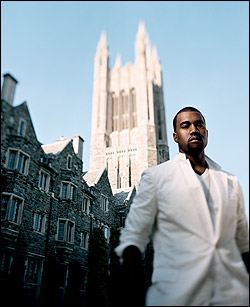

Kanye West is a race man. The College Dropout began with “We Don’t Care,” part singsong shout-out to “all my peoples who’s drug dealing just to get by,” part playground taunt directed at the conspiratorial powers that be: “We wasn’t s’posed to make it past 25/Joke’s on you we still alive.” His follow-up, Late Registration (Roc-a-Fella), leads with the more desperate “Heard ‘Em Say,” a survey of soul-eroding ghetto scourges typically not glamorous enough to blip across the megaplatinum rap radar: not crack but cigarettes, not the difficulties of pimping but the pitifully low rate of the minimum wage, not conspicuous consumption but that regressive tax system known as the lottery.

Given this evidence, West’s impolitic blindsiding of Mike Myers on live TV should have been less startling. Yet in all the talk about Kanye West, Conscious-Rap Anti-Gangsta Genius, his racial solidarity has often been lost amidst the pink pullovers and nerdish post-Puffy flow. Celebrations of mass negritude are expected to issue forth from someone less socially acceptable, someone edgier—someone, you know, blacker. But in the world of big-money hip-hop, that’s just not happening. The thug rap that once laid a claim—spurious maybe, but insistent—to righteous rebellion now lolls in a nouveau-riche stupor, too lazy to even play the race card. Maybe the ghetto paranoia West resurrects on “Crack Music”—”How you stop the Black Panthers?/Ronald Reagan cooked up an answer”—is so shopworn that Chuck D flows like Manning Marable by comparison. But the harsh deliberation with which West rhymes its title with “black music” drives home its metaphorical truths.

In a less morally ambiguous time, West would be easily dismissed: as a hypocrite, a demagogue, an opportunist. Sure, “Diamonds From Sierra Leone” is where one of the few stars to front political onstage at Live8—slamming bigwigs “riding home in their Benzes and Bentleys while poor Africans starve”—notices the black-on-black crime that makes Freetown a hood no G-Unit member could likely survive. It’s also—OK, primarily—about how West loves to floss. And good luck detecting conscious irony in the way West floats his purely self- celebratory “Touch the Sky” on the community-minded buoyancy of the Impressions’ “Move on Up.” At the very least, his lyrics seem aware of the intractable question with which black intellectuals have historically struggled—how can the black community thrive amidst laissez-faire capitalism? Celebrity hip-hop prefers to sidestep it, pretending individual triumph compensates for past injustice. “Overchargin’ niggas for what they did to the Cold Crush” as Jay-Z once put it, and I hope Grandmaster Caz didn’t piss away too many hours by the mailbox waiting on that check. Translation: Jay’s not a race man, he’s a race, man.

Given the fact that Jigga skedaddled from a hip-hop scene he deemed “corny,” rather than risk his rep by taking an artistic chance, Kanye’s broad-mindedness alone sets him apart as a bona fide culture hero. For starters, his definition of “black music” doesn’t preclude orchestral help from the don of L.A. baroque singer- songwriter pop, Jon Brion. The two collaborators whip up an opulent setting that parallels the lushness of ’70s post-soul as envisioned by Norman Whitfield or Gamble and Huff without replicating it. Grime and elegance coexist; the contrast between a graceful piano plink and an impossibly low bass smudge nudges “Heard ‘Em Say” in the spiritual direction of Stevie Wonder, with Adam Levine of Maroon 5 cutting 99 percent of the nasal squelching emitted by would-be Jodeci II auditionees over the past decade. But when West wants to flaunt his commitment to rhythm, as on the gutbucket “Gold Digger,” he gets black and proud again. The song assumes the worst about men and women: Devious vixens will siphon child support from millionaires to pay for liposuction; ambitious nobodies will “leave your ass for a white girl” once they make it big. But throughout Ray Charles yelps, “She gives me money,” over the beat, as though to say: Men and women have been picking each other’s pockets for years, shit ain’t nothing new.

Another sampled soul great puts a defining mark on the finale, “Gone.” Otis Redding is the quintessential voice of joy weathered by memories of pain, but his let-it-rip fearlessness has occasionally been slighted by soul snobs who prefer Solomon Burke’s masterful contrast between restraint and release. Similarly, West’s real gift, his unpolished delivery of half-rhymes and incomplete puns, is lost on heads who think rapping is a matter of technique. West may never quite match Redding’s untrammeled good will—few have—which is why his exuberance is still occasionally misread as arrogance. But he shares a sense of indomitable scrappiness, a connection to history that insists that just as those in the past made their way in the world—with humor and tenacity—so will he. Have you heard the one about the cultural contradictions of late capitalism? Kanye West is happy to be its punch line.

Kanye West plays Everett Event Center, 2000 Hewitt Ave., Everett, 866-332-8499, with Fantasia and Keyshia Cole at 8 p.m. Sat., Dec. 10. $33–$43.