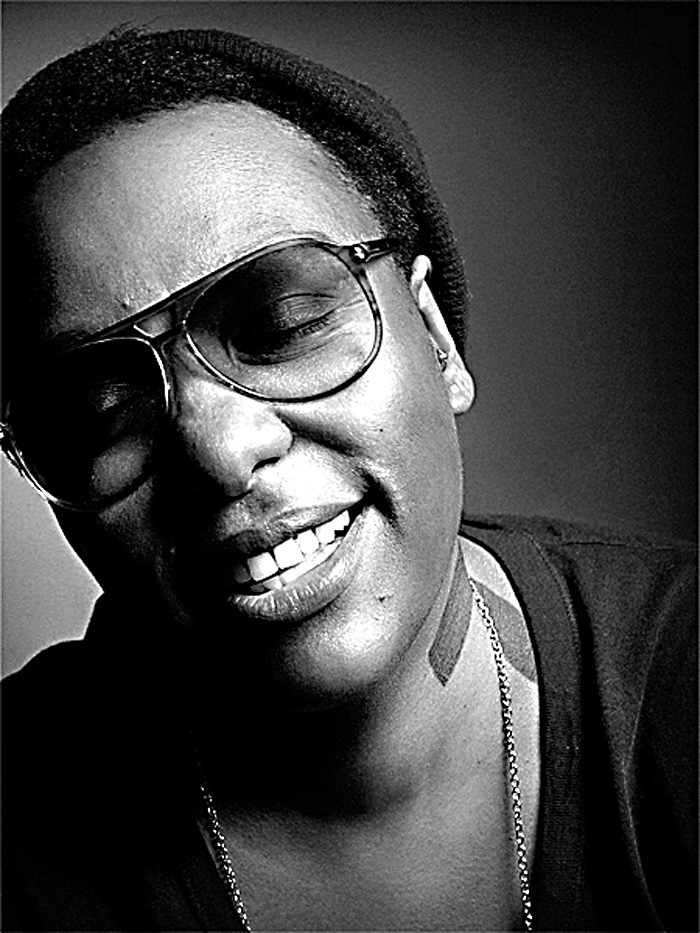

With her brand new album, Vagarosa, Brazilian singer/songwriter Céu lends new meaning to the term “sophomore slump.” The follow-up to Céu’s 2005 self-titled debut, Vagarosa–which translates as “slow, leisurely . . . one who doesn’t hurry”–was expressly crafted to ease pressure: not just the pressure that came with Céu’s immediate success in Brazil and the U.S., but yours as well. As the title conveys, Céu wanted to slow down, take it easy, remember to live a little. And she wants listeners to do the same.

“After all the shows and activity for the first album,” she explains, “I wanted to return to something that’s essential in music to me, which is silence. It might seem strange to say it, but silence is important for music, the whole idea of being quiet in your life and staying present in the things that you do. Because everything today is so fast. Everybody has so much to do and a lot of information to take in. Sometimes you’re doing something, but you’re not exactly doing that thing, you know? Your mind is traveling around.”

Céu explains that in spite of modernization, Brazilians, much like Latinos across the board, have managed to “preserve the importance of relationships.” People still tend to make time for one another. But São Paulo—the chaotic, bustling, overwhelmingly large city where Céu was born and continues to live and record—is a different matter altogether. Céu chuckles when she describes her relationship with that city as “love-hate.”

“In São Paulo,” she says, “a huge place with the same vibe of any megalopolis around the world, everyone is so alone, even though they’re in such close quarters.”

Given her perspective, it’s fitting that Céu (pronounced like a cross between “say-oh” and “cell”) now stands a chance to reach a wider audience in the States, a place where hustling from one scheduled appointment to the next is a culturally engrained way of life. Despite the language barrier, most American listeners should have no difficulty relating to the point that Céu is trying to communicate. Vagarosa, released July 7, will hopefully hit our shores as nothing less than a wave of much-needed relief for those who end up taking the time to literally sit with it. Sure, many genres—ambient, jazz, and Brazil’s own bossa nova—are rife with examples of calm, sedating music, but rarely has laziness as a goal been captured in such an artful fashion.

Céu (whose full name is Maria do Céu Whitaker Poças) has, with the help of her production team, managed to put some rather fresh Brazilian twists on familiar genres. Discreet sprinklings of electronica, soul, hip-hop, and jazz flow by in a gentle stream of down-tempo samba rhythms.

It’s tempting (and perhaps too easy) to look at Céu’s work as a kind of Latin answer to Morcheeba. The listener barely notices as Céu adroitly shifts gears from song to song, the body perhaps more relaxed with each graceful sway into a new combination of styles. On “Cangote,” for instance, a lounge-organ figure, classic-jazz horns, and a dub bass line all brush elbows with utmost ease. And that’s just one example. With each successive tune, Céu starts from scratch with a new recipe, her gliding voice the one constant.

Céu’s blossoming proficiency at genre-dabbling can be traced to a breakthrough while visiting New York City at 18. As Céu, now 29, explains, it was then that she got over her inhibiting reverence for Brazilian musical tradition. At that age, she was already “crazy about” Jamaican styles and afrobeat, but landmark albums by Erykah Badu, Lauryn Hill, and D’Angelo had an eye-opening effect on her. Being that far from home had two profound benefits for her creativity: it made her homesick enough to start writing, and it gave her just the right amount of distance from her native Brazilian music to realize how deeply she had always had it in her to capture it with her own original material. Meanwhile, New York’s ever-vibrant underground street culture helped Céu shed her inhibitions.

“My family was so tough on musical education,” says Céu. “My father’s a music teacher, and I just couldn’t imagine myself doing my own music. Until that trip, for me to compose was something really difficult. Songwriting was only supposed to be for geniuses, not for some girl who wanted to make her own melodies but was a bad composer. New York was nice because I saw that you can just do it. Music is something that’s free. There’s no problem if you just try something.”

All the while, regardless of how rebellious or adventurous she was feeling, Céu never lost her love of the music of her parents’ generation. For Brazilian youth, however progressive their musical tastes may be, the influence of traditions like samba and bossa nova remain all but unavoidable. Unsurprisingly, Céu grew up listening to seminal samba and bossa nova luminaries like João Gilberto, Nelson Cavaquinho, and Cartola. But even when she was making a concerted effort to broaden her horizons, she wasn’t distancing herself from the music of her homeland, but instead trying to expand its parameters. Perhaps that accounts for why Céu’s work flows so smoothly.

“That old music is something that I can’t deny,” she says. “Sure, when you’re growing up, you start to like other things. And sometimes people don’t understand that a young Brazilian girl can mix Jamaican music with traditional music. But you just naturally end up mixing new influences with the things that are in your DNA.”

Whatever she’s doing, it’s working. Céu has already achieved celebrity in her homeland, and Starbucks distribution has helped propel her to Grammy nominations on both continents. But for Vagarosa, Céu did her best not to think about all the attention she’d gotten the first time around.

“I just tried to tell new stories,” she says.