THEY TOLD YOU about being careful what you wish for, and the Seattle Monorail Project is here to demonstrate why. The $1.75 billion elevated transit line remains a blurry outline in the distance a year after its unenthusiastic voter approval, and it’s hard to tell which direction it’s going. Barely on the drawing board, the people’s train is already pulling a load of miscalculation and miscommunication that threatens the monorail plan and is forcing officials to jettison some of the weight. That includes the possible loss or shrinking of proposed stations, changing some double-rail track to a less costly but slower single-rail system, and cutting corners on everything from escalators to hand rails to make up for an astonishing shortfall currently estimated at one-third to nearly one-half of the projected tax revenue.

Amid the uncertainty, it’s clear the monorail will not be the innovative rapid transit system that voters underwhelmingly approved by a margin of 877 out of the 189,000 ballots cast last November. The start-up 14-mile line is being financed from a shaky single sourcea new tax added to vehicle license tabs bought by Seattle residentsand the expected initial revenue of more than $4 million a month has so far been short by almost $2 million. The vehicle valuations on which the monorail based its revenue projections were wildly off markan error of $1 billion or more. Officials hope to recover by cutting costs and taxing the license tabs on some currently exempt vehicles, which might require legislative action and invite legal challenges. The monorail is banking as well on tracking down the supposedly thousands of Seattle scofflaws who might be registering vehicles at addresses outside the city. The Seattle Popular Monorail Authority claims it is losing more than $3 million annually to slackers, but that estimate, too, is based on questionable data. “There is evasion to some degree, some anecdotal evidence of it,” says Brad Benfield, spokesperson for the state Department of Licensing, which collects the motor-vehicle excise tax being used to design, build, operate, and maintain the monoraila development process known by the unfortunate acronym DBOM. “But we just don’t have any figures. I don’t know where they got theirs.”

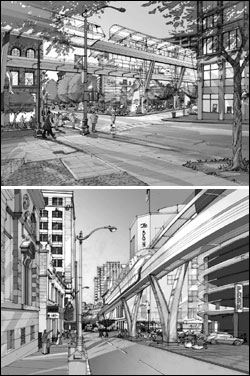

All this foreshadows the monorail’s other looming challenges: design and right-of-way acquisition. The monorail project is building the equivalent of a one-lane freeway through downtown Seattle. The revenue shortfall, when combined with inevitable lawsuits and construction overruns, threatens to turn the budding monorail into another R.H. Thomson Expressway the planned freeway through east Seattle that was halted in the 1960s by citizen opposition, and which today consists of a freeway ramp to nowhere near the Arboretum. Says monorail critic Geof Logan: “What we may wind up with is not a monorail, but a bill for one.”

Has DBOM gone off in Joel Horn’s hands? If so, he doesn’t appear to notice it. In his signature upbeat fashion, the project’s executive director sees the loss of millions in possible revenue, which he and others initially covered up, as an opportunity rather than a failure. “There are two silver linings to this,” he says. “One is that we found out about it early, rather than a year or two from now when we would have had to start over.” He and others say this will force prudent decision making, which raises the question: What kind of decisions had the monorail authority been planning to make? The other plus, Horn says, is that “this is forcing us to think out of the box, how to do innovative designsyou know, less expensively.” Will it be anything like the monorail promised and pictured in 2002, sleek and ethereal on its delicate guideways, sliding in on time and on budget? Despite his otherwise sunny views, Horn was noncommittal. “We’ve said over and over, when you’re building the biggest public project in the history of Seattle, you just don’t know until the bids come in” next spring. That might have been the fine print on last year’s ballot, but Horn insists the monorail authority is being responsive to the public’s angst. “We’re tightening the belt on everything we do. You’ve seen our offices? No one has a private office. Even I’ve got three people in my office. . . . We have recycled furniture. We are doing everything we can to keep the price down.”

DOUBLE BUNKING might be more a public relations move than a financial strategy for a project that is burning through more than a million dollars a week. Its $86 million first-year budget is being shored up by a $70 million extendable line of credit. An initial $750 million bond sale was delayed until next year. (Thanks in part to stern advice from state Treasurer Michael Murphy, the monorail board opted to abort the bond offer just months before it discovered the shortfall, which would have imperiled the sale.) Besides some hefty staff salariesstarting with Horn’s $172,000, about $35,000 more than Mayor Greg Nickels is paidthe monorailers just spent $52,000 on a consultant to investigate how they screwed up the tax projections. They measured once and cut twice, or, in the words of state licensing spokesperson Benfield, “They weren’t, like, sending things back for us to check before the electionthe monorail projected its figures before our agency even had contact with them.”

The project also just spent $20,000 on a survey to find out how people feel about their efforts so far. (The survey found “tremendous, widespread” support, says a breathless monorail press release.) The 600-person sampling was taken despite nearly 10,000 public comments, letters, and e-mails already logged at monorail headquarters on Fourth Avenue. Horn nonetheless finds the new research persuasive. “There is a very strong supermajority of people who are against every capital project,” he notes. “But in the survey, only 4 percent said we were moving too fast.” Many of last year’s “no” voters (the cliff-hanging approval rate was 50.23 percent) are supporting the monorail now, Horn thinks. “Some of them come to our meetings and say, ‘I voted against it, but now that it’s approved, I want to do everything possible to get it built.'”

BUT OTHERS COME to the meetings and say the opposite. At a recent forum, an elderly, white-haired woman named Belle Silver, a resident of the Central District, got hold of a microphone and waxed fondly on old Seattle and its erstwhile street cars and cable cars. But she doesn’t like this new elevated contraption that will block views, sit on big ol’ poles, and plow through pretty neighborhoods and historic buildings. She thought the public was misled about the project’s financial and construction impact. “Have another vote on it, with the facts,” she told Horn, who was sitting nearby, smiling until she mentioned a revote. And after the measure is defeated, she added, “use the money to provide free buses.”

Others followed her to the podium to also plug a rubber-tire rapid trolley system and warn that if you think Seattle’s got congestion now, wait till you see it during the next 1,800 daysa “citywide Mercer Mess,” as one put it, created by a five-year construction marathon that includes the building of Sound Transit’s new lines and a solution for the Alaskan Way Viaduct. Tom Linde of West Seattle thought that Horn and his monorailers were “Coug-ing it,” referring to his wife’s alma mater, Washington State University; legend has it the Cougars choke under pressure. But he brought the smile back to Horn’s face when he added that, while monorail officials may have to hold their noses and make some choices, “this project is doable.”

HORN IS BOTH HEALER and divider in the ongoing planning. His supporters are infected by his optimism, while his critics can barely hold their spittle. One describes his monorail directorship as “performance art” but adds, grudgingly, “He’s someone you’d want to be in a foxhole withhe’s good under fire.” A late-career political operative with no experience as a mass-transit guru, Horn made a rookie error by hiding details of the potentially catastrophic shortfall (he says the initial numbers were not clearly indicative of a crisis). Some felt he and board Chair Tom Weeks should have been fired for not immediately informing the board, which theatrically shook its finger and moved on.

A serial backroom deal maker, Horn was the force behind the twice-failed Commons park/real-estate development, as well as the giveaway of PacMed hospital to developer Wright Runstad and Amazon.com. So is this an opportunity for Seattle or for Joel Horn? “I think that’s a very, very typical kind of conspiracy theory that people have. It’s a natural thing to suspect, I guess,” he says. “But what we do is so public, it’s all there for people to see.” Well, maybe not all, as a number of critics, whose public records requests have been rejected by the monorail authority, might point out. Still, the monorail planners invite criticism. “We encourage it; it keeps us on our toes,” says Horn. He is not surprised, in light of the narrow election, that opinions on building the monorail would also be evenly separated into pro and con campsor, for illustration, into separate Joel camps: the Joel Horns and the Joel Pastons.

Paston, a mild-mannered Seattle software consultant who got interested in the project partly because he felt the license-tab tax was based on inflated vehicle values, has become a sought-out critic of the project and a regular figure at board meetings. He’s a reluctant public persona and is often asked to “please speak up, Mr. Paston” when he takes to the microphone. But though he says press interviews “creep me out,” he’s too ticked off to stay silent and hopes others follow his lead. “After I went to a couple meetings, I got sort of sucked into it all,” he says. “When I asked questions about the valuations, I just got blown off or told ‘I’ll get back to you on that,’ and of course they didn’t. It kind of infuriated me.” He has now started a Web site (www.monorailtax.org) that includes a tax estimator, budget studies, and an ever-growing list of challenges for the other Joel to solve. “The [monorail] staff found out about their revenue shortfall in early April,” writes Paston, whose Web site in July was the first to publicly sound the shortfall alarm. “And they covered it up. Even from some board members voting on major expenditures. That’s just unbelievable.” He sees the motor-vehicle excise tax, or MVET, as somewhat self- defeating. It’s “naive to think that the MVET itself will have no effect on vehicle purchases and ownership,” Paston notes. Echoing election complaints that the whole city will pay for a service limited to a comparatively few west-side neighborhoods (it is proposed to go citywide once most of us are dead), Paston envisions a rebellion against the elevateds and a new culture of monorail alternatives, such as a car lot called F.U. Monorail Motors that offers free loaners to the trainless. If it turns out there’s not enough revenue to do the project right, Paston says, “they should bring it back to the voters. Sure it might be turned down, but if they’re doing their jobs, they should be able to make a good case for more

funding.”

Could that happen? The other Joel rolls his eyes at the thought. “Let’s just wait for spring,” Horn says.