Inspired in part by the hunger strikes over the years at the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, a privately-run detention facility for undocumented immigrants, U.S. Reps. Adam Smith and Pramila Jayapal announced Tuesday a piece of federal legislation that could, theoretically, do away with the NWDC altogether.

The Dignity for Detained Immigrants Act of 2017, co-sponsored by Smith, Jayapal, and 39 other members of the House so far, would first establish enforceable federal standards for such facilities across the country, including requirements that detainees be fed adequately, offered adequate medical care, and have recourse if they have complaints about their living conditions. (These are issues that NWDC detainees often brought up when on hunger strike).

The act would also repeal mandatory detention for immigrants, requiring probable cause for keeping an undocumented person—rarely a convicted criminal—in jail or detention while they’re undergoing civil proceedings. Currently, immigrants can be held for weeks, months, or even years while waiting on a brief hearing from a judge. And it would, ultimately, phase out the use of privately-run immigration detention centers entirely.

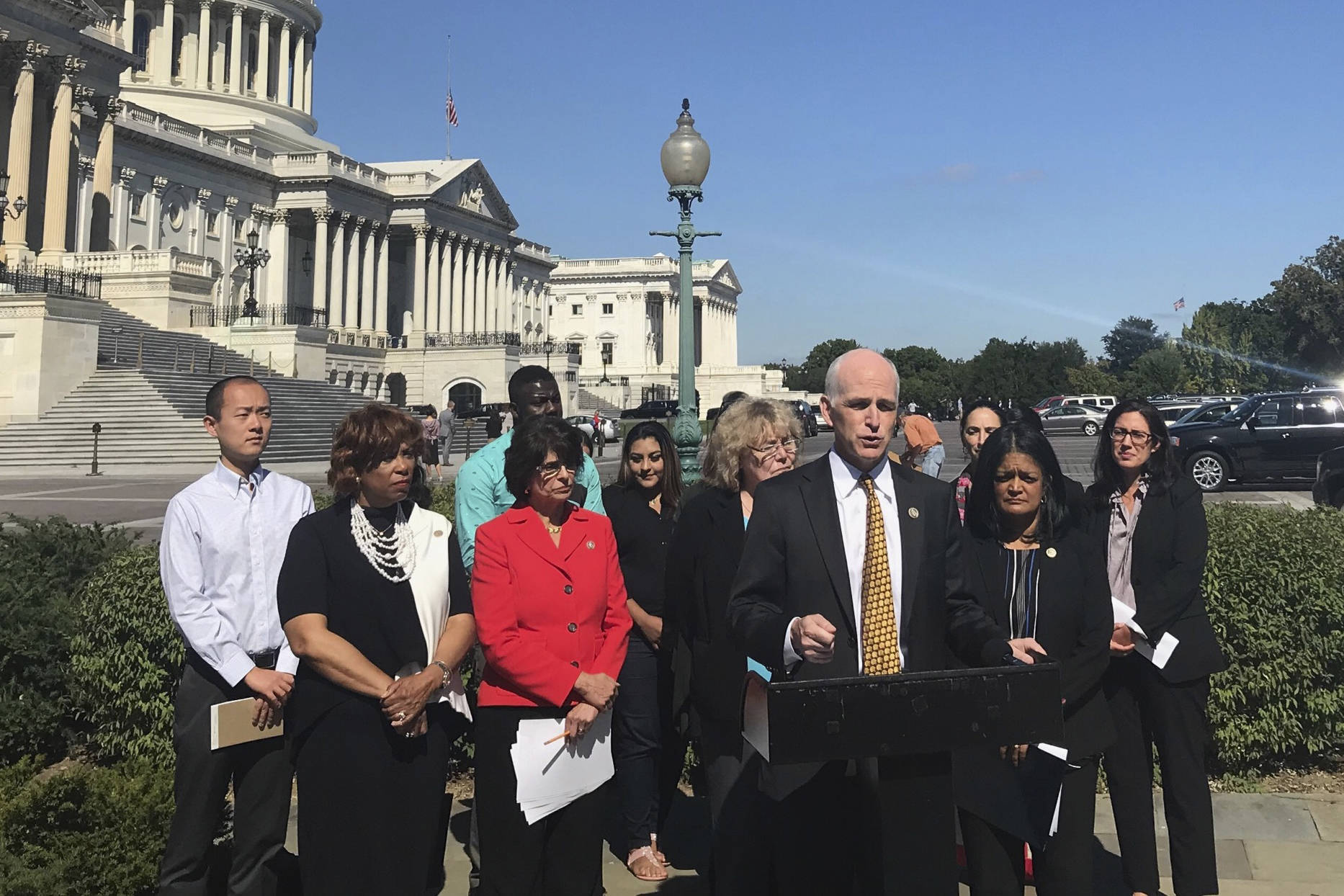

The immigration detention system, as it stands, “is just wrong,” said Jayapal at a press conference in Washington, D.C., on Tuesday, flanked by representatives from a handful of national advocacy organizations including the ACLU and the National Immigration Justice Center. “It is morally wrong, and it is economically wrong.” Approximately 38,000 men, women and children are detained every day, she said, costing taxpayers $2 billion a day, which could jump to $3.2 billion if Congress authorizes an increase in the detention bed quota. “Our broken immigration system, let’s be clear,” she said, “is a profit-making enterprise of large, private corporations.”

One goal of the proposed legislation, Smith explained, is simply to set standards for how people are treated in private facilities right now. “The detention facility like the one in my district, in the Tacoma tideflats, does not have any federally mandated regulation on how the detainees are to be treated, in terms of food, in terms of work schedule, in terms of when they can be put into isolation,” he said. All of that, he said, is up to the discretion of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

In 2011, ICE did revise its detention standards in order to “improve medical and mental health services” and “improve the process for reporting and responding to complaints,” among other things. Smith and other speakers on Tuesday emphasized a lack of transparency and accountability to such standards, however. U.S. Rep. Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-Calif.) told a story of a visit to a facility in Texas where an infant’s back was covered in sores, but her mother was told the child should just “drink water.” Part of the bill would require unannounced inspections of these facilities.

Humane living conditions, then, are paramount. But the next big goal of the bill, Smith said, is to get rid of private prisons, period. “We think all privately-run detention and prison facilities should be eliminated because the for-profit motive is part of the problem,” he said. “Part of the reason the food is so awful is because [the companies] are trying to save money. Part of the reason they don’t pay detainees what they should pay them for the work that they have them do is, again, because they are trying to save money.” (Last month, Attorney General Bob Ferguson sued GEO Group, the second-largest private prison company in the nation and the operator of the NWDC, for paying detainees $1 a day and thus violating Washington state minimum wage laws.)

Smith, in his statement, also pointed to the fact that in August 2016, the Obama Administration announced its plans to gradually phase out the use of privately-run federal prisons. In February, the Trump Administration reversed that order. The Obama Administration order, however, focused on federal prisons contracted out by the Bureau of Prisons, not immigration detention centers contracted out by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and ICE. In December 2016, a special report by a subcommittee of the Homeland Security Advisory Council (HSAC) found that, for fiscal and capacity reasons, private companies should continue to run immigration detention centers. Still, of the 23 members of the HSAC, 17 disagreed with that recommendation, concurring that “a measured but deliberate shift away from the private prison model is warranted.”

“GEO has a long history of providing culturally responsive services in safe and humane environments … as confirmed in the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Advisory Council report in 2016 on privately operated ICE facilities,” according to a statement provided by GEO Group. “As a matter of long-standing policy, GEO does not take a position on or advocate for or against any immigration policies—such as the basis for an individual’s detention or the length of detention—but we welcome the opportunity to meet with lawmakers and other stakeholders to dispel the myths about our company and discuss how we partner with the federal government to provide high-quality services and advance best practices.”

If enacted as written, the Dignity for Detained Immigrants Act would, from the day of its enactment, prohibit the Department of Homeland Security from entering into or extending any contract with a private prison company. DHS would also be required to terminate any such contract it had within three years of the law’s passage. NWDC renewed GEO Group’s contract in 2015 through 2025. If this act passes, therefore, and if the NWDC still exists three years afterward, at that point the NWDC will be owned and operated by DHS, not GEO Group.

Daniel, a Chicago-based medical student from Nigeria who spoke on Tuesday, said he won his asylum case in August, which was a relief; but there was no reason he should have been detained for five months, with limited communication with his family and attorneys, inadequate food, and dangerously inadequate medical care while that civil proceeding was ongoing. “I spent my days doing nothing but crying,” he said. “I never imagined in my life I’d be in a jail facility. All my life, I’ve never even been to a police station.” He became critically ill while in detention, he said, and, he, too, was offered water instead of medical treatment. “I asked to see a physician but I was denied. The response to me was I should drink more water,” he said.

It is time, Jayapal said, “to overhaul the system” and create alternatives to this kind of detention. “How do we restore the authority of oversight, transparency, and accountability to the Department of Homeland Security again, instead of to private prisons who benefit from this? [We need] to think of this system as it was intended to be: A civil system intended to hold people for short periods of time. That is no longer what it is.”

The proposed legislation “gives me hope,” Daniel said, “that this government can find a way to stop the inhumane treatment” of people in detention. “I ask that our country and our country’s leaders remember that all human beings have rights and deserve to be treated with dignity, regardless of what the cost might be.”

sbernard@seattleweekly.com

This post has been updated to clarify the Obama Administration’s order to phase out privately-run federal prisons and to include a statement from GEO Group.