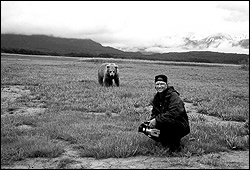

We shouldn’t be laughing at a guy who, we know at the outset of this documentary, is going to die at the end. Yet in the first few minutes of Grizzly Man (which opens Friday, Aug. 12, at the Guild 45th), a comic star is born. With his blond hair always sculpted into a Prince Valiant cut, maniacally performing for his own video camera, bear-obsessed Timothy Treadwell (1957–2003) delivers one of the funniest monologues of the year. “I may be hurt, I may be killed,” says the “kind warrior. I am like a flower. I am like a flower.” He’s more like a goofy surfer-dude public- access TV host, or a man-child character played by Martin Short or Andy Dick. Having spent 14 summers visiting Katmai National Park in Alaska as a self-appointed protector of grizzlies, he shot some 100 hours of footage of his rambling, New Age stream of consciousness—part diary, part therapy, part eco-screed, part educational tool for schoolchildren. This raw material then came into the editing hands of Werner Herzog (see interview), who also added new interviews and narration of his own. The result ranks among Herzog’s very best films; it’s surely one of the finest documentaries of the year.

There’s an immediate contrast between Treadwell’s ditsy American optimism and the German intellectual’s dry, disapproving commentary on this “primordial encounter” between man and beast, but Herzog doesn’t overdo it. Treadwell was, unquestionably, a bit of a fool—a guy warned by rangers, scientists, and native Alaskans not to get too close to the grizzlies. (“He was acting like he was dealing with people in bear costumes,” says one.) But for Herzog, he’s also a bit of a holy fool, like Kaspar Hauser. You almost can’t stand to watch his trusting approach with the wild animals (“It’s OK! You’re the boss! I love you!”), because you’re afraid he’ll get mauled on camera. It’s Fear Factor with real fear. (Only audio exists for the final, fatal attack, but we never hear it.) His behavior is so reckless, so heedless, so ingenuous that it becomes, in a sense, an act of religious faith. To risk touching your god is to risk being destroyed.

Certainly, Treadwell’s beliefs belong to the ecstatic strain of American worship—he’s like Thoreau on E, Whitman without the book learning. “Facing the lens of the camera took on the quality of a confessional,” Herzog observes. Treadwell avidly thanks the bears “for giving me a life. The miracle was animals.” He’s got the fervency of an old sinner who’s finally found redemption, and gradually, Herzog supplies the details of his former life in the lower 48—just another kid from the suburbs, a failed actor in Hollywood, drugs and alcohol. It’s harder to laugh at this stuff, nor does Herzog intend you to. (Richard Thompson’s spare, melancholy score also helps give Treadwell his dignity.)

Herzog also allows us to respond as Treadwell did to the awesome beauty of Alaska—the jagged glaciers, the long, low light of summer, the rich array of wildlife beyond “the Grizzly Maze” (a brush-and-river delta where the bears feed each summer, fattening up for hibernation). Some of the film’s most magical and playful moments come from the foxes that also live there; Treadwell clearly loves them as much as the bears, even when they steal his favorite hat. He wasn’t just doing Jackass stuff for the thrills. Though untrained as a filmmaker or as a scientist, he got some amazing shots: rain on his tent walls, flashlights waving in a storm. (Indeed, Herzog defends him as a fellow filmmaker, not as an ecologist.) There are even traces of The Blair Witch Project, as a guy raggedly documents his mission into darkness and insanity.

And, like Blair Witch, there are elements of fakery to Treadwell’s story that Herzog also finds fascinating. As part of his desire for fame (which got him on the Late Show With David Letterman), he presents himself as a lone crusader in the woods—when, in fact, his girlfriend was killed along with him. The Robinson Crusoe thing was an act, like everything else in his life, which also requires considerable egotism and self-delusion. Herzog wryly notes, “The actor in his film has taken over from the film director. I have seen this before on a film set.” Somewhere, Klaus Kinski is smiling at that.

Yet both Treadwell and Herzog are silent during one of the film’s most astonishing sequences, as two male bears wrestle for dominance on the beach. It’s like a collision between monster trucks; their might is unimaginable compared to our hairless human frailty. Never mind how Treadwell tended to anthropomorphize them and give them names, how he considered them cute, like the foxes. You realize that grizzlies are essentially sharks with fur.

This is where Herzog criticizes Treadwell’s “sentimentalized view that everything was in harmony,” as opposed to his own perception of “chaos, hostility, and murder” being the essential state of nature. Treadwell is romantic, and perhaps also messianic (the bears were already federally protected where he set up camp). He reminds you of the poor kid in John Krakauer’s Into the Wild, Chris McCandless, who starved to death in the same Alaskan wilderness that so seized his imagination. McCandless left behind a diary, and Treadwell his tapes. Neither deserved to die for his ideals, but idealism almost always has tragic consequences for Herzog.

In the end, as Herzog visits the Grizzly Maze with a few of Treadwell’s friends, you share both his skepticism of and respect for this crazed, comical outsider performance artist. Like the rest of Grizzly Man, this assembly raises the same reactions you’d have at a funeral: Sometimes you laugh; sometimes you cry.