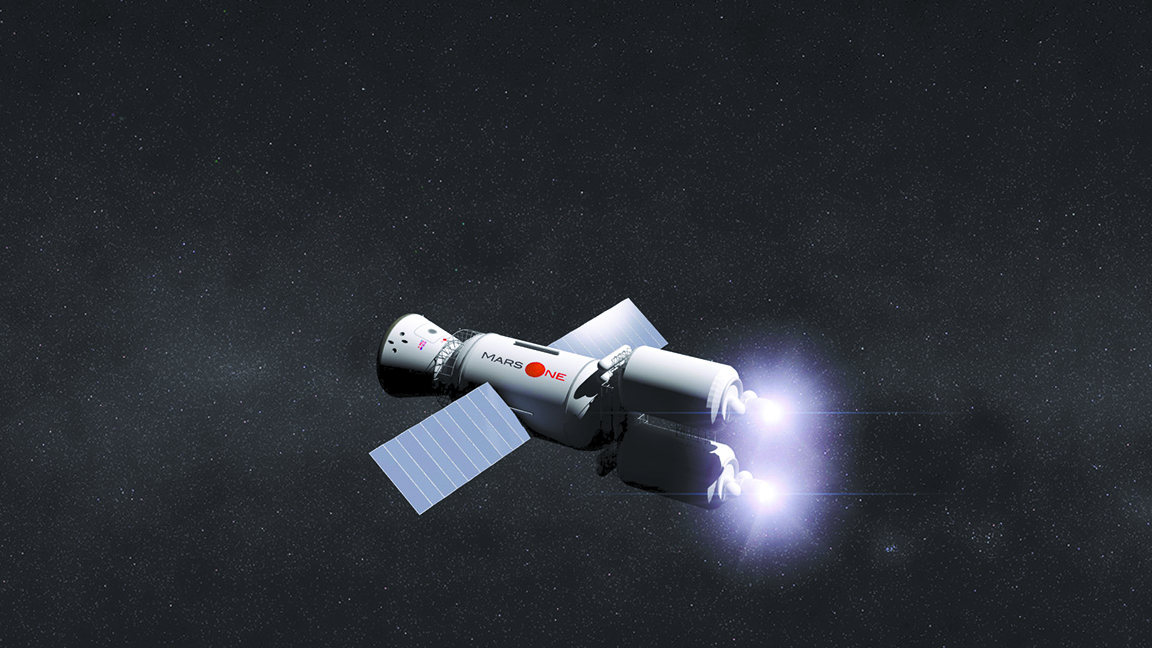

Musk, the SpaceX founder who hypes Mars colonization more than just about anyone, said as much when asked about Mars One last October at an MIT symposium. He noted that the Mars One illustrations he’s seen have its mission using both rockets and spacecraft (for carrying the crews) designed by SpaceX. “That’s cool, we’ll certainly sell them,” Musk said with an amused look on his face. Yet, he added, “I’d recommend waiting for the next generation of technology.” For one thing, the crew would be spending months on end in “something with the interior volume of an SUV.”

If they survived that and reached the vicinity of Mars, the crew would then need to land in one piece—another challenge. A spacecraft has to travel at extraordinary speed to get to Mars and something needs to “catch” it, Do explains. Whatever that thing is obviously needs to be more careful with humans than with robots. “You don’t want to go splat on the surface of Mars,” Do says.

But OK, say the crew lands safely. What are its members going to eat? Unless science figures out a way to grow food in Martian soil, which by the way is permeated with toxic salt, the colonists will subsist entirely on the plants they harvest inside their Martian living quarters—and perhaps, as some affiliated with Mars One have suggested, the insects they bring. To produce enough food for just the first crew of four, Do and his team calculated, the growing space would need to be four times larger than the 50 square meters Mars One initially planned.

After the MIT team published its findings in September, Mars One changed its design accordingly on its website. But that only exacerbates other problems detailed in the paper. Chief among them would be the dangerous level of oxygen released by the plants. “It would result in the crew suffocating,” Do explains. Mars One could tinker with the design again and separate growing and living areas. Or possibly technology could be developed to moderate the oxygen level. But all that means bigger modules, more equipment, and a stream of spare parts, driving costs to an unsustainable level, in the judgment of Do and his colleagues.

When we talk, Do plays out that scenario even further. “Say the company back on Earth goes bust.” Who, if anyone, he wonders, would pay for sending more spare parts to Mars? It’s not as though the Mars One folks can just hop on a rocket and come back. Even if they brought launch equipment with them, which they won’t, the trip is feasible only once every 26 months, due to the varying distance between Mars and Earth as they orbit the sun.

When you think about it, as many beyond MIT are now doing, the ethical and logistical questions are mind-blowing.

Scientists evince a push-pull as they contemplate human exploration and colonization of Mars. The result is that such missions seem at once more credible than you might have thought and utterly crazy.

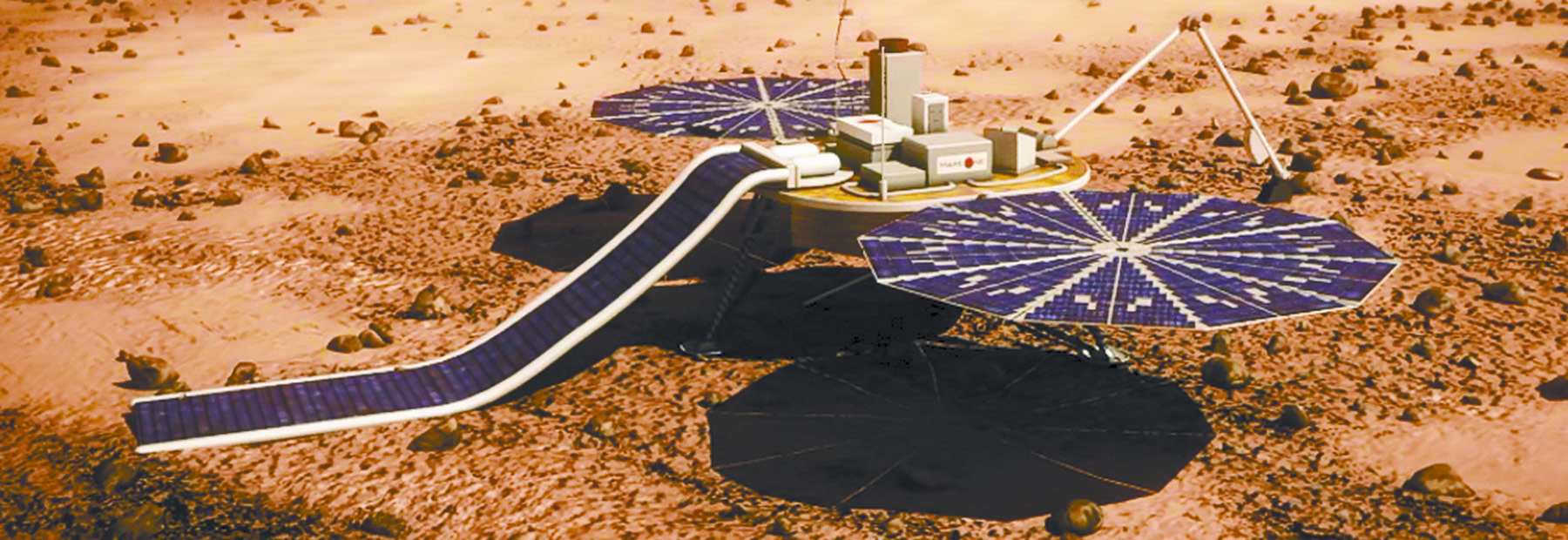

“I would be quite happy to work on the first human mission [to Mars],” says the UW’s Catling, speaking in his campus office, which boasts both a wall map and a globe of Mars. He’s been studying Mars since he was a graduate student at Oxford two decades ago, and participated in both the disastrous 1998 “polar crasher” to Mars (as it became known, after the lander did go splat on the surface) and the successful Phoenix mission a decade later.

While Phoenix and other robotic missions have sent back an enormous amount of information, “humans could do so much more,” Catling says, echoing an oft-heard rationale.

He also says he thinks it is possible that we could one day create a habitat suitable for humans on Mars. But since we don’t have one yet, he says he wouldn’t affiliate himself with Mars One. “I don’t want to be involved with killing somebody, which is really what a one-way mission is.”

Putting aside the obvious calamities for a minute, he wonders what would happen if somebody needed surgery. Or, he asks, “What happens if there’s a couple and one of them gets pregnant? You don’t have a midwife on hand. You don’t have an education system.” A child born on Mars would grow up in an environment with roughly 40 percent less gravity than Earth, he points out. We don’t know what effect that would have.

There are other unforeseen dangers.

James Tillman, the Viking mission veteran, says it would be “stunning, just stunning” if a mission were to discover life on Mars. But he also recognizes the possibility that such life could be dangerous—say, a virus unknown on Earth. “The idea that people could even be allowed to come back after being exposed to something like that . . . ” he muses, trailing off. If they were, he says, they should have to go to a facility that isolates people who have been exposed to biological warfare. “You’d want to stick them in there for a year or two or three.”

Norbert Kraft, the chief medical officer of Mars One, doesn’t sound concerned. “There are always risks. If you know what happens on Mars, then you don’t need to go there.” The Austrian native is speaking by phone from San Jose, Calif. That’s near NASA Ames, where an agency spokesperson confirms that Kraft once worked as a contractor on a joint project with the Federal Aviation Administration studying fatigue among air traffic controllers. That contract came to an end in late 2011. “It was exactly when Mars One approached me,” Kraft recounts.

His equanimity when it comes to the Dutch mission may relate to his need for a job, or it may have something to do with his unusual personality. The latter became apparent in 1999, when he was working for Japan’s space agency and opted to participate in a 110-day spaceship-simulation exercise in Moscow. “I had no problems to be in a ‘tin can,’ ” he tells me cheerfully, saying he kept himself occupied by “little things,” like making decorations for his crewmembers’ birthdays.

Other members of the crew, meanwhile, were going nuts. Two Russians got into a bloody fight, so traumatizing a Japanese member of the team that he quit early. A Canadian woman on board also had problems with the Russians—in particular one she accused of sexually harassing her.

Kraft chalks the problems up to culture clashes—a phenomenon that one might presume would also arise among Mars One’s crews, which are supposed to be international. The medical officer, who is in charge of picking the astronauts, says he’s screening candidates carefully. In video interviews, he relates, he asks them what they would do if after three years on Mars, they had the chance to come home. Would they go? “If they say yes . . . then they’re out.” That would convey an attitude of “me, me me,” he says, because how would the crew members who remained behind manage?

This doesn’t exactly address the question of culture clashes, though. Kraft says that will come in the next selection round, when candidates will be divided into teams and put in an “isolated environment.” Nor does the selection process Kraft describes address the full range of ethical issues involved, although he says he did ensure that none of the participants planned on starting a family in space anytime soon. And if accidents happened? Well, they are “mature people,” he says. “They are responsible for themselves.”

How would the child even be delivered? I ask. And what about other medical needs—for example a crew member getting cancer, a very real possibility given the level of radiation in space? “All applicants have to learn all professions,” he calmly replies. “Medicine, dentistry, geology . . . ” For eight to 10 years, he says, Mars One’s astronauts will train full-time at some yet-to-be-designated location.

For the more technical questions raised by Do and his colleagues, Kraft refers me to Lansdorp, who declines, via a company spokesperson, to make himself available. But Kraft, 52, says he’s confident enough in the mission to plan to go to Mars himself, with his wife, when they retire. He says a low-gravity environment alleviates pain caused by aging bones and joints.

As we talk for about an hour, I am acutely aware that I have way more access to Kraft than the people who are willing to risk their lives on the Mars One mission. According to LeCompte, the company scheduled 15 minutes for each video interview with Kraft. LeCompte’s ran short, just seven or eight minutes.

The only time I see LeCompte hesitate is when I ask him whether he feels funny about making such a big decision after such little interaction with Mars One. “A little,” he concedes. That’s why he says he’s trying to keep his eyes open as events develop. In particular, he is awaiting a feasibility study that Paragon Space Corporation was supposed to deliver to Mars One in early March. As of press time, the company had not made it public.

A couple of weeks after we meet, I call LeCompte to ask if he is having any second thoughts. “Not particularly,” he says. I ask him one more time if this is for real. “I hope I’m going to Mars,” he says. But, he allows, “In terms of whether or not I’m actually going to go, this may or may not succeed. An endeavor like this is a long shot.”

Anyway, he says, if Mars One doesn’t work out, he might just look into working at Musk’s new Redmond facility.

Actually, LeCompte could stay on the Microsoft campus and go to Mars—well, virtually, anyway. In January, the company unveiled technology that it had been secretly working on for years: a holographic device called HoloLens. It has a lot of applications, but one of the most fascinating is its use for scientific research on Mars, a project that Microsoft has been working on with NASA. Using images from Curiosity, Microsoft has created 3-D holographic images of the actual Mars landscape. With them, scientists in different locations can examine and analyze the geology together, with each seeing the same vivid images.

It’s another Mars Underground, if you will. The warren of rooms where HoloLens team members have been designing and testing the technology lies beneath the main floor of the Microsoft Visitors’ Center—an interesting place to keep a secret, note the team members who show me around one day in mid-March.

After being led into a white-walled room, I put on the HoloLens headset, and the space fills with light-filled images. Instantly I understand why Mars reminds people of American deserts. The ground, with just the faintest reddish tinge, is barren but not overwhelmingly bleak. The scattered, craggy rocks provide visual interest. The images are so sophisticated that I can look underneath one rock and see the crevices beneath.

Mainly, though, I’m struck by the mountains. These aren’t massive, like Olympic Mons. They’re human-scaled, gently undulating and bathed in a hazy light. They’re beautiful. For a few minutes, it doesn’t feel so crazy to want to hike them.

In fact, I can hardly believe, at this moment, that the planet is awash in dangerous air, salt, and radiation. It looks so familiar and alluring. And I realize it’s happened to me. However fleetingly, I’ve come down with Mars fever. E

nshapiro@seattleweekly.com