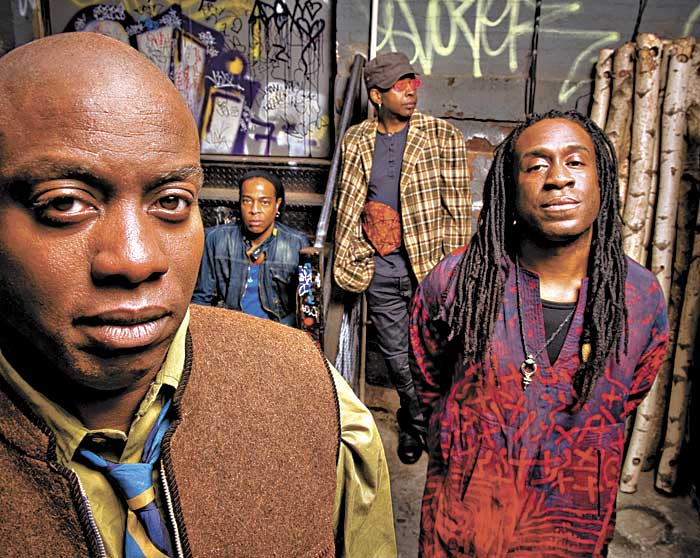

More than 25 years after Vernon Reid founded one of the most successful black rock groups of all time, much of his life remains unchanged. He still lives in New York, still maintains his long locks, and still shreds on the electric guitar. He’s also still more verbose than he needs to be. No matter what you ask him, he’s likely to respond with a 10-minute discourse on politics, philosophy, and human existence, jumping from one hard-to-follow example to another.

A diatribe that begins with ruminations on Chinese Democracy, for example, somehow concludes like this: “Our society is consumptive and hungry to be put on, to have ‘that thing.’ In many ways it’s a terrible society, the way we snort and eat people alive for sticking their head out.”

Of course, Living Colour has seen some changes. The group no longer fills arenas, but they’re also no longer plagued by the constant infighting that made so much of their history so tumultuous. After the multiplatinum success of 1988’s Vivid and a Grammy for “Cult of Personality,” they couldn’t maintain their success and were eventually dropped by Epic Records. This led to animosity and a pair of long hiatuses, the first of which inspired an intense period of introspection for Reid.

“I came up with this line—’Toss my keys in the river so I can’t go home again’—after the band broke up in the ’90s,” he says. “It just haunted me. It was a very hard, bitter time. We were friends, and it just was not working.”

The lyric made it into “Burned Bridges,” the first track on the band’s latest album, The Chair in the Doorway, an imperfect but engaging work full of their trademark funk-driven bass lines and pop-metal guitar-god riffs. The song focuses on the theme of self-destruction, and he and lead singer Corey Glover brainstormed it while camping out in a small Czech Republic town. “There was no general store to go, there was no escape from each other,” Reid remembers. “I said the line, and Corey just jumped right on it. It’s one of the first solid collaborations we’ve done since ‘Never Satisfied’ on Stain.”

The Chair in the Doorway was primarily recorded just outside of Prague, and obstacles to group unity became a major theme. Reid says its title refers metaphorically to the mental block, i.e., the chair, that inhibits the group members from getting along, i.e., walking through the doorway. Of course, this is only one of Reid’s interpretations; he also contends the song concerns people who play-act their existences rather than being who they really are. “Underneath their roles,” he explains, “[people] are quivering masses of protoplasm. That’s what the song’s about, the notion of escape.”

Make no mistake, Reid can be quite entertaining in conversation, particularly when he’s recounting stories of his group’s glory days. Shortly before playing a Los Angeles show with Guns N’ Roses in 1989, for example, Reid publicly called out Axl Rose for the racist, homophobic lyrics in their song “One in a Million”—a pretty ballsy move. Reid says he has no regrets. “Part of it was not like, ‘Man, you’re a racist,’ it was my disappointment that I’m a GN’R fan. I love Appetite for Destruction. I went out and bought it myself. I was very disappointed in him. It was like, ‘You assume you have no black fans!'” Reid adds that GN’R’s Chinese Democracy debacle shows that money and power can’t buy happiness. (At about this point, he segues into his digression about snorting people.)

He also defends the lyrics of Living Colour’s “Glamour Boys” (“Glamour boys swear they are a diva,” etc.), also long accused of bearing a homophobic message. “I can categorically say that that was never a part of the song,” Reid asserts. “In a weird way, in ’80s New York club culture, people were literally butt-up-against each other. If you meet somebody who’s working in a shop and they’re being nasty or weird because they’re privileged to work in this shop, then it’s interesting to have a conversation about that. There are heterosexual glamour boys and homosexual glamour boys.”

Perhaps there are. In any case, though in their heyday primarily concerned with politics, Living Colour’s members now seem more interested in exorcising their band’s demons. While this artistic stance is less likely to generate headlines, it seems to have created a healthy, productive working environment. If the songs on The Chair in the Doorway are any indication, the musicians appear finally to have made their peace.