In 1996, some post-fun “sound collage” types decided to tear Beck to shreds by dis- and reassembling his catalog to make it sound like avant art-schmutz. The problem was that both the impetus and the title of their compilation were like carrying coals to Newcastle: Deconstructing Beck is essentially what the man’s been doing to himself since he bought his first pack of Duracells for his Tascam four-track. After 1994’s Mellow Gold became the most entertainingly inaccessible and fantastically batshit platinum album of the past decade or so (listened to “Sweet Sunshine” or “Mutherfuker” lately? They wound up in a million homes), cynics brushed him aside. Then he sanded off a few edges and turned into an Important Artist suddenly open to a bit of identity-eroding malleability. Watch him go like a droning Caetano Veloso on Mutations or beat himself black-and-blue with ’76 Jaggerisms on Midnite Vultures, unafraid to cry ’cause nobody told him he was a fool to; gape in perplexity as he sighs like Gordon Lightfoot all over Sea Change.

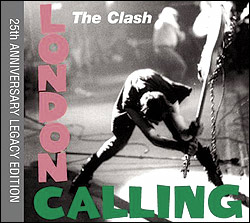

So what happens when a modular showbiz Zelig gets his wires crossed and self- consciously returns to the idea of making a Beck Album? Guero (Geffen), a likable, often excellent record on the surface (and crucial), strictly sound level that nevertheless feels off. The familiar ramshackle sheen of his mid-’90s exuberance is a welcome return at first, from the na-na yeah-yeah-yeah-yeah choruses to the tinny Atari melodies straight out of Homestar Runner. He also sounds great when the instrumentation is subtle and stripped-down; the microfunk “Black Tambourine” and the Jack Whitened thud-boogie lope of “Go It Alone” sound massive and close-quarters at the same time and glide with a deceptively laid-back nonchalance. And few things are as breathtaking in his catalog as “Earthquake Weather,” which distills a number of recognizable past- persona signifiers (Odelay scratches and loping Dust Brothers breaks, Mutations tropicalia guitar, Midnite Vultures falsetto), lays them out on a swap-meet table, and throws in an Ernie Isley–caliber guitar wail.

Mostly, though, Guero sounds like a collection of eight years’ worth of Beck outtakes. “Qué Onda Guero” is essentially a barrio-gawker “Hotwax” (from Odelay), while “Girl” gloms onto the casual-vandal Brian Wilson vibe of B-side/import standby “Electric Music and the Summer People,” with a dash of early Kinks (circa “David Watts”). “Rental Car” is essentially “The New Pollution” getting drunk with Mutations‘ hidden baroque-punk track, “Diamond Bollocks.” At least it’s not just another pretty downer, though: The Sea Change–ling “Broken Drum” and Mutations-ish “Missing” do little more than stand there, looking lonely and casting big, mopey rain clouds over the overachieving party tracks that surround them.

Some party, though. Beck is back to writing intriguing lyrics again, but they seem to be big on death and caulk the beat-poetry gaps Sea Change hewed with sour defeat and fleeing-car haggardness—”A void we filled with death,” to quote “Earthquake Weather.” Only two songs avoid mentioning death, firearms, or the devil; one of them, “Hell Yes,” is the most insidious in its efforts to get people dancing to a travelogue of debris (“Bank notes burn like broken equipment/Looking for shelter, readjust your position/Thought control, ghostwritten confessions/Two dimensions, dumb your head down”). It’s like Scorsese’s vision of Vegas in Casino, where the desert sits a stone’s throw from all the neon, dust blowing across recently dug graves.

I feel kind of dumb being put ill at ease by Beck songs, but it’s there from the opening lines: “Fourteen miles from a landfill grave”; “Black hearts in effigy”; “Walking to the other side with the devil trying to take my mind”; “Hey now, girl, what’s the matter with me?” (Good question.) Guero features his most relentlessly malevolent set of lyrics since Mellow Gold, and a debatable attempt to rekindle its devil-may-go-fuck-himself subversion, only there he had nothing to either prove or lose. Mellow Gold made swinging through the city on a wrecking ball or contending with meth-addict grizzly bear mutherfukers sound vividly illicit instead of achy and defeated—which, the more I think about it, sounds less like the minor letdown I halfway hear it as and more like his Steely Dan move, L.A. all the way.

But the way Guero jumbles Beck’s stylistic repertoire only underlines how tenuous his identity is. It’s easy to wonder how on the level the man can be considering that his upbringing was a mélange of Fluxus performance-art postmodernism and the clean-mind discipline of celebrity-caliber Scientology. (The recent revelation of this caused many to go “ewwww,” which makes me wonder if they’d be willing to part with their Isaac Hayes records, too; I’ll give ’em a tenner for the Truck Turner soundtrack.) The lack of a “there” here isn’t the biggest crime in music, especially from a Hollywood freak whose faux-naif hey-dude whimsy is more Owen Wilson than (his man) Gary Wilson and fits in nicely with the likably daft world of today’s multipurpose pop. But he solved the problem posed by his uncharacteristically flat last album too well: He remembered he was Beck. Then he started overacting.

Beck plays the Paramount Theatre with Le Tigre at 7:30 p.m. Fri., June 15. $37.50–$39.50.