PICK UP ANY ARTICLE on “The Death of Classical Music” and see if it talks about anything other than the financial performance of professional orchestras in mid-sized North American cities. Oh, it might mention in passing the turmoil in the classical record industry (the main cause of which is greedy labels), but that’s merely presented as evidence in a damning front-page case. Those collapsing ensembles in, say, Calgary, San Jose, or Savannah are the canaries in the coal mine foretelling the collapseany day now!of the 1,000-year-old art form.

Let’s read a little further. There are other indicators of classical music’s health. What about opera attendanceup, by all accountsor that of chamber music, choral music, and new music? Or take a look at a particularly telling phenomenon, a region’s community orchestras, staffed with people who realize that classical music doesn’t have to be just a spectator sport. Greater Seattle’s peculiarly blessed in this regard.

George Shangrow’s variable-sized Orchestra Seattle reflects his eclectic tastes: He’ll program lots of small-ensemble baroque music (Orchestra Seattle is probably the most early-music-oriented of our community orchestras), then turn around and muster vast forces for works like a Rachmaninoff concerto or Ravel’s Bolero. With the Seattle Chamber Singers, Orchestra Seattle is doing four evening-length oratorios this season. Upcoming season highlight: Carol Sams’ The Earthmakers (Feb. 15). Contemporary music score: Out of 17 works on this season’s concerts, two are by living composers.

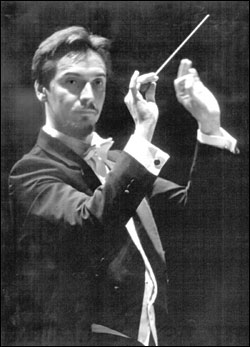

The Tacoma-based Northwest Sinfonietta is an excellent chamber orchestra that might prefer to be called a professional rather than a community group. (What’s the difference? Salaries, mainly.) The Sinfonietta’s playing four pairs of concerts (including one at Town Hall) and opened its season Oct. 3 with an all-Beethoven program. Christophe Chagnard led them with 鬡n through the Seventh Symphony, getting the dotted rhythms in the first movementa stumbling block for even the greatest orchestras almost completely right. Upcoming season highlight: an all-American concert (Copland, Ellington, et al., Jan. 30). Contemporary music score: one living composer out of 14 works.

Chagnard’s other ensemble, the Lake Union Civic Orchestra, assembled the largest group ever to play Town Hall72 playersfor its Oct. 24 performance of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique. The group also attracted the largest audience I’ve ever seen for a classical event in Town Hall, perhaps because of its fund-raising mission for health care organizations. It’s an awfully good orchestra; Chagnard pushed it through reckless tempos in the Berlioz, and the results were breathtaking. I thought the work’s last 20 orgiastic seconds might restore some of the cracks in Town Hall’s plaster (finally repaired after the February 2001 earthquake). Was it a perfectly tidy performance, every hair in place? No, but Berlioz isn’t an every- hair-in-place kind of composer. Upcoming season highlight: Carl Nielsen’s Inextinguishable Symphony (April 23). Contemporary music score: nine works, no living composers.

Roupen Shakarian’s always preferred a big beefy sound for his 40-member Philharmonia Northwest, keeping the winds, brass, and percussion prominent. For fast movements, he favors gentle tempos; his performances are buoyant, never stodgy. This made for a majestic, church- filling sound (at St. Stephen’s Episcopal) during the Oct. 19 performance of Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony. If the intricate counterpoint in the finale lacked a little definition, the overall sonic power provided a thrill. Shakarian asks his string players for a pure, clean tone and discourages vibrato; without this “fudge factor,” unity of intonation becomes an even greater challenge, but his well-trained strings manage impressively. Upcoming season highlight: Carl Reinecke’s meltingly nostalgic 1908 Flute Concerto (Feb. 8). Contemporary music score: one living composer out of 15 works.

That most adorable of masterpieces, Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, closed the Oct. 26 concert by Seattle’s largest and oldest community orchestra, the Seattle Philharmonic. Full of show-offy solos for everyone, the Guide was a risky choice for a season-opening concert. Then again, for just that reason, it’s a great training piece. The strings, especially, sounded a bit out of focus in exposed passages, but new music director Adam Stern clearly intends to rectify that. Upcoming season highlight: a Concerto for Orchestra by Goffredo Petrassi; born in 1904, he died last March, so this will be both a memorial and a centennial observance (Jan. 25). Contemporary music score: 18 works, no living composers (well, Petrassi almost made it).

Significantly, these five orchestras are attracting not merely sizable audiences, but enthusiastic and convivial ones as welllots of families who came to hear Mom play oboe. And there are a half-dozen more like them. It’s a heartening indication of the liveliness of Seattle’s classical scene, which a look at the bottom lineor headlinesdoesn’t reveal.