Seattle’s city-sponsored homeless camps are working even better than expected.

That’s the short version of a report just released by the Seattle Human Services Department reviewing the first year and a half of camps in Ballard, Interbay and Othello. The camps—comprised of tiny houses and/or tents on platforms—are administered by the homeless advocacy and services groups SHARE and Nickelsville. Based on data from the federal Homeless Information Management System (HMIS) from September 2015 through May 2016, the report says that 759 people have lived in the camps and 121 of them found a “safe, permanent place to live.”

“The City-permitted encampments have met and exceeded the contracted performance measures,” it reads. “The model is successfully serving people who have been living outside in greenbelts, on the streets, in cars and in hazardous situations.” In addition, the report says, crime hasn’t spiked near encampments, and neighbors have warmed to them over time.

Part of the reason the camps are so successful is they aren’t constantly moving from one site to the next. “In the past encampments, or tent cities, were only permitted to stay in one location for a 90-day period,” reads the report. “The disruptive nature of the 90-day limit placed a burden on the encampment community.”

One more benefit: increased community, in the form of human infrastructure that grows into place around the nexus of a camp. Multiple people testified during public comment about how much the Interbay camp has become a part of their community, and at the same time stimulated community building among housed neighbors as they came together to support the camp. “The churches didn’t really talk to each other before this,” said Magnolia Community Council trustee Janis Traven, “but now there’s a reason to talk.”

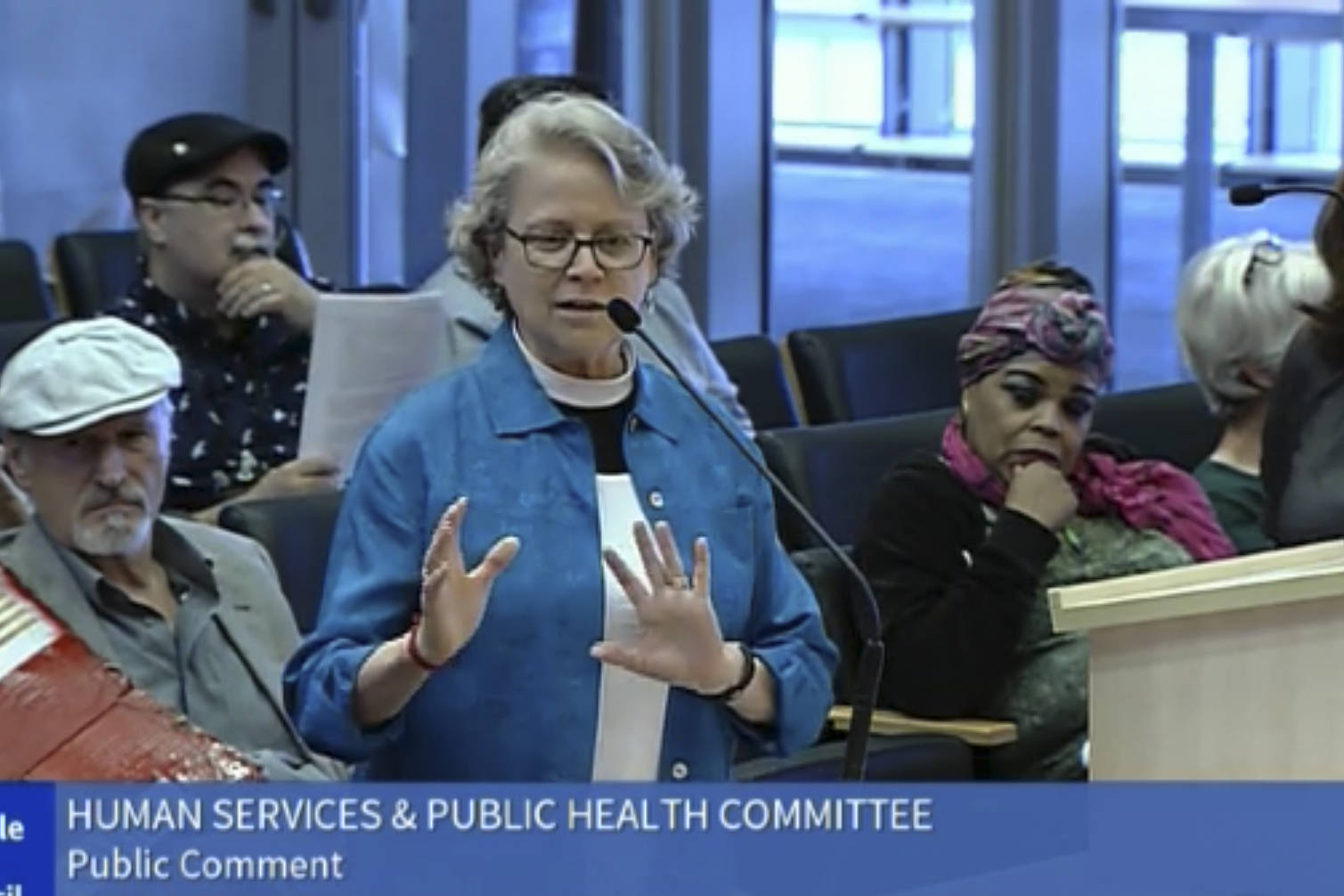

The Rev. Marilyn Cornwell, rector as the Episcopal Church of the Ascension in Magnolia, said that hosting Tent City 5 in her neighborhood “has been fabulous.” Neighbor representatives meet with camp representatives monthly, she said. “Over the course of the [almost] two years, things have changed dramatically from that fear-based outcry of ‘Not in my backyard’ and ‘Bad things are going to happen,’ to, ‘Oh, these are our neighbors,’” said Cornwell. “They help clean up the neighborhood…[and] they have a good relationship with the Seattle Police Department.”

Traven said that “the experience has been great. It also has been eye-opening…The city did some public scoping meetings that were fairly wild and crazy. There was a lot of venom. A lot of people conflate homeless people with crime and threat…It delayed the encampment from going in for a while.”

Traven wants the camp to stay in Magnolia. “I think it’s crazy that there should be an arbitrary time limit for how long they can stay. There’s been human capital invested,” she said. Councilmember Sally Bagshaw said during the Seattle City Council’s Human Services and Public Health committee meeting on Wednesday that she will work to help Magnolians keep Tent City 5.

The camps aren’t perfect. According to the report, communication and unclear roles are still significant problems. So are racial disparities. Relative to the overall population, whites in King County are underepresented among the homeless population but overrepresented in authorized encampment population; vice-versa for black and Native people. Decreasing that racial gap will be a priority going forward, the report says.

cjaywork@seattleweekly.com

This post has been edited.