Last week, Seattle-based Light in the Attic Records became the first label to release Serge Gainsbourg’s Histoire de Melody Nelson in the United States. Knowing this, the question is: Why didn’t anyone else ever think of doing it?

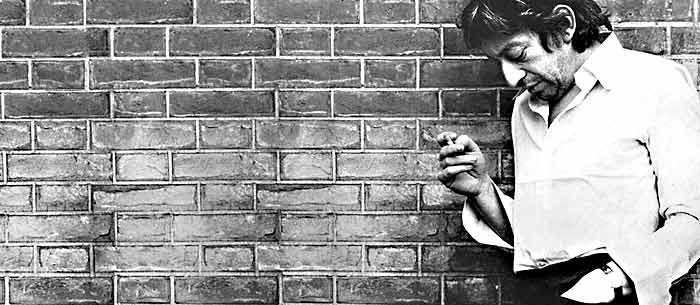

Matt Sullivan doesn’t know either, but as LITA’s head honcho, he’s glad no one had. After all, the 1971 album is widely considered one of the most groundbreaking albums of all time, and Gainsbourg, the petite Frenchman behind it, one of the most influential musicians in the world. The album’s sensual blend of rock and orchestral arrangements has been openly slobbered over for decades—and not just by record geeks: Beck’s album Sea Change was a blatant Melody Nelson ripoff.

“[Music fans] are always saying ‘Oh, well, such and such is a masterpiece,'” says Sullivan. “But Melody Nelson really is a masterpiece. It’s the Sgt. Pepper’s of French music.”

Reissuing legendary albums is LITA’s stock-in-trade, yet Histoire de Melody Nelson stands out in the label’s catalog (and not just because the cover boasts a topless Jane Birkin). It’s the label’s first foray into Francophilia, and the first album they’ve dealt with whose creator was a legend in his own time and whose popularity hasn’t waned. Spooky folk singer Karen Dalton and S&M funkstress Betty Davis were both obscurities during their career peaks, whose albums, even in the ’70s, you couldn’t find anywhere. Thus there was an out-of-the-box urgency and demand for LITA’s reissues—the label’s purpose, essentially, was to make the public hip to astounding artists barely anyone had heard of. To do so, LITA beefed up the albums’ liner notes with in-depth essays, rare photos, and testimonials from heavies like Iggy Pop and Devendra Banhart.

Though Gainsbourg died in 1991, it could be argued that his legend needs no help from a little Seattle record label. As a 2008 New York Times article noted, the man’s groin-driven jams and “dirty old man” rep still inspires fashion designers, musicians, visual artists, and interior designers today—not to mention Gainsbourg, a French-themed Seattle bar (co-owned by SW music columnist Hannah Levin).

“It certainly presented a challenge to us,” says Sullivan of Gainsbourg’s established fame. “How are we going to market this and make this something definitive that people will to want to buy?”

For starters, LITA’s reissue is the first to print lyrics in both French and English. Now even more readers can follow Gainsbourg’s story of an old sleazeball who runs over a teenage girl with his Rolls-Royce, deflowers her at a fleabag hotel, and later foresees her plane crashing while she’s en route from Paris to London. And no reissue had ever elaborated on the album’s backstory, juicy though it is. In the thick liner-note booklet, LITA tells the Melody Nelson story with two beefy essays and an English translation of a rare 1971 interview from the magazine Rock&Folk in which Gainsbourg talks about the album in depth. (Quoth Gainsbourg: “I am incapable of mediocrity.”) And—DJs take note—LITA’s reissue is the first on vinyl, though the album’s been considered a break classic for decades.

From an indie-label standpoint, licensing an album from Universal is not hard. But it is a bit pricey (about $3 per CD), and allows for little marketing creativity. Sullivan says acquiring additional photos of Gainsbourg would have cost $1,000 a pop, so don’t look for any. Universal also won’t give up its licensing rights for TV, film, or digital media (iTunes). This means LITA can’t stream the album on its Web site or offer promotional mp3s or 7-inches. But that’s where Gainsbourg’s cemented fame works in their favor: LITA won’t have to work hard to make people care.

Though LITA is the first label to license Melody Nelson stateside, it’s long been available in U.S. stores. “There’s a French division of Universal, and they’ve had import versions available—you can go pick it up at Easy Street or wherever. But it was just in a jewel case and only had, like, a little eight-page booklet. It just didn’t feel very special.”

Sullivan’s sentiment highlights the very conundrum of music hustlers everywhere: In the era of downloads, how do you create something people will pay for if they can get it for free? LITA’s formula in the past has been to package albums that proclaim “You’ve never heard of this artist, but you should have, and here’s why.” With Melody Nelson, LITA is saying “Yeah, you’ve heard this story, but not all of it.” Again, why hadn’t anyone thought of that?

“I don’t know,” Sullivan reiterates. “But to have an album like this in our catalog is a dream.”