If the two Seattle police officers who killed killed Che Taylor stay with the stories they related to internal investigators hours after the controversial North Seattle shooting in February, an inquest jury scheduled to review the case next week is likely to hear an unusual story of police self-defense: The officers, fearing for their lives, fired at Taylor from point-blank range after not seeing a gun in his hand.

They nonetheless assumed he was about to shoot them.

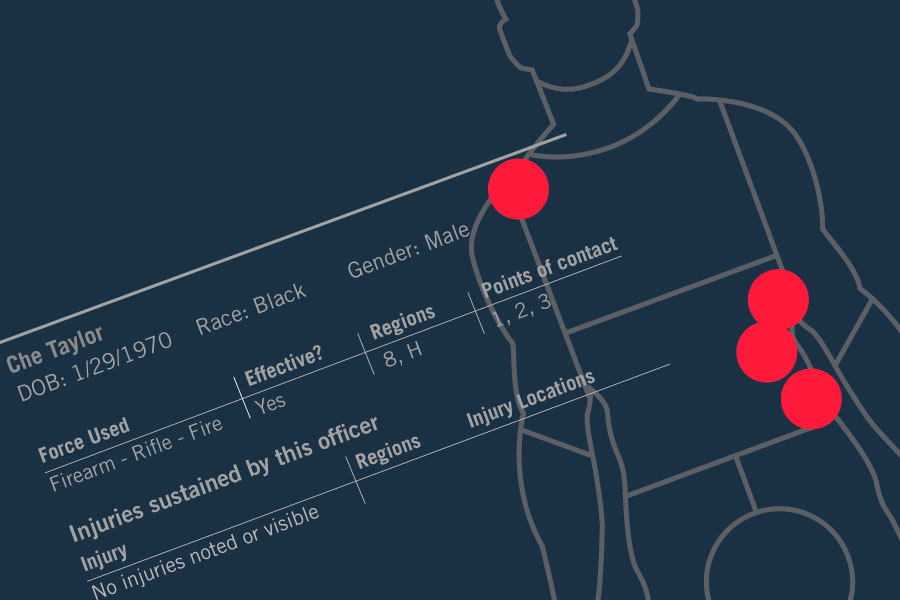

“We identified ourselves and I, and I told him, I called him by name, like Che T, let me see your hands, get down on the ground now, get down on the ground, two or three times and he said ‘Hey, what, what, what’s going on, what’s going on?’ ” recalled Officer Michael Spaulding in his late-night recorded statement before a department Force Investigation Team. He and fellow plainclothes officer Scott Miller, both white, attempted to arrest Taylor, an African-American, as a felon illegally carrying a weapon. They ended up opening fire in self defense, they said, hitting him four times (out of seven shots) in a nine-second curbside confrontation on Northeast 85th Street late that Sunday afternoon, Feb. 21. The 47-year-old alleged drug dealer was found to be carrying small quantities of heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine.

“At the same time, uh, Scott Miller’s saying the exact same thing,” Spaulding continued, according to 115 pages of transcripts of post-shooting interviews obtained by Seattle Weekly, detailing the officers’ lengthy versions of what happened moments before and after Taylor’s death. “While we’re talking to him, he’s facing us so we’re squared up to each other, um, and ordering him to get on the ground. He’s like ‘okay, okay.’ And while he’s doing that, instead of just getting down on the ground, which would be the easiest way for him to do that, is, because there’s, uh, the roadway right there, he could have just simply dropped down to his knees and went straight forward, but instead he turned to his right, um, to where his gun side was more towards the [car’s] side door that was open, and we were, lost sight of his right hip and his right hand.”

But did Taylor have a gun on him when killed? Miller had told Spaulding earlier that he saw Taylor wearing a gun and holster strapped to his right side when he’d emerged from his vehicle in the Maple Leaf/Wedgwood neighborhood. The two officers, members of a North Precinct anti-crime unit, were in the area to serve an arrest warrant on a suspected drug dealer when Taylor happened to drive up. The cops knew him by sight and by his criminal record, they said, and were aware it was illegal for him to be armed.

They called for backup by other members of their anti-crime team. Then the action began to go a bit sideways: According to police documents, the rest of the specially trained plainclothes team was busy elsewhere. Spaulding and Miller would have to make their move backed up by uniformed officers in marked cars.

After two patrol units took up perimeter positions, Taylor came around the block as a passenger in another vehicle that parked near the plainclothes unit. Taylor—about 6´4˝, 225 pounds—got out and stood on the curb, and police moved in. Armed with an M-4 assault-style rifle and a Winchester 12-gauge shotgun and sporting “Police” vests over their plainclothes, Miller and Spaulding crossed the street as the marked units pulled up with lights flashing.

“We told him to get down on the ground and he, uh, his right arm dropped down and while he, while his right arm dropped down, he started slouching over into the car and I saw his hand, right hand, go to his waist and then his elbow come up,” Spaulding recalled. “And I knew right there that he was drawing for the handgun. I didn’t see the handgun, but just that motion of it, I knew the gun was on his right hip, his hand went right to his right hip. I could tell, uh, that something stopped his hand from going down any further. And then he pulled—I could see his elbow going straight up to where he was un-holstering something. At that time I knew he was armed, knew the gun was on his right hip from what officer Miller saw. Uh, with the—at that time I was afraid for my life, Scott’s life, and everybody else’s life ’cause I didn’t think that he was willing to go to prison and—for that. So I started shooting.”

Spaulding fired six shots, Miller one. Taylor was hit once in the shoulder and three times in the upper torso. He showed signs of life afterward, but died at Harborview Medical Center.

Taylor’s death generated an uproar and rumors that police had killed yet another unarmed black man. Even after police insisted Taylor was armed, Seattle Black Lives Matter activists marched in protest and Seattle-King County NAACP President Gerald Hankerson called Taylor’s death “cold-blooded murder.” The shooting took place, as well, amid an ongoing nationwide debate over use of deadly force against African-American males and while the SPD is attempting to repair its reputation, under federally mandated reforms, as a department known for use of excessive force.

Taylor’s family claimed the gun found near his body, a Springfield Armory XDS .45-caliber pistol, was planted. It was originally purchased by a King County deputy sheriff, a federal official told The Seattle Times, but had changed hands at least twice thereafter. The family is seeking a Justice Department probe of the shooting, and claims the SPD tried to justify the death by quickly releasing details of Taylor’s violent criminal past, which includes rape, assault, and robbery.

The family’s challenge has not evoked much response from the feds, or sympathy from Seattleites, which is par for most officer-involved shootings: If police killed him, he must have deserved it (though that attitude is diminishing these days). The family hoped to raise $50,000 to pay legal fees. Six months later, they’ve received considerable vocal support, but just $3,877 in contributions.

“They said he didn’t obey their commands!” said Taylor’s brother, Andre Taylor, in a Facebook post. “Shit how could he when you just came up to him and started shooting!”

A dash-cam video from one of the arriving marked police cars, released publicly by the department, conflicts somewhat with the officers’ statements. It shows Miller and Spaulding closing in on Taylor, leveling their long guns at the suspect, then shooting him. A uniformed officer is also in the street, handgun leveled. It all unfolds with mind-boggling speed—the takedown lasts just under nine seconds, from the moment “Move in” is heard until shots are fired. No commands are heard from the vid in the first five seconds; then Taylor, with the officers pointing weapons from five feet away, seems startled, starts to raise his hands, and is told to “Get down, get on the ground.” In the last three seconds, when he was reported “staring” and not responding, as the officers claimed, he immediately bends at the knees to go down in the small space between the door and car as the two officers move closer, shouting “Hands up, right now, hands up.” Spaulding is inches away, reaching down toward Taylor; the video stops and the shots are heard. (Though there is more to the video, police opted, as they usually do, not to release the death scene).

Miller’s version differed slightly from Spaulding in a separate interview with internal investigators that night. Like Spaulding, he gave a lengthy analysis of his thoughts and reactions that flashed past within those few maddening seconds. “I do not recall him responding in any affirmative way,” Miller said, recalling Taylor’s behavior. “I recall him standing, giving us the, quote, unquote, thousand yard stare and as we moved, as we kind of began to move to get a better angle on him um he, his response was like I said, to maybe to physically start to crouch into the passenger side of the vehicle, turn his body slightly toward us, which was to us a threatening move, because he might be trying to get a better stance in which he could turn, draw his weapon and it appeared as though he did draw his weapon which was then confirmed when we saw the weapon in the car later on.”

Miller also said—in contrast to the video showing Taylor immediately attempting to raise his hands and then bending, or going to, his knees, “Again, while all this is going on, both Spaulding and I are both saying, ‘Che T, show me your hands,’ and we’re also saying ‘get on the ground, show us your hands, get on the ground.’ Again he does not—he is not moving, and this is happening pretty quickly but he’s not showing any signs of complying with what we’re asking him to do. We move around to the back of his car, we start to, to approach him to close the, close the distance, we need to, we need to make sure we have the advantage of action over having to react to him.”

Neither officer ever saw a gun in Taylor’s hand, they said. But after he was killed, they said, they found the .45 partially concealed under the front passenger seat next to where Taylor fell. A fire-department medic said that to treat Taylor’s wounds afterward, he had to cut off the dying man’s belt, to which an empty holster was attached.

The officers made no comments about the possibility that if Taylor was drawing a gun, perhaps his intent was only to ditch it. That could help explain how the gun got under the seat so far. If he merely dropped it, the weapon was more likely to land on the floorboard.

During their post-shooting interviews, the officers were not clear about how the .45 got under the seat, hidden except for the butt of the gun. Both officers said they felt Taylor was going for the weapon in his holster, suggesting it fell from his hand after he was shot and slumped into the doorwell.

“When his hand reached for his hip,” Spaulding told investigators, “there was no question in my mind that I thought that he was going for that gun. There was, there was no reason for him to turn, to, to hide the right side of his hand and the right side of his hip out of our sight, to reach down, put his hand out of sight when he, when we’re ordering him to the ground. And then also as soon as he grabbed onto whatever he was reaching for on his hip, he pulled it straight up like you would a gun out of a holster. So I just, I believed he was going for his gun.”

There were two close-up witnesses to the shooting: a 59-year-old white man behind the wheel of the car Taylor had stepped from and a 32-year-old white female passenger in the back seat. Besides the shooting video, police released an in-car vid of the woman sitting in a patrol vehicle that day, talking about Taylor apparently going for a gun.

“So I’m assuming that guy died then, right?” she asks an officer, who answers that he doesn’t really know. “They we’re just like, you know, ‘Get on the ground’ … and I think he pulled out a gun, and then he shot back I think, and then he died, I think, that’s what happened.” Like the officers, however, she was in no position to see whether Taylor actually pulled out a gun, and officers did not say he fired a weapon.

In a later interview with Seattle blogger Charlette LeFevre, the woman said Taylor had no gun. “I thought they would give him a second or two to put his hands up—it didn’t happen,” she said, adding that she did not see Taylor with a gun in the car. Asked if he saw Taylor with a gun that day, the man who’d been in the driver’s seat, with the best view of events, told LeFevre, “I did not, no.”

Asked by an investigator if he and Spaulding had planned to take Taylor into custody alive, Miller answered: “Oh we would, if he had complied with what we had asked him to do, which was get on the ground. Then Officer Spaulding and I would have held on him with our, with our long guns uh, maintained a lethal cover of him because he was armed and the other uh arrest teams, the marked uniform patrol guys … they would actually come in, physically take him into custody. Like put handcuffs on him, secure him there while we held on him with lethal coverage.

“And that was pretty clear to me that’s, I think pretty, I thought it was pretty clear to everybody.”

Clear to everybody except Taylor, perhaps, who was indeed handcuffed, after he was shot.

Was it justified?That’s what an inquest jury will decide at a hearing set to begin next Monday, September 19, in King County District Court. Jurors, who are likely to hear questioning about overreactions and lack of planning (what about the threat presented by the two other unknowns in the car, and where was a supervisor to oversee the high-risk takedown?), will vote up or down on whether the use of deadly force was necessary. King County Prosecutor Dan Satterberg will then use the outcome to help decide whether any charges should be filed against the officers.

They almost never are. A 2015 Seattle Times report, “Shielded by the Law,” found that Washington has the most restrictive law in the U.S. regarding police use of deadly force, requiring a prosecutor to prove an officer acted with malice. Andre Taylor, Che’s brother, is currently helping lead an initiative effort to reform state law to make it easier to prosecute police. Called the John T. Williams bill, I-873 is named for the native woodcarver killed almost instantly when he was seen with a knife by Seattle cop Ian Birk in 2011. Birk couldn’t be charged in the death, but did resign.

Most officers use the feared-for-my-life defense and, with the suspect dead, do not have to worry about contradiction. In one of the most controversial recent cases, captured on a viral video last year in Pasco, police chased and wounded, then killed, a rock-throwing Latino suspect, 35-year-old Antonio Zambrano-Montes, in a barrage of bullets. He is shown in the video holding out his empty hands in what his family’s attorney says is surrender. But neither the county or U.S. prosecutors felt the officers should be charged. Last week, state Attorney General Bob Ferguson joined the chorus, saying the point-blank shooting of the unarmed farm worker “did not exceed the legal standards for the justifiable use of deadly force.”

Of 213 police killings statewide from 2005 through 2014, there is only one instance of an officer actually charged in a fatal shooting. He was found not guilty.