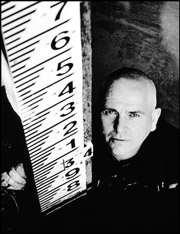

PETER GABRIEL

BLIND BOYS OF ALABAMA, HUKWE ZAWOSE

KeyArena, 206-628-0888, $39.50-$96.25

7:30 p.m. Tues., Dec. 17

PETER GABRIEL is giggling.

Most people laugh. Even the dourest among us enjoys an occasional guffaw. Yet there’s something odd about listening to Gabriel, at home, chuckling through the giddy, antic screams of his 1-year-old son that’s almost shocking to hear.

After all, so much of Gabriel’s work—from the theatrically inclined Genesis to his jagged solo efforts, even the ripened R&B of “Sledgehammer”—revels in a brittle and a forlorn quality perfectly suited to his dense art-rock soundtrack: a vexing visualist noise that has been married to the works of directors like Alan Parker (Birdy) and Martin Scorsese (The Last Temptation of Christ, Gangs of New York) and made Gabriel a stunning video maker.

Still, he’s laughing all the same. The reason? Up.

Ten years and a rumored 150 songs after his last album, Gabriel’s recently released Up is less personal than previous records but equally affecting, utilizing moody water/moon metaphors to capture the intricacies of the life cycle, beginning to end.

That crepuscular texts are run through textural tribal beats, Satie-styled piano fills, and eerie electronics—as well as the usual fractal contributions of old pals Tony Levin and David Rhodes—makes Up as frighteningly new and warmly familiar as Gabriel is in conversation.

Seattle Weekly: In terms of your personal history, I can only remember you doing music. What was the last proper job you held?

Peter Gabriel: I never really had a job. I did, however, when I was in school, sell hats. Not a haberdasher, mind you, but a would-be hippie entrepreneur. I wasn’t getting much pocket money during my last years at school, and it just happened to be the time when all this psychedelic stuff was breaking out in London. I found this old hat in my grandfather’s costume box, probably from the 1700s. I thought that it would be great if I had it done up in colors. So I managed to get some produced in the most wild psychedelic colors by some fine old gentlemen’s outfitters—Dunne & Co. They looked at me—this strange schoolkid—as some sort of novelty. I managed to take them around to Kings Road and sell a few. Never knew to who at first. But one of the highlights of my school days was watching my favorite music TV show, Juke Box Jury, and seeing Marianne Faithfull wearing one of my hats. Not too long after, I sold another one to Keith Richards. I was very proud of that. Scored a lot of points for myself in school.

After that, it was either stay in school to learn filmmaking or go into music. I went straight to music and never did an honest days’ work in between.

Still, for a musician, that’s an auspicious start: “I sold a cap to Keith Richards.”

Not really. We couldn’t get arrested in the early days of Genesis. No work. No gigs. Believe me, we were looking for alternatives.

What did you do with all the grand costumes from Genesis—those huge heads from the Foxtrot tours and such?

Some we tried to keep. But so many of them—like the grotesque character I had called the Slipper Man—were made of rubber. Unfortunately, the latex rotted. Still, there’s a few pieces that survived nicely intact and are kept in this junk area where I stash all of my paraphernalia.

After careful thinking, I came to the realization that, despite the long shadow of influence you cast, I couldn’t think of one particular act who’s been able to copy you. Do you hear what you’ve done in any one artist’s sound?

I think I was part of a process, with a group of others, who introduced world elements into music. I’ve always liked unorthodox, weird, wonderful sounds. That may be the main thing. On the writing side, I think some of the harmonic stuff I did with Genesis has had reach on others. It certainly stayed with me. I wouldn’t say there’s anyone specific, perhaps because I’m a jack-of-all-trades-master-of-none thing.

Up feels like a slightly less personal record. Why?

My last record was more about direct relationships. I think this one’s an observational record about how a 52-year-old man fits in this world—a father, husband, etc. It is personal in that the 52-year-old happens to be me.

I’d be hard-pressed to guess what religious beliefs you hold. But there always has been a sense in your music of grasping for something higher.

What we’re fed as kids—the white man with the beard in the sky— I never bought. But on a song like “More Than This”—along with a lot of my work— there is a longing. I always wanted something present and balanced. So there’s a spiritual urge that’s undeniably there.

The song “My Head Sounds Like That” feels as if you’re trying to quell panic.

It’s like that dull, dampened moment where you pick up on a particular sound. Like when you throw up, you have a heightened sense of smell. Very alive. That song is about my heightened sense of hearing.

People often ask the question: “Why would it take you 10 years to make a record?” What I want to know is how you maintain instinct across that amount of time. Up feels very instinctual.

When I was in school, uncertain as to what to do with my life, not good at much of anything academically or artistically, I was sent to a career guidance specialist for psychological analysis. The two things that came up for me were photographer and landscape gardener. I thought, at the time, it was a joke. But the older I get, I see there’s quite a lot of wisdom in that.

I work like a photographer in that I find the moment that is hot and interesting and freeze it—on tape, on computer. Then, as a gardener, I take those moments and plant them in the landscape, in a visual environment, and let them grow slowly, clipping the leaves every few months. One is a slow process, one fast. By combining those, I try to preserve the most fiery elements. There is an ultimate danger of overworking stuff. But [co-producer] Tschad Blake is also the king of the mute button, so if I ever lose sight of the initial snaps, he locates them.

You mention the visual landscape thing. Do you think it’s that sensibility that’s made you valuable to directors like Alan Parker, Philip Noyce, and Martin Scorsese? What is it they heard in you?

Parker saw the landscape quality immediately, knew it would serve his vision well. I think Birdy is a terribly underrated film.

With Scorsese, it was like this: Ask a man a question that you know he won’t know the answer to. If he does nothing, he’s an internalist, working from within. If you look around the room for clues, you’re a visualist. With Scorsese, I’ve been the latter. Having seen the things I worked on with Marty before music and after, I can tell you my music and his images are a happy marriage. There’s tension.

I can hear your baby laughing in the background. It makes me think about “Darkness”—probably the most childlike of all your songs, as well as the most wholly generational. How crucial was his birth to all that?

It’s funny how the age thing is cyclical. You can hear the 1-year-old in the background, my dad is 90, and I’m 52. There’s a consciousness beyond the thrust of needing to succeed within the immediate. You lose the sense of needing to find yourself in that realm—opting instead to see how you fit in a slightly bigger picture that might include the sea and the sky.

Yes, but with all the big-picture stuff, what’s making you laugh out loud?

Truthfully, this young man here is a constant font of enjoyment. He’s got an amazing sense of humor.