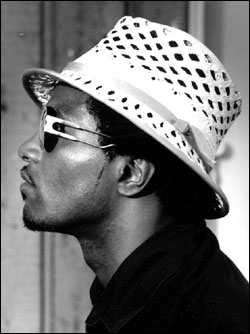

“It was cool, and I don’t mind talking about it, but . . . you know, a nigga always movin’ on to the next thing.” Ishmael Butler, once upon a time known as “Butterfly,” speaks in an easy, loping drawl only the unschooled would call lazy. Rather, Butler’s voice dips and rolls and swings from side to side as he talks about where the last 10 years have gone, what’s happened since his former band kick-started the acid-jazz resurgence, and what it all means today.

It’s a fair distance from Seattle to New York and back again, but Butler, who as a kid called the Emerald City home, is happy to be back. “After the New York thing, I felt like I wanted to come back, you know, be around my mom and my family and all that, get together with some new people.”

By “the New York thing,” Butler means a lot more than he’s saying. As one-third of early-’90s rap trio Digable Planets, he helped to spearhead a brand of hip-hop that reached back into bop and cool, and wedded acid-jazz loops to urban poetry. Before the Beastie Boys name-checked Lee Dorsey, before Blue Note records got wise and anthologized their tastiest acid nuggets on the Blue Break Beats series, Digable Planets were dropping coffeehouse/boho club science on releases like 1993’s platinum-selling Reachin’ (a new refutation of time and space) and the criminally overlooked Blowout Comb in 1994.

If all this sounds a shade dramatic from a contemporary standpoint, consider: First, this was concurrent with the rise of testosterone-soaked gangsta rap and celebrations of “thug life.” Digable Planets werebefore the Fugeesa two-man, one-woman combo that demonstrated there was no room in hip-hop for gender-dis bullshit. And though Butler takes pains not to slam other artists (“It’s not a hayride for these people. They work hard”), there’s no denying that Digable Planets were light-years ahead of contemporary hip-hop acts in their learned celebration and reconstruction of black musical history.

Second, Digable Planets cut the wax before the days of digital editing, which put the power to create the kind of music they were making in the hands of a much greater number of people. While that’s doubtless a very good thing from a certain standpoint, the fact that Digable Planets were among the last of the snip-and-loop rap acts tends to make them seem derriere-garde, when in fact they pointed the way for acts like Musiq Soulchild and Imani Coppola.

But, of course, there’s always the next thing.

THE NEXT THING is Cherrywine, a full- instrument band steeped in the traditions of funk, soul, and guitar rock. The project grows from Butler’s collaborations with several Seattle funk musicians, notably guitarist Thaddeus Turner and his brother, bassist Gerald Turner. Signed on merit to D.C.-area label DCide, Cherrywine enjoyed enough freedom during the recording to keep the sessions loose and intuitive.

“They heard some sketches in advance but not much in the way of finished music,” Butler says. “‘Just go on and do your thing, and if we like it, we’ll put it out,’ was basically what they said. And fortunately, they liked it.”

Cherrywine’s music, as presented on the just released Bright Black, represents Butler’s recent immersion in funka move prompted by the Turner brothers’ performances and consolidated through Butler’s own recent commitment to learning both guitar and keyboards. Bright Black bears strong ties to the smoky late-’60s sounds of Funkadelic and Sly Stone, but to call it a departure from hip-hop would be misleadingand Butler, in any case, has yet to create a “pure” record of any sort.

“A lot of people, and it’s kind of surprising where you see it, have a very conservative approach to hip-hop, wanting it to stay like it was forever, and not wanting a brother to progress. It’s like, ‘Well, why ain’t you with your high-school girlfriend no more? Y’all were good together. You went to the prom.’ But the whole historic black pimp/hustler idea was to set yourself apart from the crowd, you know? When I was coming up, you could go and see Kid ‘n’ Play open up for Big Daddy Kane or N.W.A.it wasn’t about who sounded like who.”

Thus Cherrywine’s forte is to merge hip-hop’s driving percussion with funk’s loose, languid guitar lines and jittery keys. At their besttake Butler’s whip-crack delivery on “Mr. Anchorman,” a tale of infidelity and backpedaling set over a nervous minor-chord progressionCherrywine manage to balance a smoldering eroticism with brooding character exploration. (Bright Black is, at least thus far, the thinking fan’s album of 2003.)

Or take “Dazzlement,” a vivisection of gangster mythos and music that manages to serve up the last decade of mainstream hip-hop, while somehow reserving one unironic, good-natured swagger for Butler himself (“I was so flyyyy . . . ,” runs the insistent tagline). Stupidly read by a capsule “reviewer” in FHM‘s April issue as straightforward thug-wanna-be bashing, “Dazzlement” actually distills the thing Butler and Cherrywine do bestmine and rework the contemporary history of black music, then manage to make something both new and traditionalist of it.

“I think about those early days of hip-hop a lot,” he says. “Those days were a lot less materialistic, you know, and it was about showing your style. People talk about the difference between Cherrywine and Digable Planets, but I really don’t see it. I just see it as a natural progression.

“Or, if you will: Like everybody else, I wore different clothes five years ago. These are the clothes I’m wearing now.”