When I consider the act of moving out of the U.S., I always think of Keguro Macharia’s words in his essay “On Quitting,” about his resignation from the American academic system to move to Kenya. “Perhaps it will provide a space within which scabbing can begin, and, eventually, scars that will remain tender for way too long.”

For those with a troubled relationship with this country, the fantasy of moving away is not uncommon—a fantasy that erupted into reality after the election finale when Canada’s immigration website crashed. For immigrants and people of color, for whom America’s hostility manifests in the jingoist’s taunt “Go back to your country,” sometimes the most enticing retort is, “That’s a great idea.”

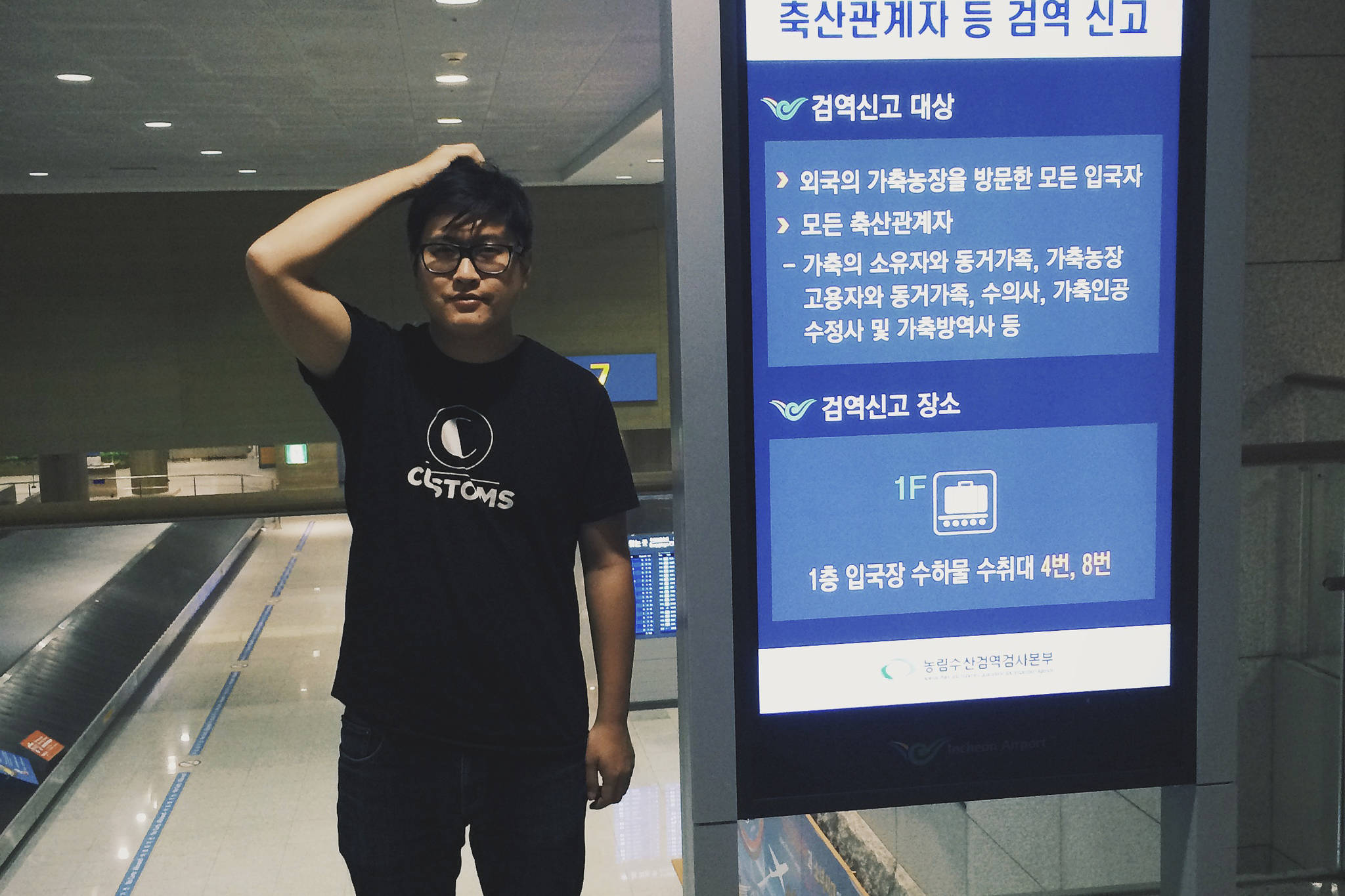

Allen Huang, for one, is moving to Taipei. Born 33 years ago in Capitol Hill, Huang is very integrated in Seattle’s music scene and has been active as a promoter for the past three and a half years. The promotion collective Customs that Huang organizes, along with Alex Osuch, Reed Juenger, Denise Zhang, Alex Ruder and Ben Chaykin, has booked nearly 50 shows, including Detroit-based footwork legend RP Boo, Japanese juke musician Foodman, and vaporwave forerunner Ramona Xavier’s project Vektroid, to name just a few. The genres are varied, but Huang says one of his main focuses is celebrating Asian and Asian-American artists, such as Metome and Seiho from Osaka, and Mark Redito from Los Angeles by way of the Philippines.

After years of consideration, Huang finally bought a one-way ticket to Taiwan. “Living here has been calcifying a bit, and I think my needs need more room to grow. It kind of feels like a break-up.” He jokingly adds, “We need to see other worldviews.”

Some relationships you stay in past their expiration date because you think they’re the glasses that you need to make the world seem clear. Some are so transformative that leaving them would be like leaving yourself. Yes, comparing your relationship with a nation to one with a person has its limits—perhaps the biggest being that unlike a person, a nation like the U.S. has its reaches all over the globe. You can leave its soil, but you won’t leave its grasp. Although Huang’s family is from Taiwan and he has Chinese heritage, he is moving to Taipei as an American. As we talk, Huang expresses unease about perpetuating negative expatriate (“expat”) dynamics in Taipei, as Taipei now ranks as one of the top 10 destinations for mainly Western and white impermanent residents, who come to teach English or work in English-speaking sectors. Especially in emerging cultural scenes, expats can have a strong influence in determining the taste and values for base populations that have been less exposed to global music trends.

“Taiwan’s electronic music scene has been growing a lot in the past decade,” Huang says. “It’s a burgeoning scene, and people are excited for more. I don’t want to just do the same things I’ve been doing in a ‘more starved area’ and feel good about that. I don’t want to come in and tell people what to do.”

Aside from occupying positions as cultural tastemakers, expats also make up a sizeable portion of the audience for events. “I don’t want to get into the trap of doing shows just for expats,” Huang says. “I’d like to take steps to broadcast to a Taiwanese audience. That’s why I want to work with people over there, rather than compete with them.” Huang plans to get involved with local creative projects such as Under U, a Taiwanese booking collective that recently brought in London electronic musician Faze Miyake. Huang’s ability to speak Mandarin will also allow him to bridge one barrier—the one between residents who speak and don’t speak the local language.

The poet Ocean Vuong was renamed Ocean by his mother, as an act of independence after she divorced his father. She named him after the Pacific Ocean between Vietnam and the United States, evoking the image of a spirit suspended above the sea between two landmasses. “Like that expansive stretch of water, I touch both nations but belong solely to neither,” he said in an interview in 2013. This line pinpoints how it feels to be hyphenated, partially tethered to two nations with different, even clashing values. I asked Huang if he expects to feel more connected to the locals in Taiwan than he does to Asian Americans here. “I’ll always be an Asian American,” Huang reflects. “It’s always going to be different between me and someone who was born in Taiwan. I’m looking forward to the cultural differences.”

How may the distance between Asians and Asian Americans be felt? “Asian American” is a reference with a specific lineage: In the 1960s, spurred by historian and activist Yuji Ichioka, people began to self-define as “Asian American” to challenge the mainstream pejorative term “Oriental.” More than a semantic issue, the Asian-American movement was largely inspired by the Black Power movement to mobilize to exercise political power and build solidarity with other communities of color. As Asian Americans and people of color, we’ve had to consider what membership to these categories means on this country’s soil—categories that are useful and mobilizing at times, and burdensome and oversimplifying at others. In “On Quitting,” Macharia writes about developing “a growing, all-encompassing inability to engage with anyone without my racialized armor on,” and shares that “encounters seem too weighed down by history.”

It’s a hard reality to confront when you move away in an attempt to re-integrate into your homeland and find that you couldn’t flee from the American embedded in your personhood. This is what environmental educator Kriss Harper experienced when she attempted to live in Ghana. “I lived in Ghana for four months—had an identity crisis. I am hella Americanized, and Ghana was not home. Seattle is home.”

Even when you don’t feel a sense of belonging in the U.S., leaving is not an option for some. “I think about it all the time,” artist and Seattle Weekly contributor Sofia Lee says of moving out of the country, “but in my personal case, I am queer, and that has already strained the relationship I have with my American family. I can’t imagine having to go through that again with distant family in a new country and hav[ing] even more of a language and culture barrier at the same time. Ultimately, I’ve concluded that the best case I have for myself is to find somewhere in this country with a lot of Chinese immigrants and live there and help build that community.”

Moving away is never only about where you put your body—if you’re lucky, the place you find to call home can be a nurturing space for processing through the psychic injuries you accumulate from being alive. Some injuries are more abstract than others or can be traced back to worldwide injustice and cruelty, and they can cut so deeply that scars are guaranteed. While leaving this country is non-viable to some and unattractive to others, Huang views it as an act of repair. “It doesn’t feel like I’m getting a new lens of perspective as much as it feels like I’m getting LASIK eye surgery,” he joked. Sometimes the wounds can’t be remedied, but any way we can find to mend, even if it means uprooting ourselves entirely, seems worth a try.

Customs “Goodbye” Show, The Crocodile, 2200 2nd Ave, thecrocodile.com. $5. 21 and over. 8 p.m.

arts@seattleweekly.com