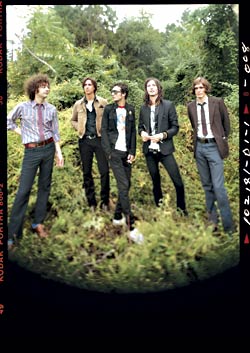

I never could see eye to eye with the Velvet Underground name-drops being thrown around early and often about the Strokes. “Last Nite,” my first exposure to them, sounded like Vespa rock for Jam fans, and Is This It and Room on Fire followed suit. Within their class, the subtly rudimentary Moe Tucker and the boisterous android Fab Moretti are exceptionally different drummers; singer-songwriter Julian Casablancas doesn’t have Lou Reed’s post-shock-therapy hush, and damned if I can find a John Cale in the bunch. (Happily enough, none of them seems ready to turn into Billy Yule, either.)

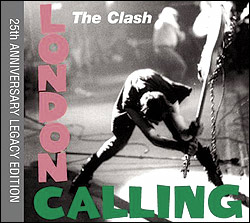

But it turns out that those VU references weren’t actually that far off. It’s just that the Strokes aren’t Andy Warhol’s Velvet Underground—they’re Andy Warhol. From the surface details of the new First Impressions of Earth (RCA)—the cover a shaky silk-screen reproduction of Steely Dan’s Aja, the trashy booklet artwork filled with retro-stylized appropriation, a song called (yes) “15 Minutes”—the Strokes are acting like pop artists in both senses of the term, refracting the iconography of American culture through the lens of consumerist media. In this case, the soup cans in question are shaggy hairdos and lyrics about mixed-up relationships, and a mumbling, wailing, often-aloof voice that caricaturizes the rock archetypes of the past two decades: Kurt Cobain as aspiring Bono.

“So that’s why I hate them!” goes the knee-jerk reply. But it runs a bit deeper than that—shallower, too. Post-’70s, rock’s self-recycling has flaunted a bit of entry-level self-awareness in its very existence, deliberate or otherwise. All the bafflement and backlash that came about when the Strokes were touted as early evidence that “rock is back” really brought to the table was the big idea of rock as a romanticized (and Ramone-ticized) and naggingly familiar cliché. The idea that rock was “back” mattered at least as much as the actual rock being made—not the most ideal situation for a skillful band of formalists who seemed as surprised by their figurehead status as the instant-backlash brigade were annoyed.

The Strokes’ resulting fatigue of expectations—exacerbated by the follow-up jitters that made Room on Fire a nerve-wracked rush job—is the driving force behind First Impressions of Earth. Like the title implies, there’s a certain self-conscious faux naïveté at work, and the album’s strengths originate from the Strokes’ deliberate attempts to goof on their unearned rep as a media fabrication, not to mention the entire idea of the Breakthrough Album. Right at its core is the band’s decision to jettison producer Gordon Raphael in favor of David Kahne, a man who (law requires I mention this) previously worked with Sugar Ray, Tony Bennett, and Cher.

As a result, everything in the album’s sound is cleaner, tighter, glossier, and more radio-friendly than before—a “sellout” move that doesn’t really compromise much of anything, from a band that’s long since alienated the types of people who worry about selling out in the first place. Other hallmarks of the third-album “we’re trying new things” tradition are omnipresent. There are strange, fascinating digressions from usually knowable guitarists—the Repo Man soundtrack punkabilly atmospherics of “Juicebox,” the Thurston Moore–isms that open “Ize of the World,” the epileptic Turkish surf-rock freak-out solo in “Vision of Division.” The minimalist chamber- orchestra synth of “Ask Me Anything” fulfills the requisite “break from type” experiment. There’s even an anticlimactic but likable album closer; the deceptively cheerful “Red Light” starts out with the same beat as the Minutemen’s “Nothing Indeed,” then turns into Queen.

To say their sound has changed significantly would be misleading—they still have that dog-fighting Nick Valensi/ Albert Hammond Jr. twin guitar exchange and a rhythm section that Blondie would envy. And they still have Julian Casablancas, probably the only man in rock who can sound resigned while screaming at the top of his lungs. In the midst of his usual pleas for better communication skills and less overall uptightness, he’s also managed to grow into a stealthily witty lyricist. A fair amount of it seems to stem from a reactionary yet lonely whatcha-want-from-me stance, vitriolic on paper and neurotic on CD, like Dustin Hoffman playing Travis Bickle. “I’m tired of everyone I know, of everyone I see/On the street and on TV/On the other side, on the other side, nobody’s waiting for me,” he laments on “On the Other Side.” “I hate them all/I hate myself for hating them/So I’ll drink some more/ I love them all/I’ll drink even more/I hate them even more than I did before.”

It’s a recurring issue, Casablancas’ not knowing what to do with or about anyone else, and the fear of artistic futility is mixed in liberally. “God is trying to talk to you/We could drag it out but that’s for other bands to do/I’ve got nothing to say,” he murmurs on “Ask Me Anything.” “Red Light” later reveals that there are 7 billion people pretty much in the same boat and “an entire generation of entertainers to blame.” And sometimes Casablancas blames himself, as on “Electricityscape,” the Strokes’ semi- analogue to “Don’t Believe the Hype”: “I swear I’ll give it back tomorrow/But for now I think that I’ll just borrow/All the words from that song/And all the chords from that other song I heard yesterday.” No, you can’t have your indie cred back, silly rabbit.

“We wanna sound like stuff from the future you’ve never heard before that references stuff from the past,” Casablancas told Billboard while in the studio constructing Earth, a statement simultaneously filled with rock-dude obviousness and reasonably clever Zen logic. We can give up trying to deduce a more detailed MO right now. Hell, it’s been almost 50 years since Warhol decided that recontextualized reproductions could be art. We shouldn’t be surprised when it makes for great rock albums, too.