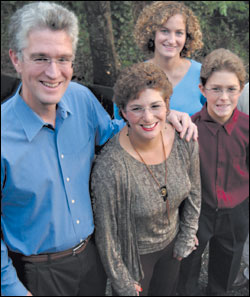

When Jim and Fawn Spady launched a crusade for charter schools in this state after becoming disillusioned with public ones, their son was in kindergarten, their daughter in second grade. Now, son Saul only has a couple more years left of high school, and daughter Jasmine is in college. It’s been that long. And still, despite the arduous efforts of the family that presides over Dick’s Drive-Ins, despite two initiatives and four charter bills in the Legislature, we don’t have a charter law.

So is there really any reason for the Seattle School Board to get all hot and bothered over yet another charter bill that the Legislature will consider this session? Last week, the newly radicalized board held a public hearing on charter schools and then passed a resolution opposing the new bill.

In fact, this might be the breakthrough year for charter schools, which are public schools run by private groups, operating independently of district bureaucracies to ensure maximum flexibility regarding curriculum, staffing, and budget. “I think it’s the best chance we’ve had,” says state Sen. Steve Johnson, an ardent charter proponent who chairs the Senate’s education committee. Democrats generally view charter schools skeptically, as a step on the Republican path to dismantling the public education system. But Johnson, a Covington Republican, notes that charters enjoy a measure of bipartisan support in the House as well as the blessing of Democratic Gov. Gary Locke and Superintendent of Public Instruction Terry Bergeson. Charters have less Democratic support in the Senate, which in the past has sealed the fate of charter bills. Republicans have since taken over the Senate, though, and the chamber narrowly passed a charter bill last year.

Charter supporters say the bill would have easily passed the House had it gotten to the floor. Instead, it was held up in the Democratic caucus, where it was presented two hours before the end of a grueling special session focused on the state’s all-out bid to entice Boeing to build the 7E7 here. As the reigning party in the House, the Democrats get to say what makes it to the floor for a vote. Last year, though some members of the caucus supported charters, not enough did to call for a vote.

THIS YEAR, WITHOUT a Boeing-caliber distraction, charter supporters think they can put their issue on the agenda early enough to get a House vote. It’s still an uncertain prospect, however. So Dave Quall, a Mount Vernon Democrat who chairs the House education committee and has for years been pushing charter bills, is busy negotiating a new one that he hopes will be more palatable to fellow Democrats. “We think maybe we can make some members of our caucus more agreeable,” he says.

For one thing, Quall says he’s thinking of limiting the number of charter schools to 25 over five years. Last year’s bill would have allowed for 70. That, in turn, was a far cry from the original charter-school initiative put forward by the Spadys in 1995, which had no limit. While that 1995 initiative had few restrictions on charter schools, Quall’s draft bill requires that groups running charters be nonreligious and nonprofit, that their teachers be state certified, and that they demonstrate sufficient liquid assets. Further, would-be charter operators must first seek permission from a local school board, which would be required to hold a public hearing before granting approval. If the school board said no, a putative charter group could appeal to the superintendent of public instruction and might have alternative recourse, depending on what Quall decides. Green-lighted charters would be evaluated at the end of five years according to the goals they’ve promised and could be closed if judged unsuccessful.

“This is a very modest proposal, a very toe-in-the-water type of proposal,” said Jim Spady at last week’s Seattle School Board hearing.

THERE’S ANOTHER big change from original charter proposals, aimed in part at enticing Democrats concerned with the plight of minorities and the poor: The focus is on “disadvantaged” kids. Last year’s proposal reserved priority for such kids among limited charter slots; this year, Quall says he is considering whether to stipulate that charters only be granted to schools serving disadvantaged kids. “That way, who could argue against it?” Quall asks.

Well, African-American activist Angela Touissant, for one. “I’m tired of folks trotting out disadvantaged children as a way to move their agenda,” she said at the School Board hearing. “I can’t see how taking money away from public schools is going to help disadvantaged kids.”

It is a common argument among charter opponents, including those on the Seattle School Board, that charter schools would siphon money from public schools. The argument is somewhat deceiving. After all, charters are public schools, open to all, without tuition. But districts might have to maintain all their existing schools while giving up per-pupil state expenditures for new charters. In that way, existing schools, serving the majority of students, might be harmed.

At the same time, points out Fawn Spady, there’s a lot of money floating around for charters that would likely be injected into the state’s public schools, should a law be passed. The federal government provides grants of hundreds of thousands of dollars to new charters. The Seattle-based Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has given

about $150 million so far to charter schools around the country, according to its education director, Tom Vander Ark. “I’m quite certain we’re the largest charter funder in the U.S.,” he says. What’s more, Vander Ark says that the foundation, frustrated by an inability to fund charters locally, is eager to put money into launching a network of charter schools in Washington state, should a law be passed.

SO IT’S ARGUABLE whether charters would be, financially, a boon or a bust to local public education. An even more puzzling question is what results charters would achieve. It’s been 10 years since the first charter law passed in this country. Since then, laws have been enacted in 40 states plus the District of Columbia.

“A record has emerged,” says Charles Hasse, head of the Washington Education Association, the state teachers union, which opposes charters. (Typically, charters are nonunion.) “Charters are not living up to their promise,” Hasse says. In contrast, the pro-charter Center for Education Reform, a nonprofit based in Washington, D.C., celebrates “a record of success” in a paper on the matter. Both sides bat about studies that purportedly prove their point.

Late last year, however, came more comprehensive evidence. In the book Taking Account of Charter Schools: What Happened and What’s Next, Western Michigan University researchers Gary Miron and Christopher Nelson published a review of neutral studies on student achievement at charter schools nationwide. The studies showed, essentially, that charter schools performed on average about the same as regular public schoolsin some states they did a little better than comparable public schools, in some states they did a little worse. That record deflates the lofty promises made by charter-school advocates, who present them as a startling innovation destined to turn around the dismal socioeconomic achievement gap that has made the public education system seem like a failure. If charters, in many cases, are struggling just to meet the standards of regular public schools, what’s the point?

And yet, the concept of charters has yet to be played out. Even the authors of that comprehensive review of studies, published last November, preface their findings with warnings about what early days these are for charters, how few reliable studies there are. Charter advocates concede that they have learned from mistakes.

Most importantly, despite the mediocre success of charter schools on the whole and some stunning failures of individual charters, there are enough exceptionally good charters out there to entertain a belief in their potential. The Gates Foundation went around the country looking for the best high schools, says Vander Ark. It found many of them were charters that maintained what Vander Ark calls a 50/50/80 standard: At least 50 percent of students were minority, at least 50 percent were poor, and at least 80 percent graduated from high school and went on to college. They include High Tech High in San Diego, which emphasizes math and science, and the Met in Providence, R.I., featuring unstructured project work.

AT THE MIDDLE-SCHOOL level is KIPP, a nonprofit group that runs numerous charter schools around the country that serve mostly poor African Americans and Latinos. One is the top-performing middle school in the Bronx. KIPP spokesperson Steve Mancini says his organization would like to open a school in Washington state.

Examples like that are what make charters hard to reject for leaders like James Kelly, president of Seattle’s Urban League. Charter schools are not a panacea, he stressed at the Seattle School Board meeting. But with more than 80 percent of black and brown children in the state failing the high-stakes Washington Assessment of Student Learning (WASL), Kelly said, “we must continue to offer options.”