As a crusading public defender who has long championed police reform, Lisa Daugaard is the kind of person you might think would be celebrating the purported housecleaning within the Seattle Police Department over the past month. In fact, she is not.

“The members of the command staff who have done the most to try to fix things are now gone, and not gone in a good way—in a cloud of disfavor,” she says.

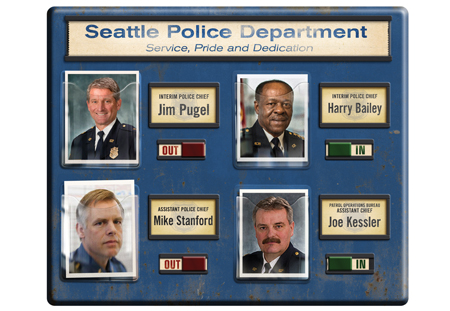

She’s referring, in large part, to the reassignment of interim chief James Pugel and the retirement of assistant chief Mike Sanford, both widely regarded as committed to the reforms ushered in by the Department of Justice’s findings, in 2011, of a pattern of excessive force within SPD. In a December report that otherwise blasted SPD leaders for resistance, both men were singled out for praise by Merrick Bobb, the court-appointed monitor of the department’s compliance with a DOJ settlement agreement.

In addition to that, Daugaard notes Pugel’s international reputation for “innovative policing practices,” especially his work on programs that address the health issues behind infractions committed by drug addicts and the mentally ill. That work resulted in Pugel’s invitation to Poland last month to speak with officials looking to follow Seattle’s example. As for Sanford, Daugaard says he “was a consistent leader in support of changing problematic police practices”—like an arguably oppressive trespass policy—even before DOJ-mandated changes.

Yet days after taking office in January, Mayor Ed Murray replaced Pugel as interim chief with then-retired assistant chief Harry Bailey. At the time, Murray said he did so to allow Pugel to compete for the permanent chief’s role. A search for a new chief is on a fast track to be completed by April.

Pugel’s fall from grace became apparent, however, when he was removed from headquarters and relegated to a basement office in an old narcotics facility on Airport Way. Then, last week, Bailey called Pugel into the chief’s office and gave him the choice of retiring or accepting a demotion to the rank of captain. Pugel is reportedly still considering his options.

Meanwhile, Sanford suddenly retired last month at age 53. Sanford was not exactly forced out, but according to police sources it had been made clear to him that he was no longer welcome.

The official line is that these changes, as well as the dizzying array of other staffing shakeups over the past month that have resulted in a near-complete turnover in the command staff, demonstrate to the public “that we are serious about change,” in the words of Bruce Harrell, chair of Seattle City Council’s public safety committee. “No one’s entitled to anything,” he says.

But a different picture emerges from interviews with multiple sources both inside and outside SPD. Many share Daugaard’s concerns, with several adding that some of the most influential forces within the department now are ones that have long resisted reform. In particular, sources cited the apparent power of the department’s two unions, the Seattle Police Officers’ Guild and The Seattle Police Management Association. The unions have in the past objected to the DOJ findings. Last year, both unions sued to block aspects of the monitor’s reform plan, and SPOG in particular has vociferously criticized the DOJ findings.

Some observers now speak of a union “coup.”

“I wish I had the power that everyone thinks I do,” responds Rich O’Neill, who is retiring as guild president later this month after many years in the position. SPMA president Eric Sano calls the speculation “totally false.” Both also insist that they are completely behind reform and just want to see it carried out as quickly as possible.

Whatever the unions’ views on reform, it is likely that other, more personal, factors are also at work. One department insider, who like many interviewed for this story spoke on condition of anonymity, says people are using the current turmoil as an opportunity to “settle scores” and “get themselves and their buddies” in power, with the hope that “it will stick when a new chief comes in.”

“I feel like I’ve fallen down the rabbit hole,” says the insider.

Bailey is a respected figure who carries particular clout in minority communities. Former mayor Mike McGinn hired Bailey, who is African American, to work on outreach, seeking a better relationship between those communities and police. Los Angeles civil-rights lawyer Connie Rice, also brought into the reform effort by McGinn, calls Bailey “enormously wise.”

Yet, says another SPD source: “I knew Harry would come with the unions.” Bailey is said to be particularly close to Joe Kessler, who until last month served as vice-president of SPMA. He gave up his union post when Bailey, a week after taking the SPD reins, promoted Kessler to the rank of assistant chief. Some go so far as to say that it is Kessler who is now really “calling the shots,” as another police source puts it. Neither Bailey nor Kessler responded to requests for comment.

Both SPOG and SPMA make no bones about their enthusiasm for Bailey, or for the way things are going generally. Declaring himself “excited” by the changes, SPMA’s Sano says that Bailey’s 35 years of service have given him a deep knowledge of the department.

O’Neill, of SPOG, notes that Bailey got a standing ovation at a packed membership meeting last week. In that meeting, Bailey expressed his pride in the rank-and-file and spoke about “getting back to basics,” which included wearing a clean and pressed uniform, according to O’Neill.

Union support may have something to do with why Bailey got the job in the first place. O’Neill and Sano acknowledge that Bailey was among the names they suggested to Murray as a possible replacement for Pugel. Sano adds that he and other union officials have, in meetings with the mayor, “fully vetted” planned changes.

During the mayoral campaign, Murray was endorsed by both police unions. “When someone crosses over and gives a big endorsement, you got to pay that back somehow,” observes a former city official.

Murray’s office said he was not available for comment on this story. Tina Podlodowski, the mayor’s top police adviser, does not comment directly when asked about union influence. Nor will she discuss the staffing shakeups, exactly. But she invites a comparison of SPD before and after the recent changes. “See if you think the people in charge were really trying to do reform,” she says. What shows they were not was the way they “structured” those efforts, she argues: Namely, she says, they put only four people into a unit set up to monitor compliance with the settlement agreement.

In contrast, Bailey last week announced a new Compliance and Professional Standards bureau that, according to Podlodowski, will comprise some 50 people. Also, the bureau will be headed by an assistant chief, rather than a civilian, as was the case in the old unit. Those changes are “a huge difference,” Podlodowski says. “It’s also the kind of thing that doesn’t become personality-dependent.”

It’s difficult to compare the numbers because the new bureau is taking in branches of the department not previously under the umbrella of the old compliance unit. But if the change is as significant as Podlodowski says it is, that was not well communicated at a press conference last week, in which Bailey spent a good portion of the time declining to answer questions about the command-staff upheavals.

Some see it as no coincidence that the losers in SPD’s current power battles have run afoul of union figures.

Sean Whitcomb, the department’s longtime public-affairs director, is among those who have been sidelined of late. According to sources, he is facing several internal complaints, including one that he discriminated against a member of his staff who, at last summer’s Hempfest, didn’t want to hand out bags of Doritos bearing stickers explaining the state’s recreational marijuana law. Whitcomb declined to comment.

The nationally reported Doritos stunt symbolized SPD’s openness to the marijuana-legalization initiative passed in 2012. Whitcomb led the charge in communicating that message, as well as recent efforts to make the department more transparent. As a result of the discrimination complaint, however, he was displaced from headquarters and assigned to work in the city’s emergency operations center.

The complaints arose only after Whitcomb himself filed a complaint against Ron Smith, SPOG’s secretary treasurer who is set to take over as president later this month. Whitcomb had reported a Facebook comment by Smith, in relation to Hempfest, which the public-affairs head viewed as threatening. Smith says “no reasonable person” would have viewed it as such, but declines to say exactly what he wrote. The Office of Professional Accountability has determined Whitcomb’s complaint to be unfounded, adds Smith, who also “definitively” denies instigating retaliatory complaints.

Another case in point: Sanford is said to be vehemently disliked by former SPMA vice-president Kessler. Well before his recent promotion to assistant chief by Bailey, Kessler was a voluble and popular SPD veteran who shone as captain of the Southwest Precinct but fell out of favor with the top brass after taking over the higher-profile West Precinct, which encompasses downtown. There was a perception that he was foot-dragging on a number of innovations, including the Law Enforcement Assisted Division program (LEAD), which takes the kind of public-health approach Pugel has championed. Sanford broke the news to Kessler that he was being yanked from the prestigious West posting. (He eventually went back to being captain of Southwest.)

Shortly afterward came the infamous May Day demonstrations of 2012, during which vandals smashed windows and disrupted traffic as police looked on. Judging by a report written later by a retired L.A. deputy chief named Michael Hillman, that seemed to happen largely because of the tension between Sanford, who was in charge of planning the police response, and Kessler, the incident commander. Part of the problem was that the two men confused officers with contradictory orders. In the aftermath, Kessler wrote his own scathing report, never disclosed to the public, which reportedly pointed fingers at Sanford.

According to the insider who talked about score-settling, the sentiment inside the department after Sanford retired and Kessler became assistant chief was, “Well, I guess Joe won that one.”

Really, though, resentments toward all the commanders who were in power before Bailey took over had existed for many years. “Officers have been working under a cloud of criticism,” explains O’Neill, alluding to the DOJ investigation. Meanwhile, he says, “the command staff seems to have gotten a pass.”

There was also a feeling that the commanders had lost touch with the rank-and-file, according to O’Neill. Bailey, in contrast, said at the meeting last week with guild members that commanders from now on would be required to spend one day a week at the precincts, working alongside officers.

“Your leaders have failed you,” O’Neill says Bailey told the crowd. The interim chief got no argument from the crowd.

nshapiro@seattleweekly.com