The thing to do when heading into Seattle’s Lesbian & Gay Film Festival (beginning Fri., Oct. 15; 206-325-6500 or www.seattlequeerfilm.org for a full schedule)—hell, the thing to do when heading into Seattle’s lesbian and gay population—is to try not to get too sidetracked by the hotties.

One look at the offerings in the annual weeklong event will prove that, yet again, the festival knows on which side its bread is buttered—or, rather, how to make plenty of bread out of naked butts. Don’t play innocent, but choose carefully and don’t always expect the cheap eroticism to be all that erotic. On the Couch, a languid “behind-the-scenes” look at photographer Tom Bianchi’s soft-core oeuvre, features delicious gay boys taking it all off and touching themselves and, damn, it kind of bored me, er, stiff. Distaff patrons are dutifully offered their own escape with Hearts Cracked Open: Tantra For Women Who Love Women, but, come on, nobody expected me to sit through that, did they?

The lesbians I did take to heart are featured in Tying the Knot, a documentary about the fight for gay marriage that is as stirring a call to action as anything you’ll see on the subject (it’ll open for a regular run locally in the next few weeks). Jim de Seve’s film calmly refutes all the arguments from the right, but pulls most of its power from its focus on the disgraceful heartbreak caused by the government’s refusal to recognize homosexual unions. The devotion of Mickie and Lois, longtime policewomen who had been together for 10 years when Lois was killed in the line of duty, gets no respect when Mickie is denied her partner’s pension. Sam, an old Oklahoman who built a quiet life and raised three kids with lover Earl for more than 22 years, sees his farm legally seized by random relatives upon Earl’s death (and he’s then charged back rent!). If such stories don’t make an activist of you, nothing will.

Equally empowering, but a great deal more joyous, is the return of Harold’s Home Movies, a favorite from the 2001 fest. A compendium of silent Super 8 and other personal footage, it features several decades from the life of 94-year-old Harold O’Neal, and is a glimpse into the kind of unrestrained homosexual happiness and camaraderie that people would have you believe never existed before Stonewall—convivial house parties, playful group escapades on river trips, etc. For this latest screening, producers Jason Plourde (the festival’s programming director) and Sean David West went back to O’Neal and his longtime partner George Torgerson to record their reminiscences as narration for what is an intensely moving and necessary document of queer history. O’Neal’s death this past June makes the experience even more bittersweet.

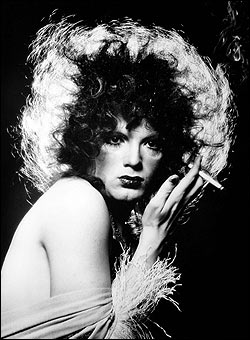

Another life receiving salute is Jackie Curtis, the Warhol Factory Superstar in a Housedress. Curtis, along with Candy Darling and Holly Woodlawn, made gender-bending cutting edge in the dizzying late ’60s and early ’70s performance scene in New York City. Craig B. Highber- ger’s documentary collects movie (Women in Revolt) and video clips (great snippets from Curtis’ gonzo, druggy drag extravaganzas), as well as terrifically funny, revealing remembrances from Lily Tomlin, Harvey Fierstein, and an epic parade of kooks and characters who’d be worthy of their own cinematic tributes (including the ever-bravura Woodlawn, always worth a look). Like Curtis himself, who lived madly and died of a drug overdose in 1985, the film has problems recognizing when it’s too much of a good thing—it’s virtually shapeless, and you can forget about pacing—but it successfully demands your allegiance.

Other picks? The rare chance to see the iconic Rebel Without a Cause on the Cinerama screen is too good to pass up, and Dorian Blues, the closing night selection also at the Cinerama, is surprisingly charming. Debut writer/director Tennyson Bardwell isn’t doing anything more than telling yet another coming-out story, but the result is so personal and casually affecting it catches you off guard. “I have a good heart,” Dorian (Michael Millan), struggling with his sexual identity, tells his therapist, and he’s right: Millan, dry-witted and achingly befuddled, portrays the high-school senior as the epitome of a good young man trying to figure out who he thinks he is. Though Bardwell makes a lot of first-time-out errors as a filmmaker (Dorian seems to inhabit a universe with no ambient noise), the script is remarkably observant, treating Dorian’s relationships with his macho older brother and hardliner dad with refreshing complexity.