Few writerly songsmiths—few of the decent ones anyway—ration their cleverness quite as stingily as Rhett Miller. Dude’s shown his aptitude for the pithy line since the early days of “Victoria Lee” (who “started off on Percodan and ended up with me”), yet the Old 97’s latest disc, Drag It Up (New West), isn’t the first time he’s used his lyrics to trawl for cringes. Take “Life comes apart at the seams it seems.” Please. Before he repeats it on the next chorus of “Borrowed Bride.” Miller’s not just bobbling language here, he’s chucking the ball over the first baseman’s head into the stands. If punning is the lowest form of humor, then it isn’t just misguided to place two similar sounding words side by side and expect them to spontaneously breed higher metaphoric beings. More like flat out indolence.

Yeah? Well pfffllllt to you too. Punphobia is for desiccated schoolmarms, distrust of the aural delights of language an affliction of puritans who’ll never forgive words for sounding like something before they mean anything. Miller doesn’t draw undue attention to “seams it seems,” just allows its sibilance to ring in the air as a lovely way to end a line. He’s pretty canny about using sound to establish mood as well—when, later on the album, another Miller paramour drives “a blue car around Bloomington,” the airy repetition flows fittingly into the playful setup, “She was a thin girl but she had substance,” and its zingy rhyme, “Most girls who live in Bloomington only come there to find husbands.”

The war over whether bad poetry can make for good rock lyrics was won years past, but there’s still fighting in the streets over that assertion’s corollaries; some of us won’t stop throwing rocks till it’s accepted that rock lyrics are sometimes good because they’re bad poetry. Now, no one would be so irresponsible to say that about just any bad poetry—we have a new Interpol album for that, thanks. But the deliberate awkwardness that hobbles written verse can renew language—just the way they always say good poetry ought—when sung warily.

Especially when, as Miller has for most of his career, you traffic in self-consciously gawky come-ons. His nearest analog verbally, Paul Westerberg, used to get away with such calculated offhandedness by suggesting he could have been smoother if he’d ever have felt like being bothered. Miller compensates by acting as though effort has never been a consideration, as though he wouldn’t know how to try if he had to, as though he’ll never have to. Where Westerberg punned out of desperation, Miller’s lines are posed as mere formalities designed to postpone another inevitable night of hot yet emotionally unrewarding sex.

Westerberg needed the momentum of the Replacements in order to feign spontaneity; Miller needs the 97’s to justify his well-honed casualness—as proven by The Instigator, the perfectly adequate (adequately perfect?) solo album L.A. producer Jon Brion groomed for him in 2002. Anyone who’s adjusted to the band’s stylistic changes over the years, from alt-country kitshickers to jangling shufflers to full on power-poppers, better get ready to head back to square one—the first roadhouse lick with which guitarist Ken Bethea lashes into “Won’t Be Home,” establishes Drag It Up as the sound of three other musicians reminding those fans who granted Miller exclusive auteurship that the Old 97’s are a band, and a roots-first band at that. Any doubts about who’s the auteur here, however, are cleared up by bassist Murry Hammond’s “Smokers” and especially Bethea’s “Coahulia”—no matter how many good licks (and OK lines) the guitarist gets off, he’s forbidden to approach the mike again until he demonstrates an ability to distinguish between Doug Sahm and Weird Al.

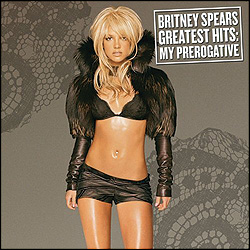

Still, Miller has adjusted his lyrics to the deliberately conventional constrictions the band has taken on; he’s apparently abandoned his quest to convince the world that great cheekbones don’t ensure happiness in love—that, in fact, they ensure quite the opposite—and to instead craft miniature reveries of lost love. So of course he traffics in borrowed nature tropes, both successfully (“Moonlight” reminds him of a lost love) and no (“Blinding Sheets of Rain” obscure the truth). Aesthete though he may be, though, Miller has a need for verbal looseness that chafes against the demands of formalism: The R. Kelly pun that opens “Adelaide” (“Heaven I need a drug”) may be strong, but the parallel constructions on successive verses (“need a rest,” “need a drink”) sound forced.

Still, “Adelaide” is astoundingly pretty, and formal design is a better target for Miller’s maturing ambition than the art-poesy of “Valium Waltz.” But it’s no mistake that the two best songs here are about getting older. “The New Kid” is bitterer than the Eagles song that it rewrites less than its title suggests; rather than smugly shrugging like fatalist twat Glenn Frey, Miller rages against the dying of the light. “Friends Forever” is a happier ending to the story of a “brain whose brain would never let up” that grew up to become a butterfly with great cheekbones who had lots of awesome sex and pined over his broken heart romantically ever after. “The moral of this song/Is that the high school kids are wrong,” Miller explains. And the moral of this album is that a craftsman’s display of wit is best expended on a concrete subject close to his heart.

Old 97’s play the Showbox with Jon Rauhouse and Christy McWilson at 8 p.m. $16 adv./$18.