As summer travelers make their way along the North Cascade Highway, the Skagit River is running high and fast, both from glacier melt in these rainless days and from the lowering of Gorge Lake by Seattle City Light to do repair work on a flood gate. The mountains that bracket the valley floor show clear patches where loggers lucky enough to find the work have taken the timber.

The Skagit Valley is known for tulips, eagles, salmon, and, to the east, mountains with spires so spectacular they are called “America’s Alps.” Anyone traveling to or from the mountains along the North Cascade Highway passes the town of Concrete, located at the confluence of the Baker and Skagit rivers. A sign on the now-unused police station at the end of Main Street reads, almost Zen-like, “Concrete: Center of the Known Universe.”

At its peak in the 1940s and 1950s, Concrete had a population of about 1,700, a movie house (it’s still there), a dozen or so saloons, and several bawdy houses. It was a company town run by Superior Cement. Workers mined high-quality limestone from a quarry on the town’s northeast edge.

The cement plant closed in 1969, leaving Concrete covered in gray dust. In the years since, the town’s population has shriveled to its present size, about 760. The old silos that once dumped cement powder into rail cars still stand as a symbol of its past. The town remains, however, the hub of the upper valley, offering travelers the only full-service grocery and hardware store and the last hard-liquor saloon before reaching Winthrop, 103 miles away on the east side of the Cascades.

For valley people who can find ways to work on the land, there is still logging, farming, or fishing. Others retire to it. Mostly there are those who commute to jobs “down below,” the colloquial name for the flatlands a few dozen miles to the west. “Down below” is not so much a description of the elevation change—only about 250 feet—but of a state of mind, a transition down-slope from what locals justifiably see as God’s Country to the land of Walmart, Costco, Home Depot, the Cascade Mall, and the Skagit County Courthouse in Mount Vernon.

More than 90 percent of the upper valley’s population is white, the rest Native American, Hispanic, black, and mixed-race. Differences among people tend to be more economic than ethnic—residents include everything from hand-to-mouth second-generation trailer-dwellers up to retired dot-commers living in $700,000 custom log homes, sometimes in the same neighborhood. Some are drawn by the natural splendor; others move to the upper valley to be left alone, putting distance between them and “down below.”

And while upper-valley residents may not all socialize, they tend to band together when they see a threat from the outside. It always seems to be the government or other forces from “down below” or beyond that stir the “Don’t tread on me” sentiment shared by many upper-valley folk.

Few incidents have riled the community like the one last February, when word reached the town that the school district and one of its most respected teachers were the focus of a complaint filed with the civil-rights division of the U.S. Department of Justice over comments the teacher made about Islamic terrorism.

What followed was an outbreak of fear and loathing that reached the outer edges of the grid, stoked by the more toxic regions of the Internet, where an Islamic-rights group’s “bullying” of a rural schoolteacher was widely condemned and anti-Islam groups found a rallying cry. By March the Thomas More Law Center, one of the nation’s most prominent defenders of “the religious freedom of Christians,” was involved. The small town of Concrete, removed and ensconced in the Washington wilds, had unwittingly found itself in the middle of a battle between world religions.

The Concrete School District serves an area much greater than the town of Concrete. Geographically it’s the state’s largest school district, drawing students from a 1,800-square-mile area that sprawls about 50 miles across, from just west of Concrete to the north and east almost to Ross Lake. The district’s population averages 2.53 persons per square mile. (Washington state averages 94.3 per square mile.) The district serves about 760 students.

By all accounts, Mary Janda was highly regarded in the district as a teacher, a favorite of the kids and respected in the community. She lives with her family farther upriver, just northeast of Marblemount, in a compound of buildings created by her woodworking husband and sons. Over her 20 years with the school district, there had never been a complaint about her, school officials say.

On October 29, 2012, Janda was leading the class in a discussion about bullying, when the topic veered from what kids do to other kids to the subject of Islamic terrorism. Several days earlier, the entire middle school had attended an anti-bullying assembly staged by “Rachel’s Challenge,” a program established in remembrance of one of the children killed in the Columbine, Colo., mass shooting in 1999.

During the discussion, Janda posed a question that would set the stage for the unpleasantness to come. As Janda explained later, she asked the class if they knew anything about Hitler, and said she was surprised at the middle-schoolers’ lack of awareness. She said she compared certain Islamist terror organizations to Hitler—all bullies because they used intimidation and murder to get their way.

The exact words that Mary Janda used in her classroom that day are still in dispute. In her version, she merely equated violent groups like Hamas and the Taliban with “bullying,” the topic of the day. But one 13-year-old student said she heard it differently—that her teacher was saying that all Muslims are taught from an early age to kill Jews and Christians.

Whatever Janda said in that class, she soon learned that the girl was the daughter of the only known Muslim from Concrete to the Cascade Divide. It looked like Janda had drawn the winning ticket in a bad-news lottery.

“The information I shared was from a former extremist group member who had been indoctrinated that to kill a Jew or a Christian would make him a martyr,” Janda wrote in a December 12 letter to district Superintendent Barbara Hawkings. “He was trained in this as a young teen, subsequently did murder people but subsequently changed his life. The point that I was attempting to make was the connection that people who intend on imposing their will on others are bullies, whether they be Nazis or others, whether they be students or adults.”

The girl’s version of the classroom discussion differed. On March 25, 2013, on local radio station KSVU, in the only media interview she would give, the girl said, “Mrs. Janda brought up that Hitler was like a bully in the way he treated the Jews, and then she compared Hitler to Muslims and Arabs by saying they both raised their children from birth to give themselves to what they believe in, whether it be death or just giving themselves spiritually.

“When I told her that I thought what she was saying was biased, she told me that I didn’t know what she was talking about and that she saw it in a video . . . I’d like to know what video she saw it in . . . that information is critical in a situation, but she just ended the conversation.”

District officials say that before the controversy erupted, Janda had informed them of her plan to retire at the end of the 2012–13 school year. But what happened in her middle-school classroom on October 29 set an unhappy tone for the remainder of her last year as a teacher in Concrete.

After the discussion at school, the girl went home and told her father, a recent convert to Islam. He didn’t like the sound of it, and took to the Internet. He found a website for the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), and located the Seattle branch of the Washington, D.C.-based organization that defends the civil rights of Muslims.

The father later admitted that he lacked the confidence to face Concrete school officials alone. He refused to be interviewed for this article, but despite his lack of cooperation, Seattle Weekly is not identifying him because of his fear of violent retaliation. He did join his daughter for the brief interview with KSVU.

“We had a choice to go meet with them at the school,” he said in the interview, “but I felt that a letter would be better because I didn’t want to be put on the spot like that, in front of everybody there telling me that I am wrong and my daughter’s a liar or misinterpreted something.”

CAIR’s involvement began simply enough. Jennifer Gist, the Washington chapter’s civil-rights coordinator, wrote a letter. “Dear Superintendent Hawkings,” her letter began. “We hope this letter reaches you in the best of health and spirits,” a standard greeting, it seems, for CAIR letters. Hawkings’ “spirits” were anything but lifted. Already overworked, she would spend dozens of hours in the coming months dealing with CAIR’s request for an investigation and its extensive public-records requests.

Hawkings responded to CAIR with a short letter informing the group that she found no wrongdoing in Janda’s classroom conduct, and that nothing included in the school’s curriculum corresponded to Janda’s alleged classroom remarks. She had taken Janda at her word that she had not intended to suggest that all Muslims were potential terrorists. However, Hawkings, in a later interview, said that she did advise Janda that it was not a good idea to bring Islamic terrorism into the bullying discussion.

Meanwhile, Janda’s explanation about sharing testimony from a former terrorist caught the attention of Jeff Siddiqui, a Muslim community activist and naturalized American citizen living in Lynnwood. He thought Janda’s description of the former terrorist had a familiar ring.

“I am willing to bet this ‘former extremist group member’ portrayed by Ms. Janda, is no other than Walid Shoebat who has made his career as a Muslim-basher and has been discredited by many reliable sources,” Siddiqui wrote in an e-mail sent to a number of groups, including the school district.

Siddiqui speculated that Janda may have been exposed to a “grotesquely anti-Muslim” video entitled Obsession: Radical Islam’s War Against the West. The video, funded by a conservative group called the Clarion Fund, has been widely distributed. Shoebat was unmasked by CNN in a 2011 investigative project that showed that none of his claims about being a former terrorist were credible.

In her response to Superintendent Hawkings, Janda didn’t say if the information she’d shared with the class had come from a video, something the student had emphasized in her account.Hawkings did not ask Janda to identify the former “terrorist” she had cited in her letter to the Superintendent, or the source of the information.

The student’s father was not satisfied with Hawkings’ explanation for Janda’s remarks, but he was also still unwilling to meet with school-district officials, Gist said. Thus, without a single face-to-face meeting among the parties to the dispute, CAIR issued a press release on February 19 about the Justice Department filing that lifted the controversy to a new phase approaching ideological warfare. The release identified Mary Janda by name, and presented the student’s allegations as an undisputed fact. It lit a firestorm of community outrage, with people up and down the valley rising to the defense of Janda, one of their own. Conservative regions of the Internet, too, were ablaze.

“Islamists bully teacher in rural America,” said one website.

“CAIR Bullies Teacher for Calling Taliban and Hamas Bullies,” said another.

Eric Archuletta watched as the controversy enveloped Concrete and much of the upriver community. Although he lives in Arlington, he became familiar with Concrete a couple of years before when working on a project for his master’s degree in community planning at Antioch University in Seattle.

Archuletta, a husky man with soulful eyes, says he was drawn to Concrete because of his interest in building sustainable rural communities. Born in Oahu, Archuletta says he was saddened to see the disappearance of the sugar-cane culture that had sustained his home islands for over a century. He saw a similar plight in Concrete.

Archuletta and a few others formed the Imagine Concrete Foundation, a community-improvement organization. Jason Miller—publisher of the monthly Concrete Herald, town councilman, and current mayoral candidate running against incumbent Judd Wilkins—serves as its president, with Archuletta as vice president. So far the group’s marquee project has been a community garden, with neatly arranged raised plant beds, timber supplied by a local cedar-salvage company, and each fencepost adorned with a gaily colored birdhouse. Archuletta refers to the garden as the “crown jewel” of Imagine Concrete’s efforts.

“We needed to be more proactive in this town, rather than always being reactive,” Miller said recently, giving Archuletta credit for the idea for the organization.

Shortly after CAIR’s press release about Janda came out, Archuletta and about 10 others met at Miller’s house in Concrete. Miller insists that he hosted the meeting so he could keep in the loop as a journalist, although he agreed with the effort that resulted from it.

Archuletta says he hadn’t heard of CAIR before Feb. 19. So, like the Muslim father of Janda’s student, he hit the Internet, which bulged with information, as well as misinformation, about CAIR. Some of the entries linked CAIR to Hamas, on the FBI’s list of terrorist groups largely due to its history of launching rockets from Gaza into Israel. As he perused the Internet, Archuletta came across an organization calling itself “ACT! for America.” Its website offered dire warnings about “radical” Islamist activities right here in the U.S. Among them:

“Followers of radical Islam have declared jihad against Christians, Jews, Hindus, Sikhs, non-Muslims, and secularists—simply because they regard us as infidels. They even target Muslims whom they regard as insufficiently pure.

“Tens of thousands of Islamic militants now reside in America, operating in sleeper cells, attending our colleges and universities, engaging in influence operations aimed at the media and government. They are here—today. Many have been here for years. Waiting. Preparing.”

“Waiting. Preparing.” It sounded pretty scary to Archuletta. He found that ACT! had a Washington chapter, based in Kent and headed by Kerry Hooks, who like him was a 20-year Navy veteran. He called Hooks, and the next stage in the evolving drama was set.

“I didn’t do this because I have anything against Muslims,” Archuletta says. “I did it to help Mary”—even though he had no prior acquaintance with Janda, he says.

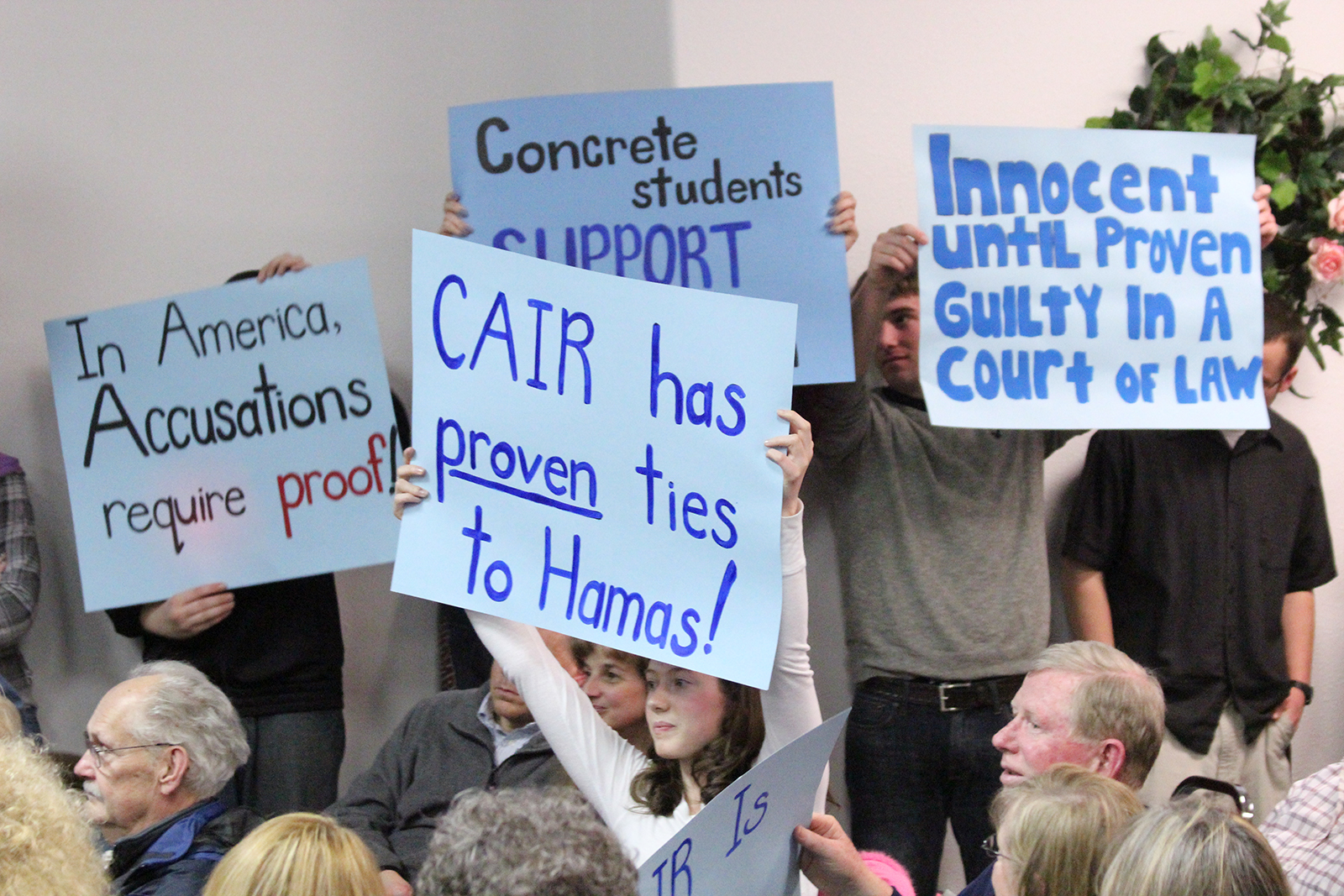

Archuletta arranged for the use of the Concrete Assembly of God Church, and for Hooks to come to the town to “educate” people about CAIR. On the evening of March 19, several hundred people descended on Concrete. Many came from far out of town, drawn by the anti-CAIR invective on the Web and what they perceived to be the group’s “bullying” of a well-respected country school teacher. Hooks addressed the crowd, which overflowed into the church parking lot.

“Who are we?” she intoned. “This is what we are not. We are not a hate group. We don’t hate anyone. We don’t condone acts of violence anywhere. We don’t fearmonger when we expose terror.”

Scoffing at CAIR’s offer to provide educational assistance on Islam to the school district, Hooks hooted to much cheering and applause. “CAIR implies that you are too stupid to understand Islam,” she said, “and they will come in and teach it to you.” Hooks declared that “radical” Islamists plan to impose Shariah law on America, supplanting the U.S. Constitution—a frequent charge in Islamophobic circles. Muslim scholars say that Shariah is not so much a law per se as a moral and religious code that guides the conduct and affairs of Muslims.

ACT! and other anti-Islamist groups have long claimed that American courts have already begun to recognize Shariah, which legal scholars dismiss as absurd fearmongering. Clark Lombardi, assistant law professor at the University of Washington and an expert on Shariah, says he has never found any of the examples cited by such groups to be true. He says some immigrants have tried to get courts to accept Shariah-based decisions from courts in Muslim countries, especially in family law, but without success. He said as far as he knows, all such cases in U.S. courts have been adjudicated according to American laws.

As the March 19 meeting wore on, it seemed to John Boggs that neither Hooks nor the crowd were making much distinction between “good” Muslims and “bad” Muslims. The meeting had a distinct religious tone that moved Boggs to comment later on a local website.

Boggs, a military retiree living near Concrete, has been active in Imagine Concrete as well as with the Concrete Heritage Museum. He was among the few locals trying to convince people to keep an open mind on the Janda matter. Boggs wrote that while some of Janda’s supporters claimed that “CAIR and Muslims in general wished to impose Shariah law on America,” her supporters seemed to “endorse bringing their own narrow version of religion into our public schools at the exclusion of any others.”

Boggs had stepped in it for sure. He found himself vilified on the Web as well as in the letters section of Miller’s newspaper. One writer accused him of “hyperbole” that could have a “polarizing effect” on the town. Thus far there is no sign of polarization; support in the upper valley for Janda is pretty much universal.

But few knew that Boggs had also written to CAIR criticizing the group for its public accusation of Janda, suggesting that an apology was in order. There was no apology, but CAIR did reissue the press release, inserting the word “alleged” in the portion concerning the charges against her. Arsalan Bukhari—a Seattle University graduate who with Gist is one of CAIR-Washington’s two paid staff members—did say later that he “regretted” the omission.

If Mary Janda didn’t volunteer for the angry debate over words and Islamic designs on American jihad, she was fully on board by March. Her role was cemented when she accepted legal assistance from the Thomas More Law Center, which on its website bills itself as “battle-ready to defend America.” The center says that it “defends and promotes America’s Judeo-Christian heritage and moral values, including the religious freedom of Christians, time-honored family values, and the sanctity of human life.”

“We’ve been representing Mary Janda since March, somewhat behind the scenes,” says Richard Thompson, the Center’s president and chief legal counsel. “We’re sitting back and waiting to see what happens with the allegations against this teacher.”

The Center provides free legal services to parties it believes are being persecuted for their Christian beliefs. It has taken on some high-profile cases, and won many of them. Thomas More lawyers recently prevailed in a federal lawsuit against the U.S. Health and Human Services Department that could have a big impact on the application of Obamacare. A federal judge ruled that the government could not force the operators of a business to provide health insurance to employees that violated the owners’ religious convictions against abortion and assisted suicide.

The Center also has taken the case of Army Lt. Col. Matthew Cooley, relieved of his teaching position last year at the Joint Forces Staff College in Norfolk, Va., for alleged anti-Islamic statements. A May 2012 article in Army Times said that Cooley had been teaching that “America’s enemy is Islam in general, not just terrorists, and suggesting that the country might ultimately have to obliterate the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina without regard for civilian deaths, following World War II precedents of the nuclear attack on Hiroshima or the Allied firebombing of Dresden.”

Thompson told Seattle Weekly that Dooley’s words had been twisted out of context, and that he had been unfairly targeted by higher-level officials afraid of reaction from the Muslim community. Not that he disagrees with what Dooley allegedly said. Thompson is among those convinced that the aim of Islam is to seize control of the American government and impose Shariah in place of the Constitution. Asked how a group comprising less than 2 percent of the population could accomplish such a thing, he offers an explanation that echoes recent allegations by conspiracy theorist and Congresswoman Michele Bachmann: “Small elite groups can take control of the government.”

On a warm Saturday afternoon in June, the Eastside Islamic Center and mosque had opened its doors to guests. The center’s annual open house is part of its membership’s ongoing effort to reach out to its non-Muslim neighbors. After slipping off their shoes, visitors entered the eight-sided enclosure to hear about Islam.

Imam Fazal Hassan describes the center’s approach to Islam as “moderate” Sunni. “Most of our members here are in high tech,” Hassan says.

The high tech industry has attracted thousands of Southeast Asians to the Puget Sound area, with about 1,700 working at Microsoft alone.

Zeesham Baqui, a 29-year-old Pakistani program manager at Microsoft, sat in the afternoon sun with his 5-year-old son as volunteers began turning out plates of tandoori chicken for the guests. Baqui has been living in Bellevue since 2006 and enjoys good relations with his neighbors.

“As soon as you have a human connection, a lot of those misconceptions [about Islam] go away,” he says.

But when issues arise, CAIR may step in.

CAIR’s two staff members, Bukhari and Gist, make something of an odd couple. The bearded Bukhari is soft-spoken and reserved, always neatly attired in suit and tie. He has been in Seattle since 1990. Gist, born and raised a Baptist in Colorado, is a 2010 graduate of Seattle Pacific University. She looks more the millennial, sporting a close-cropped haircut and a nose ring.

They are a tough team. Countering allegations of CAIR’s so-called “bullying,” Bukhari and Gist say that it is Muslims in America who feel constantly vulnerable, amid rising anti-Muslim sentiment stoked by extremists in print and on the Web. They make no apologies for being aggressive in defense of Muslim civil rights. They cite a spate of anti-Muslim incidents from the past few years, much of them inspired by the hate spewed on the Internet.

• A Muslim family visiting Seattle Center was recently accosted by a man who threatened to get a gun and kill them. He was arrested, and CAIR has demanded that he be prosecuted “to the full extent of the law.”

• Nine members of the Eastside Islamic Center, all college students, last September drove to Lake Chelan for a day of jet-skiing. When they returned to the parking lot, they found racist slurs scratched into the paint of one of the vehicles, including terms like “sand nigger” and “doon coon.” Although they reported the incident to police, there were no witnesses or other information on which to base an investigation.

• Two Somali women were assaulted in 2010 at a Tukwila gas station by a woman who called them “suicide bombers” and told them to “go back to your country.” The incident was recorded on the station’s surveillance camera. The woman was arrested and charged with assault.

“There have been countless other stories of hate crimes, including violent murders of people because they are perceived by their attackers to be Muslim,” Bukhari and Gist wrote in an e-mail to Seattle Weekly. “Due to this, it is imperative that organizations like CAIR defend the civil rights and liberties of American Muslims and respond to allegations of defamation even in situations that many may perceive to be ‘less severe.’ ”

That includes things said in a faraway rural classroom.

Gist and Bukhari surveyed the terrain in the aftermath of the March 19 ACT! meeting and made a decision. They would go to Concrete and “dialogue” with the residents. And just five days later there they were, sitting in a room at the Concrete Community Center with about 60 locals—some seeming willing to listen, but most radiating hostility.

One local gave the two CAIR workers credit for “having the guts” to come and face the community. Questions flew at the pair, some related to the persistent Web-driven claim that CAIR was founded by a supporter of the terrorist group Hamas. Not true, they said: Comments by a founder were taken out of context by bloggers who oppose CAIR’s mission, which is to defend American Muslims from discrimination.

At one point a man with long gray hair and a flowing beard, wearing a motorcycle jacket, interrupted the discussion. “Does everyone agree that Concrete was doing fine before these people got here?” he called out. There were murmurs of “yes,” with nodding heads. “Will Concrete be doing fine after they leave?” Another chorus of “Yes” followed.

“Get behind me, Satan,” the man said, adding “Amen” as he headed out the door.

Meanwhile, up in Marblemount, at the North Cascade Community Church, Pastor Dave Nichols and his wife Faye work to keep their twice-monthly food-bank distributions going. “There’s a lot of need up here,” says Nichols, who counts Mary Janda among his parishioners. The valley, for all its natural splendor, does have pockets of poverty.

The church is still an Assembly of God congregation, but Nichols says they changed the name to give it a more generic appeal, to be more open to the community as a whole. Assemblies are the world’s largest Pentecostal denomination, its adherents believing in the Bible as the infallible word of God, baptism by immersion and the speaking in tongues as an expression of the Holy Spirit.

Nichols greets a reporter in front of his modest church building, with graying white asphalt siding and an old van parked in front. He carries a copy of a book entitled Muslim Mafia: Inside the Secret Underworld That’s Conspiring to Islamize America. “I don’t see how anybody could read this book and not be alarmed about what CAIR is doing,” he says. “You should read it.”

The book was written by a man, P. David Gaubatz, whose son, Chris, pretended to be a recent Muslim convert to get an internship in CAIR’s Washington, D.C., office. Over six months he copied thousands of documents that were supposed to have been shredded. The book concludes that CAIR is part of an elaborate conspiracy to force Islam and Shariah on America.

Critics of the book have said that the big “revelation” is nothing more than CAIR’s determination to lobby Congress and increase Muslim voter registration through grass-roots efforts. The darker conclusions, they say, are the result of paranoid dot-connecting. But the book has clearly taken hold among those, like Pastor Nichols, who see Islam as a threat.

Nichols adores Janda, whom he calls “a jewel among jewels.” She teaches Sunday school and volunteers in the community, especially working with kids. He leaves no doubt that she is a devout member of his congregation. But he says she would never allow her Christian beliefs to color her responsibilities as a teacher.

As midsummer approaches, there has been no word from the Justice Department. The agency has been known to take many months to investigate civil-rights complaints. While they wait, the community continues to simmer.

Still, some in the area hope to find a middle way through the controversy. Linda Jordan, a psychology instructor at Skagit Valley College, moved to a small ranch in the Marblemount area 20 years ago after a career as a King County deputy prosecutor. Jordan said she has known Janda for years, and has “the utmost respect” for her. But she added that she is concerned about the student and her father.

“Do we want to be talking about conspiracy theories and Hamas and the Taliban?” she asks. “I don’t think Concrete is in danger of that. But we are in danger of something. That is, that right now we have a teacher who is ending her career with this on her record. We have a student who does not feel safe to go to school now, and she’s going to have to leave the district. We have a father who believes in the Muslim faith, and did not feel that he was safe enough to go to our school system and say, ‘I’ve got a problem.’ Is there a way to dial this back, bring it back into our community and deal with what’s important?”

For now, the answer to Jordan’s question appears to be “No.”