Two weeks ago, The New York Times confirmed the long-circulating rumors that Jay-Z will be stepping down as CEO of Def Jam Records, a position he’s held for three years. Supposedly, Universal, Def Jam’s corporate owner, balked at Jay-Z’s salary demands. If one were to take his lyrics at face value—a dicey and unsporting proposition with any artist—Jay-Z’s high asking price should be no surprise. After all, this is the man who broke ground not only as the first rapper-turned-CEO of a company not of his own creation, but also as the first person to publicly brag about “raping” his label and then become its CEO (“I’m rapin’ Def Jam ’til I’m the $100 million man”). He boasted that his avarice served to avenge the slights of his musical predecessors, who were never paid their due. (“I’m overcharging niggas for what they did to the Cold Crush.”) What all this amounted to, however, was a moderately successful three-year stint, some low-level layoffs, and a denied request for more money and its accompanying problems.

While the man who calls himself J-Hova has no shortage of wealth and enterprise on which to fall back (among other things, he is owner of a clothing line and co-owner of the New Jersey Nets), his departure from Def Jam still rings a little disappointing. The thing is, more than most rappers, Jay-Z’s success is wrapped in, or wrapped around, legend and myth. Plenty of rappers have gone from rags to riches, but few have made their success seem so inevitable and versatile. 50 Cent ran a more than impressive street game (are there any similar journalistic accounts of Jay-Z’s skills as a hustler?), was pumped so full of lead he could’ve been a pencil, and then had the acumen to buy into VitaminWater in ’04, ultimately cashing out to the tune of $400 million. And yet he doesn’t possess anywhere near the mythic stature of Jay-Z. Of course, a lot of that has to do with musical prowess, but more on that in a bit.

In moving from the hustle to the boardroom, from the eternal elephant in society’s living room to the very picture of establishment success, Jay-Z achieved the dream of celluloid gangsters as disparate as Oscar‘s Snaps Provolone, Haymaker & Sally‘s Lincoln Playa, and The Wire‘s Stringer Bell. He’s gone “legit,” something he frequently celebrates in his lyrics. Now that he’s completed the full arc of the hustler-made-good, he’s above needing to prove himself in any realm (“I don’t want much, fuck, I drove every car/Some nice cooked food, some nice clean drawers”). The problem is, making good is one thing, staying good another, and staying good in the public eye, in the mythopoeic, hardscrabble American Dream sense, yet one more. When a gangster gets taken out, it’s a blaze of glory, or at least an acceptable price for having lived the high life the hard, fast way. But nobody ponders Vito Corleone’s offers and turns them down, and it’s hard to imagine Horatio Alger’s protagonists watching their ass for a closing boardroom door.

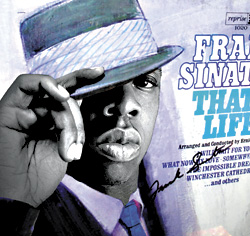

Jay-Z likes to compare himself to Frank Sinatra, which is a little unfair to himself, as his own rise from nothing to real chairman of the board required more industry and acumen than did Sinatra’s Jersey-to-Vegas, chairman-in-nickname-only climb. Moreover, with his lyrics, Jay-Z penned his ascent, wrote his own legend. But strangely, unlike Sinatra and even purely fictional characters like Stringer Bell, whom Jay-Z perhaps most resembles, he sometimes seems ambivalent about moving on. Sinatra didn’t boast of his shadowy associations, and Bell—his desire to put a hit on Clay Davis notwithstanding—dealt with a tight spot by looking to Milton Friedman or Bill Gates. Jay-Z looks to Frank Lucas and his own memories of the street game. The hustle is what makes him tick and drives his best rhymes. Guilty pleasure or not, last year’s American Gangster, like Reasonable Doubt (1996) and The Blueprint (2001), is compelling stuff.

Yet given how self-glorifying the rhymes invariably are, and given their author’s remarkable dexterity and cleverness with the English tongue and his boasts of being able to conquer any endeavor, even his fans may sometimes lament that he hasn’t managed to bring the same intelligence and enthusiasm to other subject matters. Or perhaps that he hasn’t more fully explored the internal conflicts of the street game’s players and especially bystanders, however textured and attractive his current portrayals may be.

You could argue that hip-hop is held to different critical standards than other genres, and not just on the subject of public morals. Martin Scorcese’s been telling the same ol’ gangster tales for decades, and we all still cheered The Departed. He attempted a number of departures, but then, many of them weren’t very good. And of course, he’s had an extra 30 years with which to experiment. Jay-Z’s only 38, so this should probably stop reading like an obituary; he still has plenty of time to experiment, and he’s given us no reason to believe any claims of retirement. Will he move beyond the hustle? Maybe it’s that you can take the kid out of the street but not the street out of the kid. Maybe the market failed him, and like a good hustler, he tells us only what album sales say we want to hear. Or maybe, as Vladimir Nabokov once said, “Derivative writers seem versatile because they imitate many others, past and present. Artistic originality has only its own self to copy.”

This piece originally appeared on SW‘s Reverb blog at www.seattleweekly.com/reverb.