When I was 6 years old, my parents got divorced.

It was fine; it happens to a lot of kids. For the most part, they kept it civil and everything was totally OK. They are both wonderful parents. I would visit my dad in Seattle on the weekends and spend the rest of the time with my mom back in Maple Valley, which is two towns over from where that guy died from having sex with that horse, just so you know.

One morning when I was 15, I came out of the shower and found my mom and dad in a shouting match at the door. I don’t remember why it started, but I remember thinking I’d never seen my parents shout at each other like that. I watched the whole thing unfold with only a towel on from upstairs, just standing there, frozen. I felt betrayed, and naked.

The first thing I did was go in my room, shut the door, and put on Wolf Parade.

“If I could take the fire out from the wire, I’d take you where noooobody knows you, and nobody gives a damn anyway,” Spencer Krug warbled in my ears. I played that song on repeat until I felt like I actually went to that place. That place where nobody knows you and nobody gives a damn. Any place but where I was sounded really good.

The title of this piece may sound dramatic, but over the course of this project, I’ve found that it’s not that far from the truth. To help celebrate the 25th anniversary of Seattle’s biggest record label, we went out and collected your stories. We asked for your memories of the impact that Sub Pop songs or albums have had on your life. I was surprised by how much common fabric these stories share.

When I interviewed Dick Dawson, he talked about cathartically crushing cans in his parent’s garage, listening to “Shadows” by Sunny Day Real Estate. I thought back to that moment with my parents and “I’ll Believe in Anything,” and instantly understood where he was coming from. When I talked to Natalie Walker about how Sleater-Kinney very directly informed her professional career as director of the Rain City Rock Camp for Girls, I could relate. After seeing Chad VanGaalen’s video for “Molten Light,” I immediately downloaded the animation program he uses. I use that program at work all the time.

It’s funny how a record label can shape someone’s entire career. In the case of Brian Albright, who now works for pharmaceutical giant Pfizer, the stakes are even higher. If it weren’t for an obscure Sub Pop split single in 1992, he might never have met his wife.

Only a quarter-century later has it become clear what Sub Pop really is. On the surface it’s just a record label, but in reality it’s the sum of all these stories. From the first Green River EP in 1986 to this month’s release of Rose Window’s The Sun Dogs, the label’s 1,053rd record, Sub Pop has managed to put out landmark rock, folk, hip-hop, and electronica albums while simultaneously defining new genres unto themselves. But among all those records also lies a lot of humanity that isn’t listed in Sub Pop’s catalogue.

This collection of your stories is our addition to that catalogue.

Learning to Scream

Nicki Michaels is the long-haired 17-year-old lead singer of Scinite, a rock band he formed with his high-school friends in Sammamish. Scinite just released its new EP, West Coast Strut, which the band recorded with the drummer’s dad. At the time of our interview, Michaels had recently played Teenfest at Sammamish City Hall. When he picks up the phone, he informs me he’s in the middle of drinking vodka to prepare for Scinite practice. Scinite is “more motivated” than Michaels’ now-defunct punk band, Hearabout Nancy, which he describes as being “a bitchin’ little band for a while.” He started the band when he was 15.

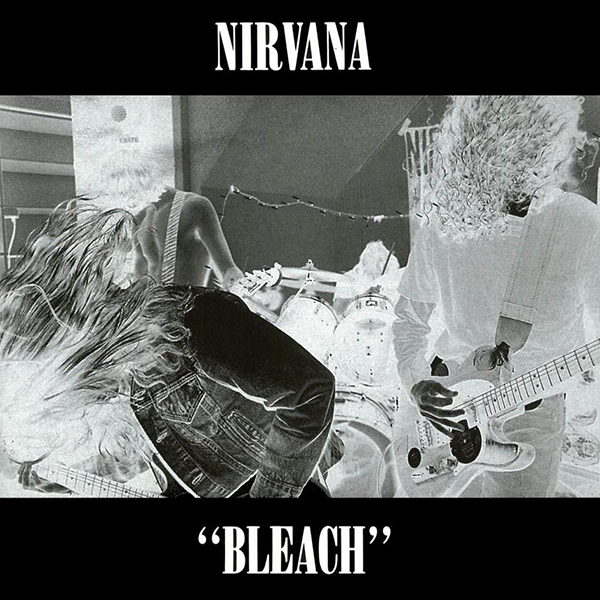

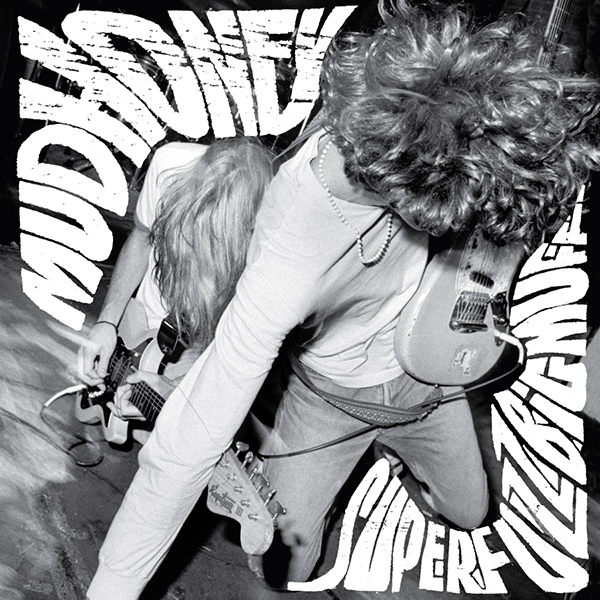

My guitar teacher told me about this movie called Hype, about the early-’90s grunge scene and how Sub Pop rose to power and all that. I think the first song we ever played [in Hearabout Nancy] was “Touch Me I’m Sick” by Mudhoney. We played a ton of Mudhoney covers. We would go into our garage and we would plug a microphone into a guitar amp and we would just scream those songs. When we were warming up, we would play the entire Bleach album and [trade] off our instruments and stuff. That was so fun. We used to rock, like, “Floyd the Barber” and “Blew.” Uh, “Paper Cuts” and “Big Cheese” and “Swap Meet.” We played Mudhoney a lot too. We played shit like “Sweet Young Thing Ain’t Sweet No More” and “Hate the Police” and “Flat Out Fucked.” Oh damn, it was good stuff. [Nicki goes on to list nearly every song in the Mudhoney catalog.] Oh my God, I can’t even remember all of them. All those songs, that was our stuff.

First song I ever learned to play on guitar was “Polly” by Nirvana. I learned all the early Nirvana riffs. I still to this day can play Bleach from the top to bottom, and I can play a highly butchered version of every single solo. I would sit in my room late at night, and me and my friend Mark would listen to Bleach. We’d play it for five seconds, then pause it. Then we’d sit down and play that five seconds on guitar. It was the same thing over and over until we could play the entire album. We’d take Adderall. Like, speed. A couple days of doing that, and then we came out of my room being able to play the entire album.

When we did start writing our own songs it was very Bleach-esque. Raunchy lyrics, tuned-down drop-D guitars. It was more about the aggression of it, not so much the musicality. You could just write about anything and then scream a loud chorus.

The Hell Out of Denver

David Clifford is the founder of Us/Them Group, a Los Angeles-based artist promotion company. He is also the drummer for the band Red Sparowes.

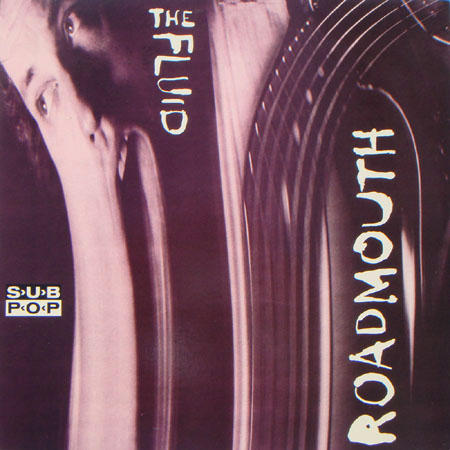

It was June 1989 in Denver, Colo., when I bought Roadmouth by local heroes The Fluid. It was a fateful day in which I bought that album, Steel Pole Bathtub’s Butterfly Love (themselves a former Denver band, now making an impact nationwide), and Dinosaur Jr.’s Bug. I’d seen The Fluid live, and their MC5-infused retro-garage punk seemed nothing like what I’d heard in Mudhoney’s sludgy “Touch Me I’m Sick” single. But it wasn’t until hearing The Fluid’s second Sub Pop album paired with the noisier works of STB and Dinosaur Jr. that it all seemed to make sense in a way that things were all headed in a really exciting new direction of beautiful noise. And it meant that if The Fluid could get out of Denver and become pioneers, then I should dare to give it a try as well.

Years later my own band, Pleasure Forever, signed to Sub Pop. I had a very fancy job working for a fancy record label, with expense accounts, living bicoastally between San Francisco and New York City, etc. I gave it all up just to make a record for Sub Pop. And though very little came of it, I don’t regret it in the slightest. I made some great lifelong friends at the label, toured like crazy, and had some incredible experiences, all due to that lone, crazy record label that changed my life back in 1989.

Going Grunge

Chris Conkling, now in his 40s, grew up as a misfit in the Bavarian-themed tourist town of Leavenworth in the early ’90s. “It was kind of like a theme park,” he says. “It was pretty weird.” He now lives in Renton and runs his own independent Northwest-music blog, donewithaplomb.wordpress.com.

Leavenworth was an odd town to grow up in. You knew everyone, it was pretty secluded. This was pre-Internet, so I didn’t have access to the wider music scene. I used to drive down to Wenatchee and pick up Alternative Press or some other cool magazine like that. And I think I first heard about Mudhoney from a Sub Pop comp, The Grunge Years. There was a Mudhoney track on there, and I went out and bought their most recent record. There was nobody playing stuff like that on the radio out there, and they weren’t on the air on MTV or anything yet.

When I liked a band a lot, I would write them a letter or fan mail or something. I wrote Mudhoney a letter. I knew they were a pretty shocking band, so I tried to write them a pretty shocking, out-there letter to grab their attention. They actually wrote me back and thanked me for being a fan. I don’t even remember what I wrote the letter about . . . some crazy thing. I was just trying to be cool to the rock stars.

Interacting with a band back then, pre-Internet, was a big deal. It gave me more confidence in who I was and what I wanted to do, and what I do today.

They also sent me a sticker . . . it was an orange sticker that said the band name on it, so I slapped it on the bumper of my car. I was driving a ’67 Ford Falcon; it was awesome. I’d be driving around this small town. I’m a pretty quiet kid, everyone knew who I was, and all of a sudden I’ve got this Mudhoney sticker on my car and I’m blaring Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge. That album meant a lot to me. I got a lot of strange looks, and some ribbing from my family at my attempts to “go grunge.” That band was exactly what I needed at that time in my life. They will always be my favorite band of the era.

Journey to the Center of the Universe

Brian Albright has the dubious, self-proclaimed honor of being the first guy to launch Viagra into the Seattle market. Before doing marketing and PR at Pfizer, one of the country’s largest pharmaceutical companies, he was the manager of his college radio station at the University of Connecticut from 1987–92.

Signing up for the Sub Pop singles club at the radio station, it was the coolest. They started off sending out singles with their sort of signature Seattle grunge sound, but quickly they started doing all sorts of other stuff. They were highlighting bands they liked that were not on the label. Nobody was doing that at the time. They were pioneers.

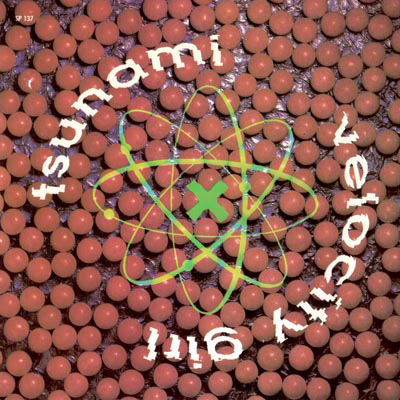

What I like in music is really this fuzzy, crunchy, indie-pop sound. They were really good at that, but it was so varied. Reverend Horton Heat, Billy Childish, Thee Headcoats, which has sort of a cult following in London, but I’d never heard of it before that Sub Pop single. The thing that kind of sealed it for me, though, was in 1992. It was one of the last singles they released before I moved to Seattle: Tsunami and Velocity Girl. At the time, Velocity Girl was my all-time favorite band. It was like, “OK. These guys [Sub Pop] are the coolest people on the planet.” It, just, I, it was . . . [Brian stammers for a moment in excitement.] It was like Seattle was the center of the universe. It was unbelievable. You know, at the radio station when Nevermind came out, it really was like the perfect record. But these singles, they were the icing. And then Seattle, the cake, was there waiting for me to come and take a bite out of it.

Having been in radio before, I had some contacts here. I landed this gig as music director of this company. Any department store in the country, whether it was Macy’s, Nordstrom, JCPenney, Sears, all the way to Toys “R” Us—anywhere in the country you would go and see music videos playing on TVs, from ’92 to ’93, that was me. That was me picking and making all those shows throughout the country. We literally had the contract for every single department store. It was great, but, as you can imagine, after days and days, you start to get kind of numb.

I got fired for showing this silhouette of Gloria Estefan laying on her side . . . you couldn’t see anything, but you could tell that she was naked. The manager at the Toys “R” Us is looking up at the monitor at that exact split second [laughs]. Oh, man. That was the end of that career.

It was a good time to lose that job. It brought me to a new job working at Orpheum Records on Broadway up on Capitol Hill. That was not far from where Cobain was living at the time. Every rock star would at least stop through, but Cobain was a regular. He would come up and be like, “What’s new, man? What can you show me?” At the time, that was like absolute, utter heaven. I was like, “You’re asking me?”

We would talk about all these obscure things. Cobain had really expansive taste in music, he wanted obscure stuff. I remember we were having a hard time tracking down the Pontiac Brothers, which is like, you know . . . “Who?” We would talk Guided by Voices. He was really into all that stuff.

How crazy is that? I feel pretty blessed that for years I sort of lived my dream. That was what I wanted to do. I wanted to come here, I wanted to be immersed in the whole scene. And you know, coming out here I did meet my wife.

Crush and Release

Dick Dawson was raised in Duvall. As a young man, he fancied himself a budding guitar hero. Dawson played in bands around the community, including a couple of shows at the Redmond Fire House and one memorable set opening for some of the guys in Mudhoney. His parents were “educated hippie types,” and took him to lots of rock shows growing up. He still plays guitar.

In the early ’90s, I was really into Seaweed, who were a Sub Pop band at the time. I’d seen them a number of times, like at the Pearl Jam Drop in the Park show. I found out that they were playing at the Mural Amphitheatre for the Pain in the Grass series. When I got there, there were all these signs around that said “Sunny Day Real Estate.” I was clueless at the time, and kept asking my dad if they were planning on selling the Mural Amphitheatre. So then Seaweed starts to play, or what I think is Seaweed starts to play, and at the time, Jeremy Enigk and Aaron Stauffer, the lead singers, had similar builds and haircuts.

So Sunny Day Real Estate starts playing, and I think it’s Seaweed. I start rocking out, and then Seaweed comes on after, and I was like, “Oh.”

Right after, we went to Silver Platters, and I bought Sunny Day Real Estate’s new record. It’s been my favorite record ever since. That was a really interesting way of coming upon them.

In “Shadows,” there’s this part near the end of it where they do this different kind of break and he does this neat fuzzy guitar. I could sing it for you, but I’m not sure that’s going to be helpful. [Dawson begins enthusiastically making guitar wail sounds.] Like that. Oh, right, and then he starts saying something about “Leaves falling short . . . ” uh . . . “dream’s over.”

The first time I heard that song, I was crushing cans in my parent’s garage. They just would drink soda pop like crazy. There were always those black Glad bags just filled with aluminum cans, and I would take that CD down there with me. That was the soundtrack to a number of stomping sessions. It was the second CD I ever bought for myself with my own money. That must’ve been ’94, so I was what, 15?

[I ask Dick if he ever resented having to stomp his parent’s soda cans at that age.] Oh, yeah. We never got any soda. It was a menial task; I was a kid who didn’t really like doing chores. The first time I heard “Shadows,” I must’ve backed it up and played that one part like 15 or 20 times. There was something about that guitar tone—just that part of the song really got to me, it really spoke to me.

It felt like a palpable sense of release. There’s just a change of mood in that song. When that part comes on, it sounded triumphant, but yearning at the same time.

I think it was just that I was 15, I was a guitar nerd. I was just starting to teach myself guitar, really starting to find my voice. That song, that record—there was something in the way everything was phrased. When I listened to Sunny Day Real Estate, I felt like I’d found a kindred spirit.

Growing up in Duvall made it a little bit more difficult for me. I was perhaps a bit more progressive than some of the people who grew up with me. I wore my hair long. They used to call me names. I was skinny. I can’t tell you how many times I got called a fag. To be honest, I was a bit of a provocateur. Some days I’d wear fucking barrettes in my hair. I knew that it was going to piss off those people. But it didn’t matter. There’s just something so cathartic about being able to listen to a song and having it exorcise whatever feelings, or support whatever feelings, you might be brooding over. Sunny Day Real Estate did that for me.

Where the Strings Come In

Jacob McMurray is the curator of the Experience Music Project at Seattle Center. He recently put together an exhibit called “Nirvana: Taking Punk to the Masses,” which found him in the attic of bass player Krist Novoselic, looking through old boxes.

I’ve never been a Sunny Day Real Estate fan, so when Return of the Frog King [the solo debut of lead singer Jeremy Enigk] first came out, in ’96, I sort of dismissed it. But there was this big article in The Rocket sometime around when that record came out that was about Jeremy Enigk and his conversion to Christianity with that record. I think in a way it was weird that there was so much press dedicated to his religious beliefs, but I don’t know. That article described the record and all the orchestration and everything, and I remember picking it up.

I was 24, living in the U District, going to the University of Washington working on an archaeology degree. I think what was really interesting was that all the stuff I loved at the time right specifically then was, like, Built to Spill, Modest Mouse, Violent Green—you know, a lot of pretty full-on mid-to-late-’90s indie rock—and this was so different than that. I think that’s why it made such an impact on me, and why people either loved it or hated it, because it was pretty atypical for what was going on at the time.

I still think I’m sifting through that record today; it’s a phenomenal record. It’s about a half an hour long, and you know, it’s just him with an acoustic guitar and a 21-piece orchestra or something like that. What I loved about it, and what I still love about it, is that it still pushes the same buttons in me as Wizard-era King Crimson or the first Roxy Music record. It kinda has this sort of baroque, almost medieval sensibility to it. I don’t know—he has such a beautiful but rough voice. It’s really moving.

Letter Bomb

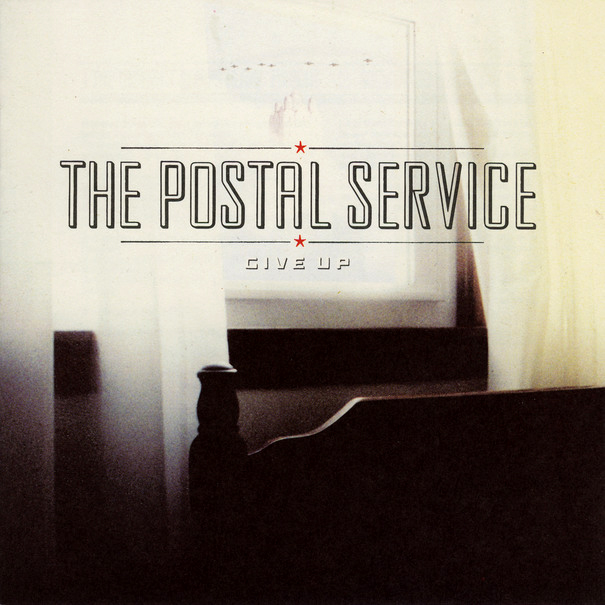

Scotto Moore is a 41-year-old recovering music blogger from Seattle. He spoke to us at the Sasquatch! Music Festival the day that The Postal Service was playing, 10 years after the release of the group’s only record, Give Up.

I was a music blogger for six or seven years, and I heard Give Up when it first came out. And I knew it was going to blow up when I posted two or three tracks on my blog and my servers basically almost crashed. People were so excited about it and pounded my servers. So later, when they released “Against All Odds,” I actually had to rename it—and tell the people who were reading my blog “This is Barry Manilow”—so my servers wouldn’t be pounded by anyone other than my regular fans.

As someone who was really paying attention to music at the time, it seems a little cliche, but they certainly invented this entire style. And for years, you would hear bands that would come along and be near-misses—trying to capture that magic of the digital side and the acoustic side. Because if you listen really closely, it’s not just “bleepy-bloopy,” which is the electric part of it. But it had the vocal richness, and you could hear the guitar in there, and I think a lot of people overlook how dense the sound is. And it’s not just computerized.

“District Sleeps Tonight”—there’s a remix of it that when I DJ just totally kills. And I’m absolutely in love with how that works.

The Laws of Thermal Energy

Witt W. is the very tall 29-year-old guitarist and lead singer of an Atlanta-based folk-punk band. He hasn’t shaved in a while, and covers his long mop of hair with a beanie. I caught his set after his set at Victory Lounge out on the deck, where he sat down for a cigarette. His bandmates mentioned to me earlier that he has tripped the South American psychedelic plant ayahuasca a number of times. I ask if it’s OK if we talk about it, and he emphatically insists that we do. “More people need to hear about this stuff,” he says, “it’s really important.”

The first time I went, you go and everyone is in a circle. The shaman takes ayahuasca with you, and he’s learned these songs that he was given by the plants. Over the course of his life he’s developed this repertoire of songs that sometimes aren’t in any decipherable language. They’re just melodies and words that come to him. His power and his status grows with the more songs he has. The whole six hours he’s singing songs that kind of guide the energy of the trip. If it gets really dark and he knows everyone in the group is feeling that energy, he knows the right song to get the energy back up. It’s very musical.

I was raised Jewish. At a certain point the shaman’s songs all start sounding like very ancient Jewish Hebrew songs to me. To me it’s the most quintessentially religious experience anyone can have in the modern world. We’re not, like, a psychedelic band, but our last album was almost entirely written from my own personal psychedelic experience. I had a friend that passed away last year, and psychedelics were really important to me in understanding the space that he moved on to. You’re having an after-death experience with this stuff—you are forced to kill your ego and have an objective sense of yourself, which is impossible normally. It made me think a lot about “Where does melody come from? Where do these lyrics come from?” I do think there’s some kind of energy-channeling that’s happening.

Even at punk shows, man, it’s 30 minutes where people get out their anxieties, what they have to do tomorrow, their regrets. It’s 30 minutes of being in the moment; it’s almost transcendental. I think when you are feeling an energy exchange, you are experiencing the real idea of the gestalt in its physical manifestation.

There’s a sense of sincerity or authenticity when you watch bands. Even if they’re technically good, you just know if this is something they’re trying to do. You sense that ego.

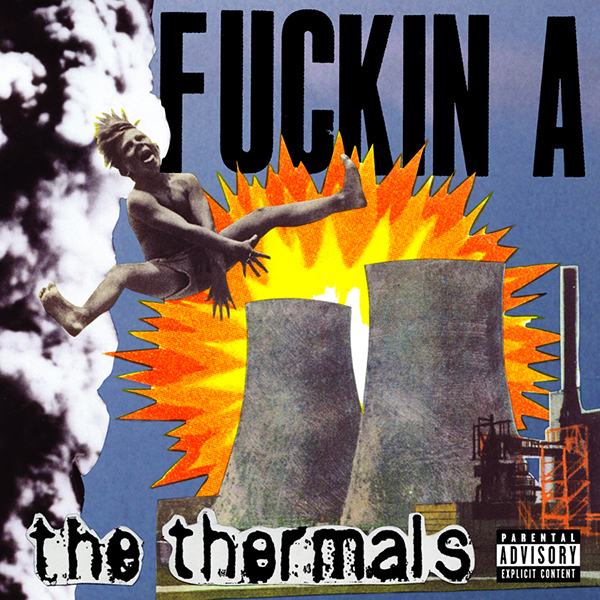

I love the Thermals. I think the Thermals are one of the most authentic, sincere bands. That’s why I respect them so much. Good songs . . . there’s this idea that you are channeling them from somewhere else, you are like a conduit. The Thermals do that.

Fuckin A to me, just as a whole album, is the pinnacle of what they do. Fuckin A is the album, man. As a cohesive unit, it’s amazing. They made that album as a cohesive thought. I think they are intentional about the flow of the album, the sequencing. I don’t think it’s a technical thing they’ve got going on. It’s just when you see them live, they’re locked in. They’re one of the few bands that do that. They channel that energy.

They’re a band that goes for energy over technicality. I think that’s really important. When we record, we record live. We go for the take. It may be a take with a missed note or a missed hit, but when you finish, you just know that this one is it. There’s this ephemeral energy to it. Like, let’s keep that one. Everybody kinda finishes, and everybody wants to be quiet for a few seconds so nothing bleeds into the recording. But in those seconds, if it’s the one, you kinda feel it, and everyone looks around and it’s like, “Yeah. Mm-hm.” [Laughs.]

There’s this balance that bands should have between not sounding like shit live, but also being able to present this certain amount of energy. A lot of bands will get really sloppy when they get energetic. The Thermals have that balance; there’s this full sound and they’re playing really well, but there’s this . . . they are just giving away this energy. When you watch them, you are, like, “These guys are working hard. I want to be a part of that.” That’s what’s really important. I truly believe that. It’s all about exchanging that energy.

Speakers Blown

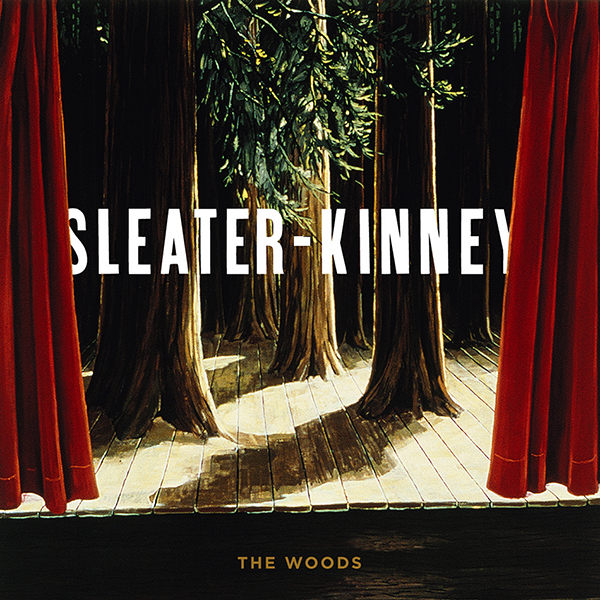

Natalie Walker is the director of the Seattle-based Rain City Rock Camp for Girls, “a nonprofit organization dedicated to building positive self-esteem in girls and encouraging creative expression through music.” Over the course of a week, girls at the camp choose an instrument, form a band, and write a song together which they later perform at a real rock venue in town. Walker herself plays bass in an all-female rock band called Another Perfect Crime. While interning for music journalist Everett True in 2005, she got her hands on an advance copy of Sleater-Kinney’s last album, The Woods.

Everett had just gotten done interviewing Sleater-Kinney for, I think it was Plan B magazine? They had just gotten done mastering The Woods in January or February of that year, but they weren’t releasing it until May. So anyways, we are driving around in the car, and he goes, “I JUST GOT A COPY OF THE NEW SLEATER-KINNEY ALBUM, IT’S RIGHT HERE,” and I just went “WHAAAAAT? I CAN’T BELIEVE YOU HAVE IT. I AM THE BIGGEST FAN.” So he puts the CD in the CD player in my car, and the first track comes on, “The Fox.” It’s just, like, kind of growling at us, and we both look at each other and go, “Wait. Did they give you the right CD?” We did not think it was them [laughs]. But then of course Corin Tucker comes in with her crazy wail growl, and we were like, “Oh, OK, this is obviously them, but is there something wrong with the CD?” I mean, it was amazing and awesome, but it sounded really off in some places. Like, “Are my speakers blown?” Like, “It sounds like there’s bass. Did they get a bassist?” I remember Everett looking at me and going, “Wow, they went to Sub Pop and now all of a sudden they sound grunge” [laughs].

That was a really cool moment for me. I’m a huge super-fan, and I’m listening to the record before it is released, and it’s everything I love about the Seattle sound and the Sub Pop sound, and my favorite band is now kind of embracing that too.

The track on that record, “Modern Girl,” is one of my favorite tracks ever. Ever since I heard it I’ve been trying to write a song like that. I haven’t quite gotten there. It’s like, you know, this really bleak kind of thing, and then toward the end when the band comes in, your speakers get blown.

I guess it’s just the contrast. It’s the really pretty guitar line, the simple beginning, and the lyrics, going from really happy to “I’m really pissed of” by the end . . . it’s just the perfect song.

One hundred percent, Sleater-Kinney informs what I do at Rain City Rock Camp now. It was seeing them live that encouraged me to start playing music, you know, in a rock band. It took having a same-sex role model doing that to get me onstage. Knowing that informed the creation of this rock camp, where we’re basically saying “Hey! Here’s a bunch of role models.” We’re just going to put that in your face. They’re going to be your teachers. They’re going to be your lunchtime performers. They’re going to be your role models, and we’re not going to make it hard for you to find them because they’re all here at camp. It really directly influenced that.

Tale of Two Cities

Annie Holden is originally from Phoenix, Ariz. She recently graduated from the University of Washington. Holden has worked on marketing and communications for Seattle’s all-ages venue, The Vera Project, for a little over a year now.

I knew I was coming to Seattle for college. I really liked all of the local music coming from Seattle; I loved Fleet Foxes. So I go to the local record store in Phoenix, like one of the coolest places, and I say to the guy working there, “Hey, so I’m moving to Seattle soon. Do you have any recommendations of local bands? Here’s a list of bands I like, would you have anything else?” And he goes, “Oh yeahhhhh. Seattle. For sure.” He walks me over and gives me Blitzen Trapper’s Furr. I hop in my car on the way home, and I really like it. It’s become one of my favorite albums of all time—BUT . . . I was telling my friend about this awesome band from Seattle, Blitzen Trapper, and they’re like, “Uh, no. They’re from Portland, not Seattle. Portland and Seattle are very different.”

That’s when I started learning about the weird music rivalry between the two. I mean it makes sense that the record-store guy would do that to me, because, you know, Sub Pop and Seattle, but . . . I don’t know. I just always feel mad about it. Like, he lied to me, you know?

I was just, like, “I wanted Seattle music, not Portland music. That’s so different.” But I mean, it’s all the Pacific Northwest. That album gave me so many preconceived notions about the Pacific Northwest before I got here. I’d only been here once before. I guess I really thought I’d be going into the wilderness a lot and . . . morphing into a wolf or something. Maybe one day, but not yet. Blitzen Trapper let me down, even though it’s a great album, and I love it.

Call of the Evergreens

Joseph McGeehee is a prolific artist and a recipient of the Sub Pop Scholarship, a program started by the label that doles out money to help young “losers” pay for college based on their weird talents and freaky interests. I was lucky enough to have won a scholarship in 2009; McGeehee received his in 2012. His work features melty, surreal forms and landscapes that are often either dripping or levitating. A student at the Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland, McGeehee recently held his first gallery show, Metamorphic Forms, and released the first issue of his comic series The Impossible Future, about a dog and a boy and their botched attempt to make home brew. His work can be viewed at artistflu.tumblr.com.

I have a really strong memory of being on the 550 bus, the express bus from Bellevue to downtown Seattle, and we were going across the I-90 bridge. It was a beautiful, sunny day, and I was listening to “Grown Ocean” off of Helplessness Blues. I was so overwhelmed by the beauty of the Pacific Northwest, just with how much I love it here. That song always brings up the strongest sense of loving the place where you live. I think it really vibes with the feel of this region. It definitely feels like somehow the song is a part of the region itself.

That was my senior year of high school, and I guess that’s another part of it. That was in the midst of my big decision time: “Am I going to leave the Pacific Northwest to go to college?” I was really looking at the Art Center College of Design down in Pasadena. I don’t know. I visited the school. I liked it. But I couldn’t see myself living in L.A. at all.

It was a really hard decision. On that bus ride, that song just really intensified this strong connection I feel to this region of the country. It intensified my appreciation for everything that is the Pacific Northwest.

I also just love the laid-back energy here. In Portland it’s really encouraging to be strange, and outwardly so, which I think is really conducive to art practice. You don’t get that kind of encouragement most places. Every time I listen to Helplessness Blues, it’s just all about thinking about your life, and the scope of your life, in relation to this larger thing. You know, where you live. I think maybe it’s an aesthetic attraction for me—like, maybe instinctively I want to call evergreen trees and sweaters paradise, because they resonate so deeply for me. I just feel like I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else when I listen to that album.

Mellow Strong Sexy

Michelle O’Connor works with Natalie Walker at Rain City Rock Camp for Girls as an instructor.

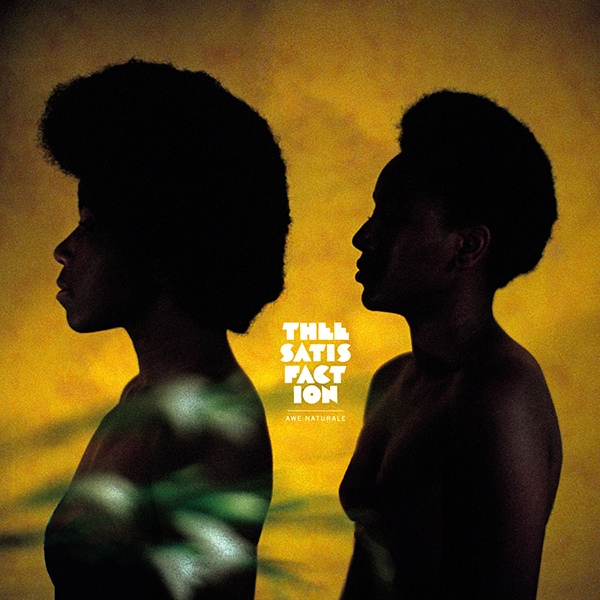

When I think of my fave Sub Pop songs, I immediately think of “Queens” by THEESatisfaction from AwE NaturalE.

First of all, we all were so excited about this album being released on Sub Pop. It was like one of our own was getting the recognition they deserved. And the album itself is incredible. Unique, smart, and unlike anything I had ever heard in hip-hop . . . or ever.

When I first heard “Queens,” it blew my mind. From that mellow, sexy intro directing us to leave our BS at the door and let loose to the infectious “Don’t funk with my groove” hook, this definitely has always meant cool female empowerment to me. Like, “This is how it’s gonna go down, sister. So there.” It’s just one of those hooks you wish you wrote.

So after spending a few weeks obsessed with the song, I was moved to write my own, with that mellow, strong, sexy vibe as inspiration. This song still makes me want to be as cool as Cat and Stas.

Additional reporting by Mark Baumgarten and Keegan Prosser.

Sub Pop celebrates its 25th anniversary with a Silver Jubilee on Sat., July 13, in Seattle’s Georgetown neighborhood. The free event will feature performances by many of the label’s artists. For a full lineup, go to silverjubilee.subpop.com.