The Seattle City Council last year passed an ordinance giving drivers for Lyft and Uber, and other for-hire drivers, the right to unionize. It was a big step forward for labor in an economy increasingly comprised of contractors who aren’t protected by traditional labor laws.

Monumental though the ordinance was, it was also somewhat vague on necessary details concerning how unionization should actually happen. With the city pushing to put the law into effect this fall, the biggest question remains: When Seattle drivers vote on whether to form a union, who gets to vote? And if a union is created, who gets a say in the contracts that are negotiated?

At the end of last year, Seattle became the first city in the country to pass an ordinance setting up a way for ride-share drivers to organize for better pay and working conditions. But when the City Council unanimously passed the legislation, they punted critical questions about who gets to vote in that union to the rule-makers in the Department of Financial and Administrative Services (FAS). An early draft of the bill included criteria like 150 trips and 30 days, but those specifics were replaced with instructions to the director of FAS to “consider factors such as the length, frequency, and number of rides provided by drivers, hours, and location.”

Matt Eng, the FAS employee in charge of hashing out the details of unionization, says “There’s a lot of disagreement on how exactly things should proceed … particularly on how drivers decide whether to get represented or not … and defining that group of drivers. That’s the critical question.” And it hasn’t been resolved yet, despite the looming deadline in September for Transportation Network Company (TNC) unionization to get off the ground. “We’re coming in on the last month and a half,” says Eng. “The ordinance calls for a commencement date, which is in September. As the law rolls out, that commencement date triggers other dates.”

The very nature of the work makes it a tricky question. Unlike, say, postal workers or longshoremen, there are wide variations in how often TNC drivers work. That’s one of the big draws—you set your own hours. It’s convenient, but creates a pickle for unionizers: Should unions—called Qualified Driver Representatives, or QDRs, in the legislation—constitute an elite club open only to full-timers? Or should someone who drove for a couple hours three months ago get the same say?

Uber, one of the largest TNCs in Seattle, wants union voting rights spread as widely as possible, in part because its entire business model is built around part-time contractors. That’s not just because the company loves democracy. More stringent voter criteria will give more power to the full-time drivers who agitated for a union in the first place, while broader criteria will enfranchise drivers with less invested in their long-term relations with the company.

“All drivers that would be represented should be enfranchised,” Uber wrote in its 33-page list of suggestions for Seattle’s unionization implementation. “The rules defining qualified drivers should be broad and inclusive.” The document also asks the director of FAS to ban strikes and “concerted activity” and nods to TNC’s reported success at reducing drunk-driving accidents, but the real sticking point, again, is how to define qualified voters, because that will determine the priorities of the new union.

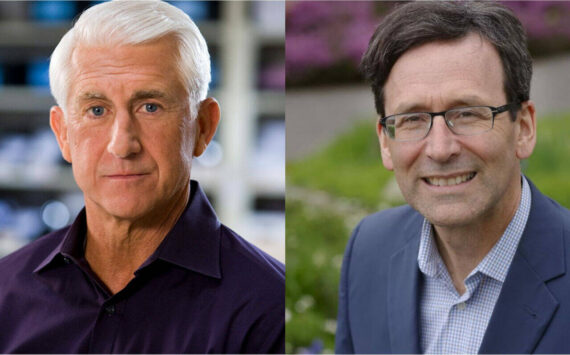

Councilmember Bruce Harrell is holding a hearing August 3 to get an update on where the city is at in writing the rules—at which both sides hope to make a final press for their interests.

Tekele Gobena, an Uber driver and union activist, says he’s tired of waiting for last year’s unionization law to go into effect. “Right now, our job has chosen to join a union,” he says, “but it is up to the city to enforce that law, and we are waiting for the city to do that.”

Gobena says that issues union organizers will bring up at Harrell’s committee meeting will include fare rates (Uber has slashed rates in the past, which financially cripples drivers for whom this is the primary income source) and consolation policy (that is, whether drivers get compensated after driving to a no-show customer). “And also the deactivation—they deactivate many drivers for no reason,” he says. Gobena is speaking from experience. Last year, he accused Uber of deactivating his account in retaliation for his union activism; the company claims that Gobena’s paperwork had expired and that they tried repeatedly to contact him before deactivation.

Teamsters Local 117 representative Dawn Gearhart says that Uber has tried to lure drivers away from unionization meetings with everything from free food to a guaranteed wage of $35 per hour for driving during meeting times. The company also sent a link to an anti-union video—but, Gearhart says, only to those identified as potentially anti-union.

“The Teamsters allegations are false,” says Uber representative Caleb Weaver. “We have reached out to our driver partners to provide information about the ordinance and to encourage them to speak out and protect their interests.”

Eng says that when he and FAS meet with Harrell’s Education, Equity, and Governance committee on Wednesday, they’ll be there to ask for guidance and time. “We’re asking them how they want us to proceed in light of the impending deadline and the amount of negotiating that remains,” he says.

For his part, Gobena has a sort of resigned optimism. “Uber is not on board,” he says. “It is obvious from the very beginning that they are not very impressed with the idea that workers will be part of a union.” Despite what he sees as obstructionism from Uber’s end, he says, “We are working to compromise. It’s not ‘My way or the highway.’

“The main issue is that this is our main job. We want Uber to understand that.”

cjaywork@seattleweekly.com