By happenstance, last weekend I finally got around to Seattle author Timothy Egan’s 2009 history The Big Burn, right about the same time a group of yahoos began occupying the visitor’s center at a wildlife refuge in Oregon.

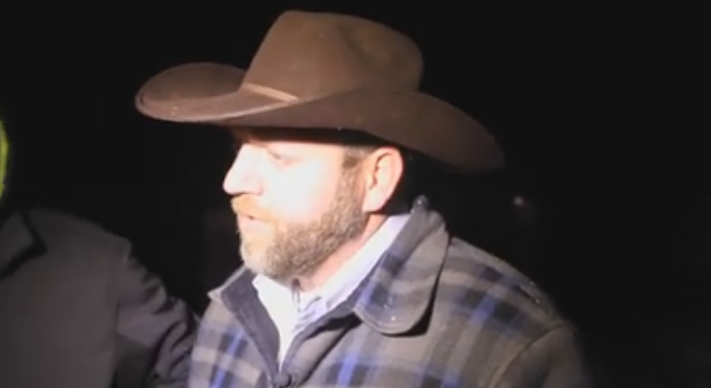

I say by happenstance because the first 100 pages or so of the book provide essential context to understanding the ideological fight that’s central to Ammon Bundy and his supporters’ grievance against the federal government’s management of Western land, that being that the federal government manages Western land at all.By Bundy’s telling, the feds took control of the land by unconstitutional means, and therefore have no right to enact environmental protections like those enjoyed on the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge that they are now encamped at. However, Bundy, as far as I can tell, leaves it at that, not delving into the history of how and why a small band of conservation minded government officials — led by President Teddy Roosevelt–created federal land as we now know it, using executive powers to pursue a then-radical vision of lands conservation in America.That’s where Egan comes in.The meat of The Big Burn is the 1910 forest fires that ravaged Western Montana and the Idaho Panhandle, which came to be a defining event in the history of the newly minted U.S. Forest Service and its firefighters.But before we can get to the fire, Egan recounts, in his expertly breezy way, how the U.S. Forest Service came to be in the first place. While that story does involve plenty of executive might that might make libertarian uneasy, it is nonetheless a history that lends little to recommend Bundy’s view of the West.The fact of the matter is that before Roosevelt acted, Western lands were largely controlled by barons of various stripes: Copper barons gouged the hills, timber barons denuded the forests, cattle barons ran herds on public grasslands without paying a nickel to the public for the grass.”So long as there were no trained professionals to watch the woods and grasslands, big money prevailed…,” Egan writes. “The General Land Office existed for one reason: to transfer public property to private hands…It was staffed by bureaucrats who neither knew nor cared for wild land in the West.”The idea of conservation struck many Western profiteers as a soft-minded concept dreamed up by Ivy Leaguers who’d never been to the West.Egan quotes copper baron William A. Clark’s view on preserving resources for future generations thusly: “Those who succeed us can well take care of themselves.”But Roosevelt had been to the West, running a ranch in the badlands and seeing first hand how much had already been lost of the American wilds. One of Roosevelt’s first actions when he won the 1904 election was to take steps to actually manage federal lands in way that took more into consideration than private enrichment. His point man on this project was Gifford Pinchot–for whom the wide swath of National Forest in Southwest Washington is now named.”It must not be forgotten,” Roosevelt told Pinchot, “that the forest reserves belong to all the people.”Here, then, a century before the Malheur occupation, we find the beating heart of the conflict.The argument coming out of the visitor’s center is that through federal stewardship, people have been barred from working the land. When people can’t work the earth, Bundy reasons, they become enslaved to the government. The solution, then, is to have federal land, including the refuge now occupied, handed over to local authorities.It makes for an OK soundbite, and really doesn’t sound too different than the back-to-the-land hippies that the media tends to be more sympathetic to. But you don’t have to scratch at it much to see that what Bundy is really advocating is a return to the free-for-all West that Egan describes and Roosevelt rightly put an end to.The Bundys themselves got into the fed-fighting business after the Bureau of Land Management decided to restrict grazing on BLM land to protect habitat for the the endangered desert tortoise. Like their forebears, the Bundys find the idea of conservation taking priority over economic interests as a sin against humanity. Trouble began around the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in the 1990s when refuge managers began fencing off grasslands to a nearby rancher, as was their right to do in the interest of operating a refuge (as it happens, the refuge was one Roosevelt himself created in his original push for habitat conservation).Above all, what The Big Burn demonstrates is that the standoff if Oregon is, at its core, a standoff over the core principles of environmental protection. It shows that while Roosevelt established the federal government’s strong hand in Western land policy quickly, he did not do it lightly. And it gives some prospect of what was averted when the federal government decided that land was not only there for profit.