Severe as fiery hail and blood flooding the streets, darkness gets its own day of misery in the Biblical plagues. It shrouded the land for three days like a blackout drape, resulting in an agony Exodus describes as “the location of weeping and gnashing of teeth.” The abandonment of light is one of the most enduring metaphors for estrangement, diminished perception, and the total eclipse of hope.

Justen Waterhouse has organized a three-part film series at Henry Art Gallery—a meditation on darkness in film. Waterhouse came to Seattle about six years ago from Taiwan, and became a staple in our arts community with her involvement with the Frye Art Museum and the Institute for New Connotative Action (INCA). A lover of films, she explains that “they took on a different weight for me last year. There was the arts community losing some members and stability, the political climate, the stress experienced by the community-body. It seemed like a dark time shared by everyone.” The films she selected “refract the ideas of darkness through the lens of political oppression, colonial psychology, and more.” By Waterhouse’s choices, the guidelines for what constitutes darkness seem wide. “Each film is like a mini-hell,” Waterhouse says. Appropriate, then, is Dante’s description of Hell as “solid darkness stain’d.”

The first film screened in February: Touki Bouki by Djibril Diop Mambéty, in which friends Mory and Anta, dissatisfied in Senegal, plan to leave for Paris—riddled with uncertainty, torn between national allegiance and the promise of a fantasy city. One scene in the film shows the pair riding through the grasslands of Senegal on Mory’s bullhorned-skull-mounted bike as Josephine Baker’s voice croons “Paris, Paris, Paris… it’s paradise on earth.” The film is in many ways a lesson on indecision, as towards the end, Mory is struck by his inability to board the ship to Paris.

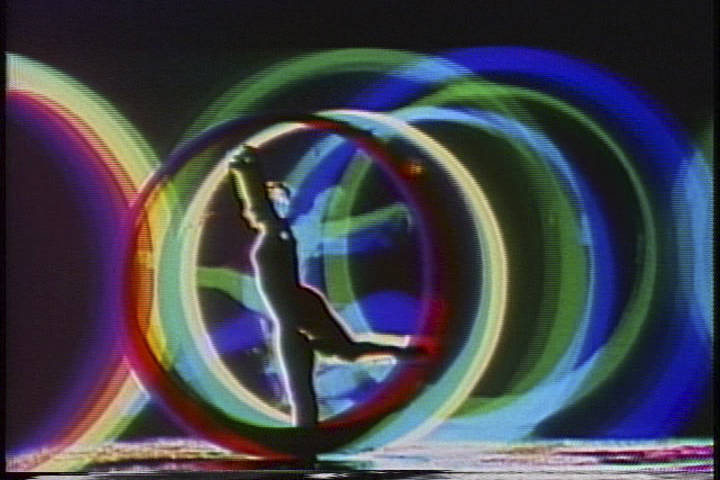

Upcoming on Thursday is Toshio Matsumoto’s Shura, a chilling Japanese experimental revenge drama. With nods to classical Japanese theater styles kabuki and noh and their use of pacing through percussion, this film takes advantage of cinematic darkness to disconcert the viewer. The cheated samurai furiously pursues his deceivers in opulent high-contrast monochrome. Moving objects threaten skulking hands that lurk behind the shadows as the samurai darts around using the labyrinthian slashes of light.

April’s feature is Sergei Parajanov’s The Color of Pomegranates, formerly known as Sayat-Nova. This nearly silent film, inspired by Armenian illuminated manuscripts, is a “poetic biography” of the Armenian poet and singer Sayat-Nova. The darkness here is offscreen and the result of censorship: After the film’s release, the Communist Party of Armenia and the USSR state film committee objected to its portrayal of Sayat-Nova, and parts were removed and re-edited by filmmaker Sergei Yutkevich. Parajanov was imprisoned by Soviet authorities a few years later for his subversive activities and kept on close watch afterward, which indelibly altered his career in cinema.

Is there an indulgence in enshrouding yourself in films about darkness, like listening to sad songs while you’re crying just to keep the pity party going? For Waterhouse, the film series is more than self-interested solace. “It’d be a mistake to come to the films and think ‘sad thing happened, watch movie, get better.’ I think it’s a different act of solidarity.” She explains that the series creates a specific situation for conversation: “The discussion I had with people after Toubi Bouki couldn’t have happened at an art show. You are silent and mostly alone through a film experience. In an art space, you enter already aware of a certain level of engagement, codified in a certain way, that is expected of you, which I think makes it hard to maintain a personal experience.” Waterhouse also offers lists of extended reading suggestions at each screenings.

Why these films right now? “They’re all uncompromising works by uncompromising directors who are evidence and a product of dark times, a darkness we may struggle to understand,” Waterhouse explains. “They were able to maintain their agency through trauma.” Her words sound similar to philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s reflection on the word “contemporary”: “The contemporary is the one whose eyes are struck by the beam of darkness that comes from his own time” as “something that concerns him.” When artists identify and encapsulate the darkness of their conditions, it gives us context and grounding beyond the constant amnesiac shock of the present. After all, when we look into the darkness long enough, we may just see tiny interstices of light. Darkness Film Series: Shura, Henry Art Gallery, 4100 15th Ave. N.E., henryart.org. Free (with online registration). All ages. 6 p.m. Thurs., March 16. film@seattleweekly.com