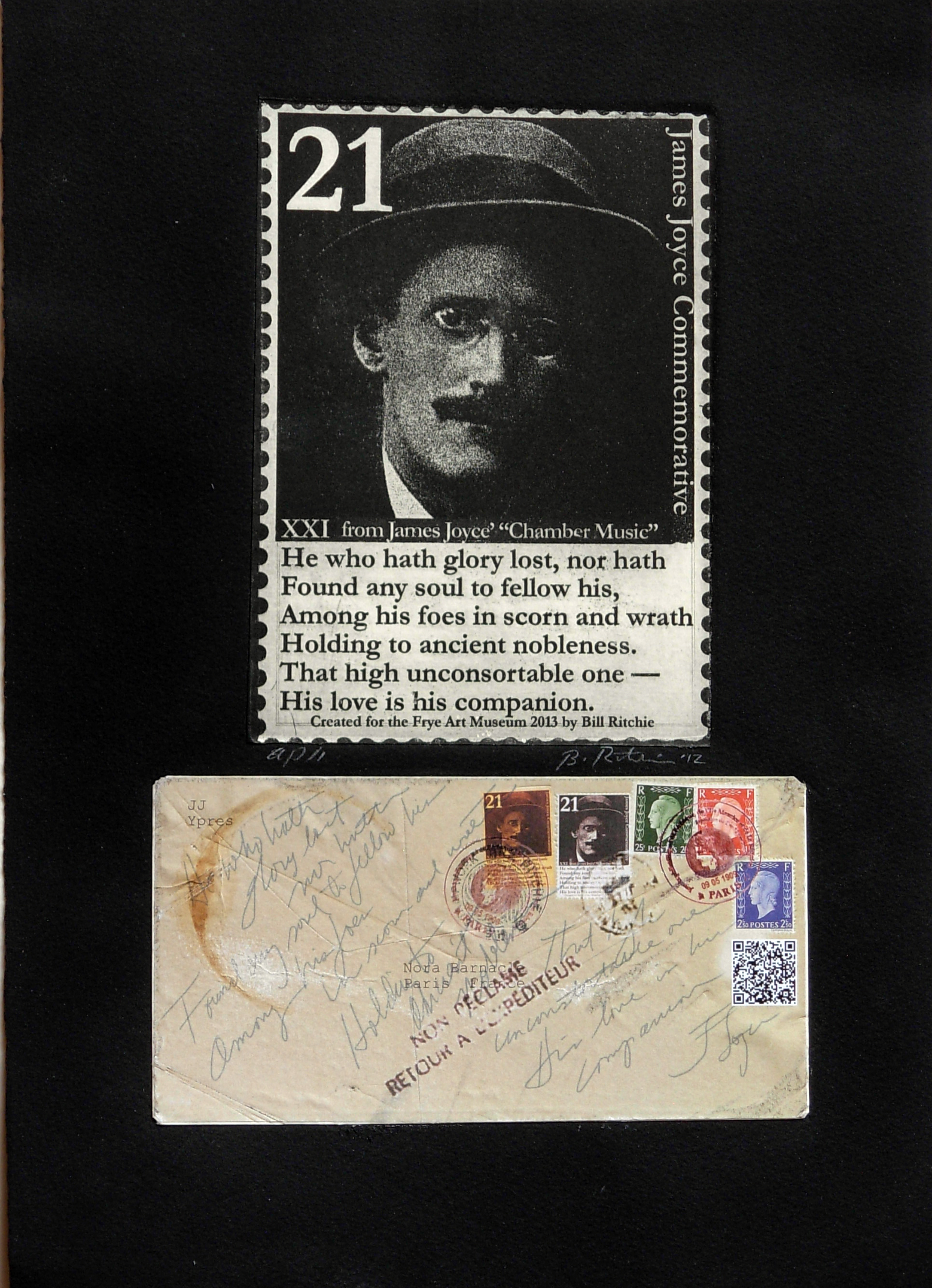

Apart from children’s exhibits, there’s usually a prohibition against touching anything at a museum. And to take anything would be a crime. Yet both the exception and the rule are part of the Frye’s two ongoing shows. The more novel one, commissioned by new curator Scott Lawrimore, is called Chamber Music, a companion to 36 Chambers, which excerpts the Frye’s permanent collection.

“Most people don’t know the Frye does contemporary art,” says Lawrimore as we walk through his show. The day after starting at the Frye last October, he explains, he began inviting local artists to create new works indirectly inspired by an old source: Chamber Music, a 1907 collection of love poems by James Joyce. That text inspired the show’s soundtrack, a 2008 anthology album, also called Chamber Music, softly playing on constant loop, with 36 musicians including Kinski, Mike Watt, Lee Ranaldo, and Peter Buck. (A video screen helps you keep track of the songs and their Joycean inspirations; the total album length is about two hours.) And, levels upon levels, text within text, it’s the music that Lawrimore sent out to prod his artists, one song each—though it’s hard to believe these curious creatives didn’t also read the source poems.

The 36 new works, mostly paintings, are hung numerically in the order of Joyce’s verses (and the album). You could, if obsessive, revolve clockwise around the room in sync to the music, but that’s not Lawrimore’s agenda. Instead, he wants visitors to sit and linger around the large, low three-armed wooden bench in the center of the room. In circular form, it’s modeled on a “gossip chair” (such as you’ll see in 36 Chambers in the adjacent gallery), but with a larger, more interactive intent.

Contained within the structure, a kind of artist’s supply cabinet, are three dozen cubbyholes in which each contributor has left a little trove of documentary materials. Go ahead and touch them, Lawrimore tells me; take them out and browse. For instance, Margie Livingston intends for you to handle the supple, rubbery sections from one of her congealed paint panels. They have a pleasingly tactile aspect, a texture you can only view on her wall-mounted work (No. 29 in the series).

On his shelf, Joey Veltkamp leaves books for you to study. On hers, Claire Cowie offers her own personal sketchbooks for you to examine, which include letters of encouragement from her father. And in the department of take-what-you-like, Alan Maskin leaves little handmade gifts that you’re free to remove. (Yes, the Frye’s museum guards have been notified, so they won’t tackle you on the way out; but return the other stuff after you’ve examined it.)

It’s a rare, interactive opportunity to sit and study in a museum; the gallery becomes like a library reading room. Or an archive, as Lawrimore also intends. His goal is “to start conversations about what the museum is going to be,” which includes documenting the city’s contemporary-art scene, today a half-century old.

A history-minded former gallery owner now associated with a 60-year-old museum (Seattle’s newest), Lawrimore has lately been reflecting back on those who preceded him, “these hidden histories of those who made a difference, these people who started galleries in their homes.” With what he calls “archive fever” running through his brain, he cites figures like Zoe Dusanne, Otto Seligman, and Linda Farris. Implicit in that shuttered roster are also recent casualties like Howard House, Western Bridge, and his own Lawrimore Project . . . all the galleries come and gone, now vacant storefronts in Pioneer Square and points south. If galleries are disappearing, Lawrimore muses, then maybe museums should help commemorate them along with the artists they represented. “People are contacting us with stories,” he says.

Still, the Frye has its older holdings to show. 36 Chambers continues the Joycean theme with poetry-inspired picks by the Frye’s staff—essentially everyone but Lawrimore, he notes with a laugh. “I didn’t want to assert any kind of aesthetic decree.” He just gave the Joyce verses to the non-curatorial team, the non-experts, and they made their picks. Oddly, there are only 26 paintings in response to 36 poems (some selected the same canvasses), but museums aren’t about math. E

bmiller@seattleweekly.com

Frye Art Museum 704 Terry Ave., 622-9250, frye museum.org. Free. 11 a.m.–7 p.m. Thurs., 11 a.m.–5 p.m. Tues.–Sun. Ends May 5.